69 Canine Infectious Diseases

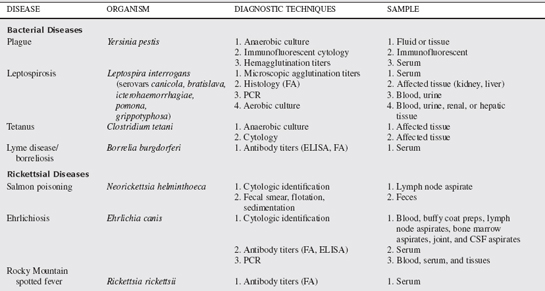

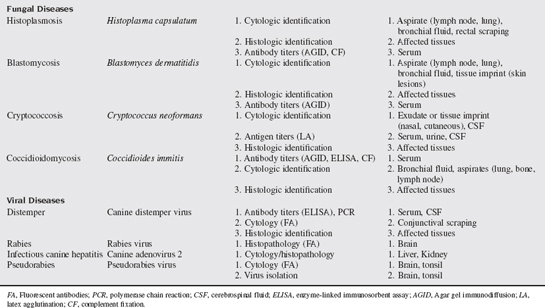

SUMMARY OF DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES

A multitude of infectious diseases are encountered in small animal veterinary practice and, as such, numerous diagnostic tests and techniques are used in their diagnosis. Some of the commonly used techniques and tests available in small animal infectious disease diagnosis are discussed in this chapter. Specific tests for the diseases discussed in this chapter are summarized in Table 69-1.

Serologic testing refers to the detection of endogenous antibodies directed against a particular infectious agent or detection of actual infectious antigens. Numerous techniques are used in this process. Serologic antigen detection is considered more diagnostic of infection than antibody detection because antibodies can be present in animals that were previously infected. Additionally, serologic antibody tests are more likely to have cross-reactivity with antibodies directed at other, closely related agents. Therefore high single antibody titers, or demonstration of a fourfold increase in serum antibody titers, are generally required to support active infection.

Conjunctival scrapings can be used for cytologic diagnosis of distemper. Scrapings are collected by first removing mucus and tears from the inferior conjunctiva with a cotton tip applicator. A heat-sterilized blunt metal spatula or dull scalpel blade is then used to repeatedly scrape the superficial layer of conjunctiva until a small amount of tissue can be lifted off, applied to a glass slide, and smeared. This usually causes erythema of the conjunctiva and a slight amount of bleeding. Slides are sent for distemper fluorescent antibody staining. Using routine in house stains, the slides can be evaluated for characteristic intracytoplasmic distemper virus inclusions.

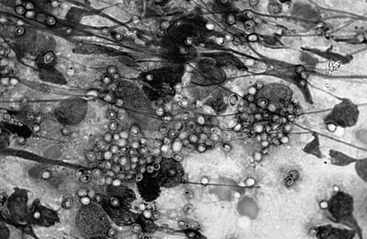

Rectal scrapings can be useful for detection of histoplasmosis (Fig. 69-1). This is performed by passing a gloved finger or cotton-tipped applicator into the rectum and scraping the mucosa repeatedly. The finger or applicator is removed and the tip lightly rolled on a slide for staining with routine in house stains.

CSF is collected in a much more refined manner and must be handled with care. Cytologic preparations are best interpreted by an experienced cytologist and made after cytocentrifugation to concentrate the low quantity of cells into a small area. The fluid must be analyzed within a short period before cellular degradation. Therefore a laboratory capable of handling CSF should be identified before collection and be reachable within 30 minutes. The atlantooccipital cistern is the most useful site of collection for most central nervous system (CNS) infections. After anesthesia has been induced and the site aseptically prepared, the dog is placed in lateral recumbency (right lateral for a right dominant person) with the neck flexed to open the atlantooccipital cistern. The space is identified as a subtle depression in the center of a triangle made by placing the left thumb on the right wing of the atlas, the left middle finger on the left wing, and the index finger on the occipital protuberance. This correlates to the cranial aspect of the atlas. A 22-gauge, 1.5- to 2.5-inch spinal needle is then slowly inserted into this space with the needle nearly 90° to the spine and directly on midline with the bevel directed cranially. It is uncommon to completely insert a 1.5-inch needle into a dog of any size. The stylet is removed intermittently to evaluate for flow so that the needle is not advanced into the cord or brain stem. If frank blood appears, the needle has been placed off midline and the needle should be removed. After CSF flows from the needle, it should be aseptically collected by allowing it to drip into an empty glass tube. Approximately 1 to 2 ml is required for most diagnostic tests. The needle is then removed. Cell counts, cytologic evaluation, and fluorescent antibody techniques can be applied to CSF for detection of canine distemper virus antigens. Titers for distemper, Ehrlichia canis, RMSF, Cryptococcus, and other infections can be determined and compared with serum concentrations for diagnosis. Fluid can be submitted for cultures.

VIRAL DISEASES

Canine Distemper

Canine distemper is caused by a single stranded RNA containing Paramyxovirus virus.

Canine distemper virus (CDV) is acquired from infective aerosol respiratory secretions.

CSF analysis in dogs with acute encephalitis usually shows increases in protein concentration and increased mononuclear cells, predominately lymphocytes. Detection of anti-CDV antibody in the CSF is the most definitive evidence of distemper encephalitis, provided that blood contamination is minimal during collection. If blood contamination is present in CSF, serum, and CSF antibody titers for CDV and canine parvovirus can be measured and their corresponding CSF to serum ratios computed. If the ratio for CDV antibodies exceeds that of parvovirus, then a diagnosis of CDV infection is plausible (see Chapter 4). Immunocytology and immunohistochemistry can be used to detect viral antigen in tissue samples. Conjunctival, tonsillar, and respiratory samples may reveal a positive fluorescence test early in the course of disease before antibody titers increase. This technique may also be applied to tissue samples obtained at the time of biopsy or necropsy.

Several different vaccines are available that provide active immunization of animals. These include modified live, inactivated whole virus, subunit products, and recombinant vector–based vaccine. Use of heterologous vaccination with measles virus can provide temporary immunity in animals younger than 6 weeks.

Postinfection immunity from canine distemper infection is reported to last at least 7 years.

Canine Adenovirus Infections

Laboratory abnormalities depend on the severity of injury to the liver, kidneys, eye, and vascular endothelium. Hemogram changes include leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. In severe infections, DIC and associated coagulation abnormalities can be observed with increases in activated partial thromboplastin time, one-stage prothrombin time, fibrin degradation products, and d-dimer concentrations.

Pseudorabies

Pseudorabies, also known as Aujeszky’s disease or mad itch, is caused by an α-herpesvirus.

Pseudorabies is found worldwide but is more common in areas with a high population of pigs.

Ptyalism was the most common clinical sign of pseudorabies in dogs and was reported in 100% of cases in one retrospective study. In the same report, all dogs had exposure to pigs. Restlessness, anorexia, ataxia, wandering aimlessly, tachypnea, dyspnea, vocalizing, and pruritus were associated with the disease in more than 50% of dogs with pseudorabies. Muscle spasms, vomiting, aggressiveness, trismus, dysphagia, and abnormal papillary light responses can also be seen. Death routinely occurs within a short period after the first clinical signs become apparent.

Rabies

Furious and paralytic forms of the disease are described in dogs. These clinical manifestations are arbitrary and are used to describe changes in the dog’s behavior during progression of the disease. The furious form of the disease in dogs is characterized by aggression to people, animals, or inanimate objects. Dogs may appear excitable, bark, or attack imaginary objects. Ataxia or incoordination precedes the more dramatic clinical neurologic signs. Seizures, coma, and paralysis are evident before the animal succumbs of the disease.