12 Bite Injuries

Introduction

Some of the features that help decide which species may have inflicted the injuries are common sense. For example, the relative sizes of the predator and the victim are important. Thus, it would be extremely unlikely that a European otter would attack a Texel ram by biting it over the shoulder blades. Distribution of puncture marks may also give clues to the attacker. Cats commonly kill by biting the neck and head to immobilise the prey quickly and prevent struggling. This is particularly true if the victim is relatively large. Stoats show similar tactics when killing birds, chicks being wounded over the sternum and furculum (wishbone) whereas bigger birds are bitten on the head and neck.1 Dogs, however, bite whatever they can.

Other useful clues to predator type include estimates of the size of the mouth, calculated by measuring the intercanine distance of ‘bite pairs’. This is straightforward if the investigation requires a distinction to be made between a ferret and a Doberman pinscher. It is less easy if there is an overlap in jaw size, as occurs, for example, with a ferret to a young cat.1

Dog-bite injuries

Hares

In a series of 53 hares examined by the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW),2 79% suffered abdominal injury, 77% had chest injury and 74% damage to the hind limbs. Research commissioned by the Hunting with Dogs Inquiry in England showed somewhat similar results with 75% of hares with chest injuries, 41% with abdominal damage and 58% with significant bites to the hind limbs.3

Chest injuries

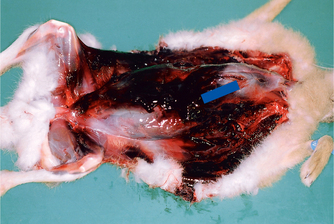

Chest injuries consist of fractures of multiple ribs, irregular holes in the chest wall (Fig. 12.1) (often associated with the fractured ends of ribs), emphysema in the chest wall, puncture wounds and laceration of the lungs, haemothorax and, occasionally, puncture wounds to the heart. The sternum and the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae may be fractured during these attacks. These major thoracic injuries are accompanied by extensive subcutaneous and intramuscular haemorrhage over the chest walls, shoulder and back (Fig. 12.2).

Other injuries

Subcutaneous and intramuscular haemorrhages are regular features in the hind limbs but fractures of the long bones are uncommon. Other injuries include fractures of the scapula, fracture–dislocations of the lumbar or thoracic spine, and crush damage to the lumbar vertebrae and pelvis. Serious head injuries appear to be infrequent. Fracture or dislocation of the neck can occur during dog attack but are more commonly inflicted by the handler after picking up a non-fatally wounded hare.

Doubts have frequently been raised over the diagnosis of ‘biting injury’ in the absence of holes in the skin, not only in hares but also in other animals. From a lay viewpoint this is understandable. However, the forensic veterinarian should make it clear that puncture wounds in the skin are not an essential element of dog-bite injury. The same is true for badger bites of smaller creatures where fatal crush injuries to the chest are caused by single, well directed bites over the back and thorax.4

Differentiation of the injuries sustained by hares attacked by dogs from those arising in motor vehicle accidents relies on the same diagnostic pointers that are valuable in the investigation of the cause of injuries to dogs and cats (see Chapter 3: Non-accidental injury). The absence of oil and grease marks, abrasions, head injuries or long bone fractures, when combined with the pattern of the injuries described above, should leave little doubt as to the cause.

Deer

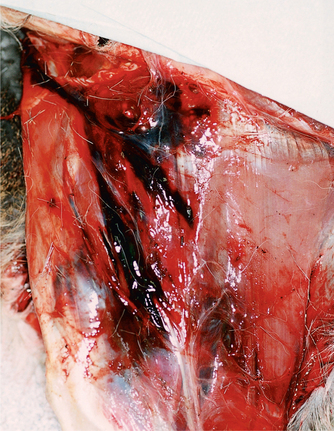

In contrast to the situation in hares, where puncturing of the skin by dog bites is frequently absent, irregular tears and punctures in the skin over the posterior aspects of the hind limbs and the ischium are commonly found in deer subject to dog attack. These skin lesions, although obvious, may appear relatively minor (Fig. 12.3) and, as such, pose a danger for the unwary pathologist because they may belie the severity of the underlying lesions. The bites can cause extensive laceration of muscle (Fig. 12.4) and severe subcutaneous and intramuscular haemorrhage. Violent struggling as the deer attempts to escape may compound the injuries, resulting in extensive tearing of the adductor muscles of both hind limbs. Similar damage can occur over the lumbar region.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree