Chapter 5 Behavior counseling and behavioral diagnostics

Causes of behavior problems

Knowledge of medicine, health, and pathology provides an important dimension for the veterinarian working with companion animal behavior problems. Prior to performing the actual behavioral consultation, it is critical that a thorough physical examination with appropriate diagnostic testing be done to rule out underlying medical conditions. For example, using behavioral modification alone for a cat with housesoiling is counterproductive if there is a urinary tract disorder or diabetes mellitus. The various categories of medical conditions that might lead to behavioral signs are discussed in Chapter 6.

Presenting signs may arise as a result of a disease process, primary behavior problems, or some combination of these factors. Signalment should be considered when determining which medical problems could be contributing to the behavioral signs. Congenital conditions might be more common in young pets, while a range of medical problems, including endocrinopathies, arthritis, alterations in the immune response, sensory decline, neoplasia, and age-related organ dysfunction (including brain aging), are more common with increasing age.1,2 Medical conditions in senior pets and their potential effects on behavior are discussed in Chapters 6 and 13.

Preparation before the session

The behavior data sheet questions should explore a wide variety of pertinent information. You can design your own forms using the outline in Table 5.1 as a guideline/ checklist (form 18 printable from web), or you can use the forms that accompany this book (see Appendix C, form C.5, client form #3, printable version available online) and 2 more comprehensive questionnaires, one for dog cases (form 19) and one for cat cases (form 20) which have not been printed within the text but are available as printable version online. There are many other such forms available for this purpose, including those at www.sabs.com.au, westwoodanimalhospital.com and www.northtorontovets.com. If you design your own forms, be certain to include questions that address all aspects of the pet’s health and behavior, since the primary complaint may be only one sign of a more complex health or behavioral problem.

Table 5.1 Basic information checklist for history collection – This can be used as a guide for history collection (printable form 18 from web)

| Family information | • Home, apartment |

| • Rural, urban | |

| • Family size, ages, schedules | |

| • Physical/mental challenges or limitations | |

| • Experience with pets | |

| • Other pets in the home | |

| Pet information | • Signalment |

| • Age at adoption | |

| • Source of pet, when obtained, previous owner information if known, why it was adopted | |

| • Personality, temperament | |

| • Medical history (medications administered, any recent or pertinent laboratory tests) | |

| • Medical/behavioral information about parents, siblings, or littermates | |

| • Diet, including type of food and frequency, treats fed, who feeds, behavior around food | |

| Training | • Methods used |

| • Types of training tools used | |

| • Confinement training | |

| • Reward use and the pet’s response | |

| • Punishment use and the pet’s response | |

| • Training methods and results | |

| • Use of behavior modification devices (and pet’s response) | |

| • Use of control devices (e.g., head halter) and pet’s response | |

| Pet’s environment, lifestyle, and daily schedule | • Pet’s housing, where it stays during the day, night, and when the family is gone |

| • Elimination areas, feeding areas, scratching or play areas | |

| • Access to outdoors through pet door | |

| • Play and exercise routines | |

| • Favorite toys | |

| • When and how long it is left alone | |

| • Time indoors and outdoors | |

| • Family members who care for the pet | |

| Reactions to people and animals | • Family members |

| • Unfamiliar people | |

| • Other pets in the household | |

| • Unfamiliar animals | |

| • How does the pet react to other animals and nonfamily members on property and off property? | |

| • Social postures, vocalizations, interactions, approach behaviors, fear, aggression | |

| Response to handling | • Bathing, nail trimming, grooming, petting |

| Primary problem | • 5 Ws: |

| 1. What happens? | |

| 2. Where does it happen? | |

| 3. When does it happen? | |

| 4. Who is present (people, animals)? | |

| 5. Why does the family think the behavior occurs? | |

| • Initial circumstances. Can the owner identify any events that might have caused the problem? | |

| • Environmental changes preceding appearance of problems | |

| • Duration | |

| • Frequency | |

| • Stimuli that trigger the behavior | |

| • Change in appearance | |

| • Treatment attempted and pet’s response | |

| Additional problems | • Are there any behavior problems that are separate from the principal problem? |

Scheduling the behavior consultation

Behavior consultations are like medical consultations in that there rarely are quick fixes you can offer to mend a long-standing problem. A significant amount of time is required to diagnose the problem, determine the prognosis, formulate a safe and effective treatment plan, and present the treatment plan so that the owners can fully process the information and make informed decisions about committing to an action plan. A consultation requires the time and commitment of both veterinarian and client. An action plan cannot be determined until all factors related to the pet’s health, the problem, the level of risk or danger, the environment, the family, and the owner’s commitment to proceed have been assessed. Rarely is it possible to offer any meaningful behavioral advice for a difficult problem during a 15–20-minute routine office visit. Schedule 1–2 hours for the initial interview. Whenever possible, have all members of the family present. See Chapter 1 for a discussion of the economics of behavior visits.

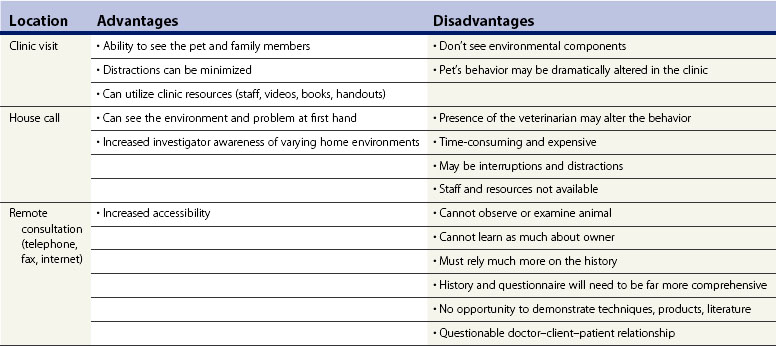

There are also considerations as to where the behavior consultation should take place. Since the history with respect to the environment can be an important component for some problems, a house call can be a practical way to assess first-hand where the pet lives, how it is housed, and the role that the environment might play in the management of the problem. However, a house call may be impractical for some practitioners and costly for clients, and may not have a significant impact on success if the consultant has good history taking skills. The advantages and disadvantages of each are discussed in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 The advantages and disadvantages of different locations for behavioral consultations