CHAPTER 53 Candidiasis

ETIOLOGY

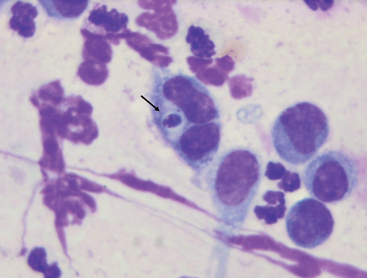

Members of the genus Candida are dimorphic fungi that belong to the family Cryptococcaceae; they are small (2-6 μm), thin-walled, ovoid yeasts that reproduce by asexual multilateral budding.1,2 They are ubiquitous, are found on many plants, and are considered part of the normal flora of the alimentary tract, upper respiratory tract, and genital mucosa of mammals. Candida species are opportunistic pathogens, and Candida albicans is by far the most common species isolated from healthy and diseased people and animals (Fig. 53-1). Other common Candida species include C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. famata.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Candida is first acquired by neonates during passage through the birth canal, subsequently colonizing the mucosal and mucocutaneous surfaces of the gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, and genitourinary tracts.1 Opportunistic infections and life-threatening pathology can occur in neonatal and adult patients whose immune defenses have been altered by disease or various interventional strategies.2

Risk factors for candidiasis include prolonged broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy;1,3–5 disruption of cutaneous or mucosal barriers by burns, surgery, cytotoxic agents, or trauma;1 prolonged immunosuppression by disease states such as sepsis;5 and administration of drugs such as glucocorticoids.1,2,4 Other risk factors identified are low birth weight5 (e.g., in premature foals), long-term placement of indwelling intravenous and urinary catheters,1,3,5 long-term endotracheal tubes,1,5 prolonged parenteral nutrition,1,3,5 persistent neutropenia,1,2 and severe primary immunodeficiency (e.g., agammaglobulinemia, selective IgM deficiency) and acquired immunodeficiency (e.g., failure of passive transfer).6

PATHOGENESIS

Under most circumstances, overgrowth of Candida spp. is inhibited by the normal microflora of the GI and respiratory tracts, genitalia, and skin. When the mammalian host is compromised by any of the previously mentioned risk factors, Candida can readily become pathogenic. Local proliferation in wounds or mucosal surfaces is often the first step in spread of infection.1 The organism often invades through breaks in the skin or mucosa; electron microscopic studies have implicated mechanical as well as enzymatic factors in the invasion of the oral epithelium.4

Once in the body, circulating neutrophils appear to be an important determinant of further spread of candidal infection.1,2,4 Immunosuppressed patients and those with persistent neutropenia are at risk for developing candidiasis.

The microcirculation of tissues (e.g., lung, kidneys, joints, eyes, liver, brain, myocardium) acts to filter and clear the blood of pathogens. When systemic candidiasis is present, this activity results in embolic colonization and microabscess formation at these sites,1 leading to the different presentations of candidal disease.

Candida albicans appears to have a number of virulence factors that promote successful parasitism, such as rapid germination upon seeding of tissue from the bloodstream, protease production to help invade tissues, surface integrin-like molecules for adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins, phenotypic switching and surface variation to avoid clearance by the immune system, and hydrophobicity.2 Candida also has several mechanisms by which it can develop resistance to several antifungals, thereby increasing its pathogenicity.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Thrush

Thrush is a local overgrowth of Candida spp. in the oral mucosa and tongue that manifests as white plaques on these areas (Fig. 53-2). Oral colonization with infection is the most common presentation in immunosuppressed human patients, especially those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. This is likely the most common presentation in horses as well, although epidemiologic studies are lacking.8 Mucocutaneous forms of candidiasis such as thrush are often related to defects in cell-mediated immunity, whereas systemic spread is generally associated with neutropenia.2 Oral candidiasis is a clear indication for initiation of antifungal therapy and pursuit of further diagnostic testing to determine systemic involvement.

Systemic Candidiasis

Clinical manifestations of systemic candidiasis are often nonspecific, with unresolved fever the only clinical sign in many cases.9 Hematogenous candidiasis can occur after colonization of the oral mucosa or GI tract or can be acquired through the introduction of venous (and urinary) catheters. Administration of total parenteral nutrition is a risk factor for human patients, and this association appears likely in the foal.1,3,5,8

The hematogenous spread of Candida can lead to meningitis, omphalophlebitis,5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree