20 Canine Brucellosis

Brucellosis is an infectious disease that causes pregnancy loss and infertility in dogs. The disease is uncommon in developed countries, but affected kennels are identified in the United States at least once yearly. Loss of individual animals and subsequent loss of breeding stock and income can be devastating. Canine brucellosis also can be transmitted to humans; although this occurs rarely, it can cause pregnancy loss in women. Any veterinarian that identifies brucellosis in a dog is required by law to report the diagnosis to the state department of health.

III. HISTORY AND CLINICAL SIGNS

Many dogs carrying the Brucella organism have no clinical signs of disease. Infected bitches may show no change in estrous cycling or type of vulvar discharge produced during heat. The classic clinical sign in bitches is spontaneous abortion at about day 40 to 50 of gestation. Aborted pups usually have died well before abortion, and greenish gray vulvar discharge may persist for weeks after abortion occurs. Pups may be born live but do poorly, generally dying well before weaning. In males, brucellosis causes epididymitis (see Chapter 25). Again, dogs may show no clinical signs of disease. Semen quality declines after infection, and agglutination, or clumping, of spermatozoa may be evident.

IV. DIAGNOSIS

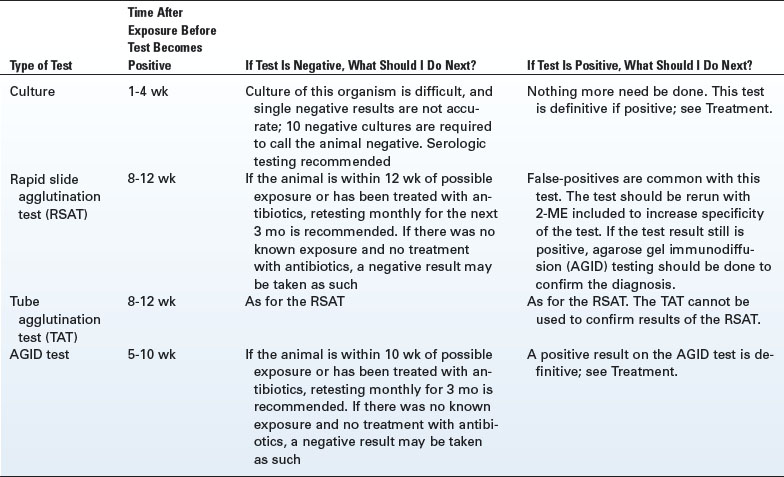

Several types of diagnostic tests are commercially available. The two broad categories are culture and serologic tests (Table 20-1).

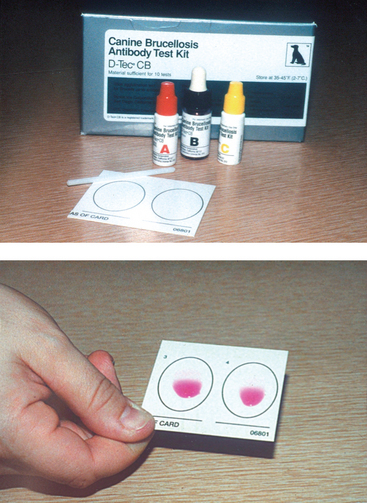

The RSAT is the test commonly performed in the veterinarian’s office (Figure 20-1). Blood is drawn from the animal to be tested and centrifuged, and the serum is drawn off. A drop of serum is placed on the test card. A drop of positive control from the test kit is placed on an adjoining circle on the test card. A drop of “agglutinating agent,” which will form clumps with antibody and is stained purple to increase the visibility of agglutination, is added to each and mixed. The card is slowly rocked back and forth, and the area where the mixture sheets down the card is observed for agglutination, comparing the test sample to the positive control. All samples begin to clump after 2 minutes. This test is very sensitive; any animal that tests negative either has not been exposed to B. canis or is in the very early stages of infection. This is not a specific test. Other bacterial organisms elicit formation of antibodies that resemble Brucella, such that false-positive results may occur. If the animal has recently been exposed to another organism and has mounted an appropriate immune response to it, that may be recognized by the RSAT. Vaccination has not been demonstrated to cause false-positive results.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree