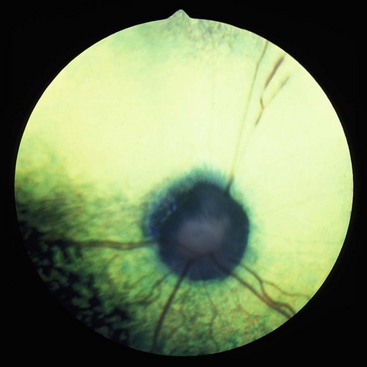

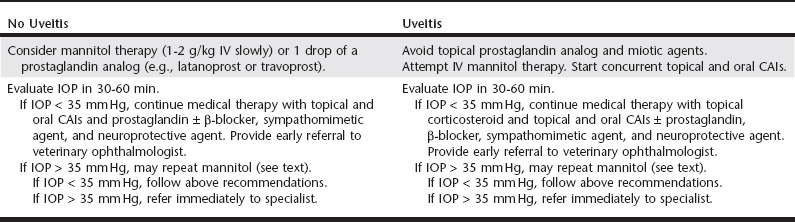

Chapter 251 Glaucoma can arise from both primary and secondary causes that are associated with increased IOP, which damages primarily the inner retina and the retinal ganglionic cells. Primary glaucoma has been observed in many breeds (Box 251-1) and is defined as an increase in IOP in the absence of concurrent ocular disease. It demonstrates a strong genetic basis with bilateral ocular involvement. Both primary open-angle and primary angle-closure glaucoma are identified in dogs. Primary angle-closure glaucoma is eight times more common than primary open-angle glaucoma in dogs. There is also a more than twofold higher frequency of primary angle-closure glaucoma in female dogs than in males. Secondary glaucoma occurs two times more frequently than primary canine glaucoma and may be related to disorders of the lens (cataract, intumescence, lens rupture or trauma, lens-induced uveitis), uveitis (see Chapter 249), hyphema, intraocular neoplasia, iridociliary cysts, misdirection of the vitreous, chronic retinal detachments, intraocular pigment dispersion or melanosis, and trauma. Clinical signs of glaucoma differ for acute and chronic glaucoma (Table 251-1). However, the IOP should be evaluated in all cases of a red eye with a dilated pupil. TABLE 251-1 Clinical Signs Observed in Acute and Chronic Glaucoma in Dogs Commonly observed ocular signs of acute glaucoma in dogs include a red eye caused by episcleral injection, squinting, diffuse corneal edema, a fixed or dilated pupil, and loss of vision to complete blindness (Figure 251-1). Fundus evaluation may demonstrate a swollen or edematous optic nerve head with or without peripapillary retinal edema or separation. Figure 251-1 Acute glaucoma in a 9-year-old basset hound with an intraocular pressure of 45 mm Hg. Note the episcleral injection, diffuse corneal edema, and dilated pupil. (Courtesy Dr. Anne Gemensky Metzler.) Clinical signs that may be observed in patients with chronic glaucoma include a red eye, corneal edema, corneal striae (caused by fractures in Descemet’s membrane), a normal to enlarged globe (the latter called buphthalmos), a midsized to dilated pupil, a subluxated to completely luxated lens, degeneration of the optic nerve head with or without cupping, and tapetal hyperreflectivity (Figures 251-2 and 251-3). Figure 251-2 Chronic glaucoma in a 10-year-old cocker spaniel. Note the buphthalmos, severe episcleral injection, diffuse corneal edema, dilated pupil, and posteriorly subluxated and cataractous lens in this blind eye. The mucoid discharge is secondary to corneal exposure and keratoconjunctivitis sicca. (Courtesy Dr. Anne Gemensky Metzler.) Figure 251-3 Fundus of a canine eye demonstrating a cupped and atrophic optic nerve secondary to chronic glaucoma. (Courtesy Dr. David Wilkie.) The diagnosis of glaucoma usually is entertained based on the classic clinical signs (red eye, corneal edema, dilated pupil, loss of vision), breed predisposition (in cases of primary glaucoma), ophthalmoscopic findings, and measurement of IOP. Gonioscopic evaluation, high-frequency ocular ultrasonography, and occasionally advanced radiologic imaging may be useful in understanding the cause and differential diagnoses. Tonometry, the measurement of the IOP, can be performed with various tonometers such as by use of an indentation instrument (Schiøtz tonometer), by applanation (Tono-Pen), and by the rebound process (TonoVet) as discussed in Chapter 242. There should not be a difference of more than 2 to 4 mm Hg between the two eyes. Gonioscopy is a procedure usually performed by a veterinary ophthalmologist in which a special lens is used to view the iridocorneal angle to classify glaucoma based on the degree of angle opening (normal, narrowed, closed, and dysplastic). High-frequency ultrasonography (35 to 50 MHz) can be used to evaluate the iridocorneal angle and ciliary cleft as well as the relationship between the iris and the anterior lens capsule. The three main therapeutic goals are maintenance of vision, control of the IOP, and maintenance of the health of the retinal ganglionic cells. Additional therapeutic considerations in subacute glaucoma are the potential to preserve vision and relief of ocular pain when vision has already been lost. Once glaucoma is diagnosed, medical therapy is instituted to lower the IOP rapidly. This includes the use of hyperosmotic agents (mannitol or glycerol), oral and topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, topical miotic agents, β-blockers, and prostaglandin analogs as well as neuroprotective agents (Table 251-2). Often multiple medications are required. TABLE 251-2 Medical Options for Treatment of Acute Glaucoma with and without Uveitis CAIs, Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors; IOP, intraocular pressure; IV, intravenous.

Canine Glaucoma

Causes and Pathogenesis

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

Structure or Feature

Acute Glaucoma

Chronic Glaucoma

Intraocular pressure

Usually elevated

Usually elevated

May be low to normal (due to ciliary body atrophy)

Conjunctiva

Episcleral injection

Episcleral injection

Cornea

Edema

± Edema

± Descemet’s striae

Globe size

Normal

Normal to enlarged (buphthalmos)

Pupil size

Dilated

Midsized to dilated

Lens

Normal position

Normal, subluxated, luxated

Optic nerve

Normal or swollen optic nerve head

Atrophied and/or cupped

Retina

Normal or peripapillary retinal elevation/edema

Tapetal hyperreflectivity, retinal vessel attenuation, choroidal infarcts

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree