Pre-purchase veterinary advice can help clients to have more realistic expectations and better owner–animal relationships (Kidd et al. 1992; Serpell 1996), and evidence (e.g. Patronek et al. 1996; New et al. 2000; Scarlett et al. 2002) also suggests such advice may make it less likely the owner will relinquish the animal into rescue shelters (Figure 6.1). Veterinary professionals may also reduce relinquishment by suggesting people rehome pets rather than buy deliberately bred animals and advising neutering to prevent animals being bred for whom there are not available good homes.

This advice can spread as further contagion. Owners may discuss matters with fellow animal purchasers (e.g. other people looking to buy a puppy or to set up a hobby farm). Purchases may lead to trends where people follow their peers (and buy status, fashion or designer pets), or copy their parents (and buy the breeds with which they were brought up). Breeders and dealers may respond to consumer demand for animals who are set up for better lives (e.g. by being socialised or already in a bonded pair). Changing owners’ decisions can therefore have much wider ripple effects on future purchasers.

Figure 6.2 Waiting room noticeboards can inform and direct owners to improve animals’ welfare. (Courtesy of SPCA Hong Kong.)

Clinics who want to give this advice may need to be proactive about getting owners into the surgery to discuss issues. Most practices can think of effective methods (advertising, special offers, etc.) and the benefits (increased footfall, future bonded clients, etc.), but may also be concerned with the perceived barriers. Practices can minimise potential barriers such as staffing costs, for example by scheduling pre-purchase consults on afternoons when staff are otherwise less busy; charging pre-purchase consultation fees, which are reimbursed if the clients come to you for their first vaccination; or include free pre-purchase advice within an overall (cradle-to-the-grave) health package. Plus, giving such advice can save time overall by preventing the need for later (usually long and uncharged) discussions of behavioural problems.

We can help other animals by being general animal welfare ambassadors to our clients. This uses our direct personal contact with many people and our status as key opinion leaders on animal welfare issues. Waiting room noticeboards can advertise only breeders who the practice knows are responsible (e.g. who come to the practice to obtain the appropriate health tests) and trainers the practice knows use appropriate methods (e.g. are registered with a recommended body, avoid aversive training or still propagating dominance-based theories). Noticeboards can also provide targeted welfare advice (Figure 6.2). This leadership can be especially contagious when veterinary professionals advise clients who are also key opinion leaders, such as prominent farmers, breeders, trainers or celebrities.

This advocacy can go beyond the species we treat. Farm animal practitioners can advise farmers about the welfare of other animals (e.g. their sheepdogs). Small animal practitioners can advise pet owners about the welfare of animals that produce their food, and encourage owners to purchase higher welfare farm products. Many clients do not understand farming and distance themselves from thinking about it (Frewer & Salter 2002; McEarchern & Schroeder 2002), so we can help to inform, remind and inspire people about farm animal welfare. Opportunities are surprisingly common. For example, we can mention welfare issues in discussions about bland diets (e.g. chicken) or training (e.g. sausages and other treats). Some practices even put posters or leaflets in the waiting room. Our knowledge of client decision-making, and our experience in delivering complex scientific information to laypeople, can help us to deliver messages appropriately and tailor them to each client. For example, rather than explaining the complexities of Chapters 1, 3 and 4, we can instead advise on small steps owners can feasibly implement, such as using only certain shops. Where we feel we lack this knowledge, our professional bodies or trustworthy charities can provide accessible resources we can adapt.

6.2 Beyond Clients

We may also want to act as animal welfare ambassadors to non-clients. Veterinary professionals are especially well placed to do this. We are experienced at communicating problems in understandable, non-emotive language. We have credibility and authority as key opinion leaders, so our letters or emails can carry significant weight. We can also often provide practical solutions to make the messages more constructive and effective.

Veterinary practices can forge relationships with other local key opinion formers such as foot-trimmers, nutritionists, artificial insemination technicians, breeders, trainers, riding schools and instructors, racetracks, groomers, boarding kennels and shops. For example, collaborating with pet shops can allow you to educate staff on how to care for stock and advise pet purchasers, perhaps providing jointly branded advice leaflets with your logo and address. We can also write to retailers (e.g. pet shops or grocers), businesses (e.g. zoological gardens), local authorities and politicians about issues of concern.

Some motivated practices also do local charity work, such as free health checks or microchipping (Figure 6.3). These can act as advertising and increase footfall, and can be easy to organise by linking them to national programmes which provide literature, administrative and media support. Other practices put on community events or visit local groups such as schools, children’s clubs and learned societies.

Veterinary professionals can highlight welfare messages through the local media (e.g. local newspapers and radio), social media (e.g. blogging or networking sites) or specialist media (e.g. farming or equine magazines). We can report individual cases (e.g. a stick injury), case series (e.g. an increased incidence of digital dermatitis) or general issues (e.g. biosecurity). Good cases may be those that are unusual, topical, human and relevant to the audience – news stories are not always about scandal, celebrity and money – and which come with good pictures and personal quotations. Good cases should also relate to animal welfare issues that readers can do something to prevent (e.g. parvovirus or fishing-line injuries). For example, some cases highlight the harmfulness of common practices such as fireworks and balloon races (Figure 6.4). Media work can provide free marketing, improve the practice’s reputation for compassion, be enjoyable, improve morale, reduce future frustrations and provide excellent opportunities for welfare offsetting. The risk of being misquoted or misreported is actually a very low risk because reporters want to maintain good relationships and obtain heart-warming stories. Some practices add value by scheduling perennial stories (e.g. firework fears) and running competitions asking readers to vote for their favourite story.

Figure 6.3 Welfare-focused practices can do local charity work such as free microchipping.

(Courtesy of SPCA Hong Kong.)

6.3 Professional Cooperation

Another way to achieve welfare improvements is for local practices to work together. Cooperation can take three forms: coordination, communication and collaboration. Welfare standards can be contagious within the profession as much as they are in the wider society.

Figure 6.4 Good stories are often topical and have a real welfare message, such as highlighting the dangers of balloon races.(Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Coordination involves practices cooperating to harmonise their work to best improve animal welfare. For example, if local practices agree not to provide a particular overtreatment (e.g. bulldog caesarians without neutering), owners will not have the option of selecting different practices without travelling long distances – so practices avoid the race to the bottom driven by non-cooperative competition.

Even where coordination is not possible due to legal barriers or inter-practice politics, there is still benefit to better inter-practice communication about welfare-relevant issues, cases and practice policies. Such communication can mutually educate each practice with fresh and outside ideas and solutions, and knowing what other practices do can help to decide whether tactical overtreatment is appropriate.

Even better is where practices enter into collaboration to work together on an issue. Practices might share stock that is rarely used but urgently needed or expensive equipment and facilities. Others may collaborate on specific projects, such as obtaining and storing blood banks or donor registers, organising continuing professional development sessions on animal welfare topics or staging joint community events.

Cooperation can also be beneficial at the level of the whole profession. This cooperation can also involve communication, coordination and collaboration, through both regulatory and membership-based professional bodies.

Communication within the profession can help to discuss ideas and disseminate information. It can help people to identify priorities and share new or good practices. It can also help veterinary professionals to give each other an idea of the prevalent social norms, which they can use as a benchmark in their decision-making.

Coordination within the profession can harmonise and organise practices on a national scale. Many countries have codes of practice or deontologies that describe veterinary professional responsibilities, enforced by regulatory and disciplinary committees that can remove a professional’s licence to practise. These may describe general principles or specific duties, such as prohibiting certain interventions or specifying conditions under which interventions may be performed (e.g. that kidney transplants may be performed only by specialist teams). Countries can also set practice standards, enforced through inspection and accreditation, to promote higher standards of care.

Professional regulation can help to address issues that create difficult dilemmas for individual veterinary practitioners. Banning the routine prescription of coccidiostats means the only option is for farmers to improve their husbandry. Banning feline declawing and canine vocal cord resection means owners cannot purchase an animal and then force the veterinary professional to choose between obliging the client or euthanasing the animal. Banning killing animals without a reasonable reason could mean owners do not see their animals as disposable. Banning overtreatment means owners cannot go to a less scrupulous practice. These rules would cause welfare problems until owners realise that the easy option is prohibited, but they can have beneficial effects in the long term. Where dilemmas continue, professional regulation can also mandate welfare offsetting in certain situations (such as reporting conformation-altering surgeries).

We are often reluctant for professional bodies to have any power over our clinical decisions. However, in some cases we might welcome professional regulation. Sometimes not having one option can empower us not to provide (or offer) welfare-unfriendly options, by providing an argument to clients (that we are not allowed), reducing perceived legal risks (as a legal defence for not doing something) and reducing the pressure to provide a treatment competitors provide (by preventing them from doing so). Even where restrictions of clinical autonomy do restrict the beneficial use of a treatment, this restriction may often be worth the benefit of restricting misuse, so restrictions may be beneficial overall even if some cases would benefit from an option being permitted. For example, banning congenital hernia repair without neutering could mean some breeders choose not to get the operation done, but this ban could also help to prevent hereditary problems being passed on. Similarly, banning electronic shock collars (ESCs) may be beneficial even if they are useful in some cases.

Alternatively, professional bodies can provide guidelines that, like standard operating procedures (SOPs), can be recommendations which allow practitioners to deviate in exceptional cases (but need to be prepared to defend that deviation). Another solution is to create clinical ethics committees, either nationally or in each university or practice, which could review specific cases similar to equivalent systems that are increasingly common in human hospitals and animal research institutions. A more general approach is for codes to mandate very general duties that can be interpreted by disciplinary committees. This would allow regulatory bodies to make general rules such as prohibiting overtreatment or requiring that practitioners provide reasonable emergency treatment.

Many countries also have veterinary oaths that graduates swear on entering the profession. Professional codes and oaths often focus on duties to colleagues and clients, based on the old rationales for the veterinary profession described in Section 1.2, but it is important that they are increasingly based on what is best for animal welfare. For example, the American Veterinary Medical Association has recently updated its oath to include a stronger animal welfare commitment. These promises are usually taken to prescribe how veterinary professionals behave in their work, but oaths should not only apply from 8 am to 7 pm – a promise to make animal welfare one’s main consideration should apply to one’s whole life.

6.4 Professional Collaboration

We can also collaborate as a profession. As a profession, we have a greater capacity to work on the bigger picture than we do individually or locally. Professional bodies may have greater power to lobby governments, to engage industries, to fund or coordinate research to contribute to the media. They also can draw on the authority and trust individual members of society have for individual members of the profession, so that the professional bodies are a credible community leader on a national or international level. Professional bodies (and their officers) have their own animal welfare accounts. Professional collaboration also helps its members by helping us fulfil our claims that we are welfare experts and animal advocates, and ensuring that we remain centrally involved in animal welfare issues.

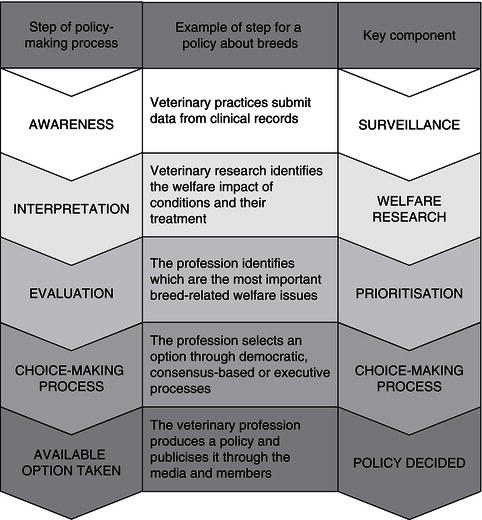

Professional bodies need to make decisions, and this can draw on the same principles as our clinical decision-making. In both cases, we need to be welfare-focused, we need to be reflective and effective, we need to realistically consider the constraints and barriers, we need to engage the relevant people and we need to use knowledge, empathy and reasoning. The processes are also similar. Professional bodies need to make assessments and decisions, and these involve a similar five steps (Figure 6.5).

Steps 1 to 3 lead to an assessment of welfare issues. This can be a position statement that informs or advises members or other people. These positions can assess situations and highlight the importance of welfare problems, or they can evaluate the options that are available. They are equivalent to evaluations in clinical decision-making and involve similar steps.

Step 1 involves identifying issues. Sometimes this is done by our members, and we can feed into our professional bodies’ decision-making processes. In other cases, issues are highlighted by public concern, such as when a law is being discussed or an issue hits the media. Steps 2 and 3 involve interpretation and evaluation. As for clinical assessments, these need to utilise both science and our experiences. We need to utilise science in our decisions wherever possible, because of its importance in resolving reaching objective assessments.

The veterinary profession is also well placed to make decisions where scientific proof is lacking. Other bodies have a difficult choice about what to do when science is lacking. They can remain silent unless there is sufficient evidence, but risk seeming weak, indecisive, dishonest or disingenuous (e.g. using the lack of science to delay decisions or maintain the status quo). Alternatively, they can make bold statements without evidence, but risk being criticised for being unreliable and unobjective. We can avoid both risks because our clinical training hones our skills at making assessments even without directly applicable science. Our professional bodies can draw on members’ practical experience and general understanding of biology (Figure 6.6), and thus avoid inactivity when there is a lack of data. For example, many practitioners are situated in the context of the issue, who thereby see welfare problems and interventions first-hand.

As well as situated practitioners’ views, our professional bodies’ position-making should draw on the expert knowledge of the specialists within our profession. While veterinary professionals can be considered animal welfare experts relative to the public, there are animal welfare specialists within the profession with an even greater degree of specific knowledge and experience. Veterinary animal welfare experts can be more easily identified since the recent establishment of a European College of Animal Welfare and Behavioural Medicine. There are also animal welfare experts outside the profession. The opinions of these experts can – and often should – carry greater weight than those of non-specialists. Just as we respect the opinions of specialists in medicine and immunology when making policies about vaccination, so can more respect be afforded to the views of those with a proven animal welfare specialisation, who devote considerable time, effort and learning to the subject of animal welfare. Nevertheless, welfare experts’ opinions should be based on building blocks of information provided by situated practitioners, even if the welfare experts make the overall assessment.

Figure 6.6 Veterinary professionals can draw on their wide general knowledge of animals’ biology. (Courtesy of Royal Veterinary College, Hong Kong Ltd.)

Steps 4 and 5 lead to a recommendation for action on the part of the professional body itself. This can be a policy, which is something the professional body intends to do. Some policies may be internally focused, such as where to buy food for catering or how to regulate members. Others may be externally focused, such as how to drive legislative or societal change. These policies then need to be converted into actions, in order to achieve animal welfare improvements. Step 5 involves actually fulfilling those intentions. Our policies need to be effective. Sometimes, this means we need to balance idealism and realism. We may need to suggest small steps that help take society on a journey.

6.5 Professional Barriers and Biases

As for clinical decision-making, we need to minimise and avoid potential problems in each step of professional bodies’ policy-making. In Step 1, we may identify issues inappropriately. We may focus on issues only reactively when they are topical in the news or subject to government consultations. Reactive work helps us maintain our reputation as a source of opinion on welfare issues. Similarly, issues raised by our members can be unavoidably skewed; for example, situated practitioners may see some issues more commonly (e.g. those that require veterinary interventions) but not others (e.g. mutilations we authorise but do not perform). Ideally, issues for consideration should be raised by more objective methods, based on welfare surveillance, as discussed in Section 6.6.

During Step 2, we may misinterpret issues for several reasons. Decisions may be made by a minority of us who happen to sit on relevant councils or committees, who may be non-practising (and therefore less exposed) or less recently graduated (and perhaps therefore less up to date). Decisions made by situated practitioners can also be biased due to our habituation or hardening to things we see or perform regularly (e.g. to breed-related conditions, systemic on-farm problems or post-operative pain). For some subjects, most veterinary professionals have not had the opportunity (or time) to consider in depth. For example, the average veterinary professional may have limited knowledge about cephalopods’ neural system, cognitive capabilities or capacity to feel pain. More objective interpretations can be based on scientific information, although an overreliance on science may make us overly conservative. One solution is to obtain evidence through veterinary animal welfare research, as discussed in Section 6.7. Another solution is to use our expert opinion within the profession, for example in an expert animal welfare committee.

In Step 3, our professional bodies may risk inaccurate evaluations. Importantly, we may inappropriately transfer our clinical assessments concerning individual cases to our wider assessments concerning the big-picture. As practitioners, we must consider the wider economic and legal situations as unchangeable constraints. As professional bodies, we must also consider whether these constraints can be changed by wider action. For example, practitioners may assess ESCs as being beneficial for some pets, but this does not entail that allowing ESCs is beneficial on a national level if banning ESCs would help more animals than it would harm (e.g. if ESCs are frequently used on many animals inappropriately) or if a ban would lead to other progressive changes (e.g. better fencing or use of more positive training methods). Professional bodies can avoid these dangers by giving more sophisticated and conditional answers. For example, we can conclude that a mutilation should be allowed if current intensive farming methods are allowed to continue, but that it would be better if sufficient support were given to improving general husbandry standards.

Table 6.1 Key principles for veterinary policy-making and their effect on proactivity.

| Principles that may promote inactivity | Principles that may promote proactivity |

| Consistency Focus Neutrality Practicality Reliability Idealism | Integrity Forthrightness Meaningfulness Progressive |

When choosing what they are going to do in Step 4, professional bodies’ policy-making has to balance a number of different values and we may excessively focus on some more than others. For example, some values can drive us towards proactivity, others towards inactivity or reactivity (Table 6.1). For example, a desire to maintain our reliability makes us wary of saying anything that might be challenged as incorrect or biased, which may bias us towards providing only conservative statements (or none at all). At the same time, such reticence can open professional bodies (and especially their officers) to criticism. For example, inactivity can make us seem complicit in the status quo (Waldau 2011), especially if we remain silent while claiming to be advocates. We need to combine practice advocacy with a solid basis – but it is a challenge to judge how proactive and how solid.

Finally, in Step 5, another potential barrier for professional bodies – as for practitioners – is its limited resources. Researching, debating and achieving welfare improvements take time and effort, and trying to do too much can risk the profession spreading its resources too thinly or weakening the impact of key messages. There are three main solutions to this.

The first is to use the members. In many professional bodies, only a relatively small percentage of members are actively involved, and most have a limited number of staff. But they have larger numbers of members who, if they are provided with information and engaged, can act as vectors and pass on contagious messages using the personal relationships they have with their clients. This makes veterinary welfare education especially important, as discussed in Section 6.8. As individual members, we can also help our professional body to develop and propagate animal welfare positions and policies. Where members are needed to fulfil policies, it is important for us to aim for a professional consensus. Like achieving concordance, this requires engaging members, good communication and open discussions. Consensus can also be built up from agreed building blocks, for example agreeing to focus on animals’ feelings, and on what policy-making processes to use, such as specific assessment methods, Delphi processes, elected officers or appointed expert committees.

The second is for us to collaborate with other welfare-focused bodies, such as industry partners, charities, government and non-governmental organisations. In some cases, these other bodies may have the resources but not the authority, so collaboration can be a valuable partnership. One recent success story is the banning of wild bird importation into the European Union, which involved a collaboration between the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the RSPCA, the World Parrot Trust, the British Veterinary Association, the Federation of Veterinarians in Europe, alongside other charities and medical experts.

The third is to prioritise our resources. Table 6.2 gives some factors by which bodies should prioritise (which could be evaluated qualitatively or quantitatively). We can focus on the most important animal welfare issues and those we can do most about. We can also focus on specifically veterinary responsibilities and accountabilities, or those where improvements can avoid members’ welfare dilemmas or offset members’ welfare harms. For example, veterinary professional bodies may focus on the avoidance of breed-related conditions that are propagated by veterinary practice, or on the employment of the 3Rs (replacement, refinement and reduction) in the use of animals for toxicology testing of veterinary medicines.

All of these steps need to be combined into one process. An example is given for tackling broiler breeder issues in Table 6.3.

6.6 Veterinary Welfare Surveillance

As for clinical decision-making, policy-making requires an assessment of the welfare issues. Firstly, the profession needs to identify issues through welfare surveillance, such as epidemiological research or widespread audit of welfare issues. Welfare surveillance is equivalent to screening for individual cases, insofar as it demonstrates the extent of welfare issues without interpreting what they mean for the animals. As for individual cases, surveillance can also screen for side effects when policies are implemented. In addition, data can highlight a problem through the media and to politicians.

Welfare surveillance can survey the prevalence of causes and symptoms of welfare problems. These need not only focus on infectious pathological causes, but could also focus on behavioural issues (e.g. Bradshaw et al. 2002; Blackwell et al. 2005) or anthropogenic causes such as fishing-line injuries (Figure 6.7). Welfare surveillance can also look for population-level indicators, such as the extent of owners’ knowledge about how to care for their animal (e.g. PDSA 2011) or the number and nature of state veterinary inspections (e.g. RSPCA 2008). Further research can investigate the causes of those causes, such as epidemiological analysis to determine disease risk factors or sociological research to examine human behaviours, for example looking at the best ways to communicate information about welfare issues (e.g. Yeates et al. 2011). Surveys can examine how severe welfare issues are perceived to be by veterinary professionals (e.g. Yeates and Main 2011a).

Table 6.2 Factors for professional bodies to consider when prioritising issues/actions.

| Factor | Examples |

| Animal welfare importance | Intensity for animals affected (average and range) |

| Duration and frequency for animals affected (average and range) | |

| Numbers of animals affected | |

| Confidence in knowledge about the issue | |

| External effects | Effects on other animals |

| Effects on humans | |

| Effects on the environment | |

| Responsibility | The extent to which the welfare issue was caused by humans |

| The extent to which the welfare issue was caused by veterinary professionals (offsetting) | |

| The extent to which the veterinary profession has a moral responsibility for those animals | |

| The extent to which the veterinary profession has a legal responsibility for those animals | |

| Exigency | Relative urgency of the issue (i.e. does something need doing now or can it wait) |

| Benefits to the profession | Direct benefits to the profession (e.g. financial) |

| Indirect benefits to the profession (e.g. political, image) | |

| Likelihood action will facilitate further action in the future | |

| Importance for professional body’s members | Importance to members (demonstrated by input into professional policy-making) |

| Direct benefits to the profession in achieving members’ welfare goals | |

| Direct benefits to the profession in avoiding dilemmas | |

| Indirect benefits to the profession (e.g. financial benefits or increased respect) | |

| Indirect costs to members (e.g. loss of revenue) | |

| Barriers for the profession | Direct costs to the profession (e.g. time, resources) |

| Indirect costs to the profession (e.g. reputation) | |

| Opportunity costs of doing something about it (in terms of weakening ability to do something about other issues) | |

| Actions and responsibilities of other parties | Likelihood other people will achieve the changes instead and/or better unassisted |

| Long-term benefits in cooperation (e.g. political) | |

| Feasibility of tackling the problem | Ability of the profession to perform desired action |

| Probability of action having an effect | |

| Extent of effect in reducing severity, duration, frequency and numbers | |

| Procedural elements | Representation of members’ inputs through the body’s decision-making processes |

Table 6.3 How the veterinary profession might help tackle broiler breeder welfare.

| Step, activity and outcome | Examples |

| Step 1 | Identify welfare issues – surveillance |

| Utilise existing research to identify issues | Growth rate has increased significantly through breeding (Havenstein et al. 2003) Effect of selection for fast growth on anatomy and physiology of broilers (Bessei 2006) Feed restriction of breeders, e.g. from 14 weeks (Hocking et al. 1989) Quantitative restriction, e.g. 20–25% of ad lib intake (Mench 2002), increasing towards peak lay (Hocking 1996) Some breeders fed every other day (Mench 1988) Other breeds may require less or no feed restriction (Whitehead et al. 1987) |

| Carry out surveillance through veterinary practitioners | Qualitative survey to ask broiler-industry-situated practitioners qualitative perceptions Quantitative retrospective study using broiler-industry-situated practitioners’ clinical notes Quantitative prospective study with broiler-industry-situated practitioners’ recording findings |

| Outcome: List of issues | Broiler breeder starvation, de-beaking, dubbing, lameness, etc. |

| Step 2 | Interpret welfare issues |

| Collect available scientific research that may help assess the issues identified | Relate dietary restriction to quality, quantity and behavioural needs (Kasanen et al. 2010) Identify link of starvation to frustration-behaviours, e.g. spot-pecking stereotypies, polydipsia and voracious feeding (Koštál et al. 1992; Savory et al. 1992, 1993a,b, Hocking 1993, 1996, Savory and Maros 1993, Hocking, et al. 2001) Feed restriction associated with elevated cortisol (Maxwell et al. 1990, 1992; Hocking et al. 1993, 1996, 2001; Savory and Maros 1993, Savory et al. 1993a,b) Ad lib feeding can lead to vaginal prolapse, heart failure and lameness (Savory et al. 1993b), increased aggression (Millman & Duncan 2000), and decreased immune function (O’sullivan et al. 1991; Hocking et al. 1996) Feed restriction associated with higher mortality (Hocking et al. 2002) Motivation to feed may vary between individuals (Savory et al. 1993a, Savory & Mann 1999; Savory & Lariviere 2000) Lame broiler chickens self-select analgesic (Danbury et al. 2000) |

| Collect scientists’ interpretations | Overall assessments of welfare issue (Julian 2005; Renema et al. 2007; SCAHAW 2000) Stereotypies may represent coping methods (Koštál et al. 1992; Savory et al. 1992, 1993b) Ad lib feeding leads to worse biological function (Hocking et al. 1993, 1996, 2001) |

| Commission or conduct research | Preference studies about how broiler breeders choose between hunger and pain |

| Use expert opinion | Broiler-industry-situated and poultry specialists consider higher egg-production better welfare Animal welfare specialists conclude:

|

| Outcome: Interpretation of issues | Conclude that broiler breeders suffer hunger or pain |

| Step 3 | Evaluation |

| Use scientific data | Allowing animals to forage may reduce the negative hunger experiences (Robert et al. 1997; De Leeuw & Ekkel 2004) Signs of frustration occur on all feeding methods (Savory et al. 1996; Savory & Lariviere 2000; de Jong et al. 2005; Hocking 2006) Announcing food, to allow anticipation, may improve animal welfare (de Jonge et al. 2008) |

| Use scientists’ evaluations | Where welfare is maximised at around 60% of ad lib intake (Hocking 2004) |

| Use other bodies’ evaluations | EFSA reports (Decuypere et al. 2006) |

| Outcome: Produce position statement | Produce position statement |

| Step 4 | Choice-making |

| Utilise others’ suggestions Determine foundational building blocks Determine policymaking process | Apply/adapt published opinions (eg Brillard 2001) Concern for broiler breeders’ feelings Using expert committee |

| Outcome: Produce policy | Produce policy |

| Step 5 | Achieve policy |

| Prioritise issues Collaboration Use members Prioritise methods | e.g. to focus on broiler breeders instead of fish, parasites, etc. Consider working with other bodies Consider empowering members with advice to write to local retailers, press and politicians Decide most effective method to effect change |

| Outcome: Activity | Implement priority actions |

Figure 6.7 Veterinary welfare surveillance can survey issues caused by human practices such as fishing-line injuries to non-target species. (Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree