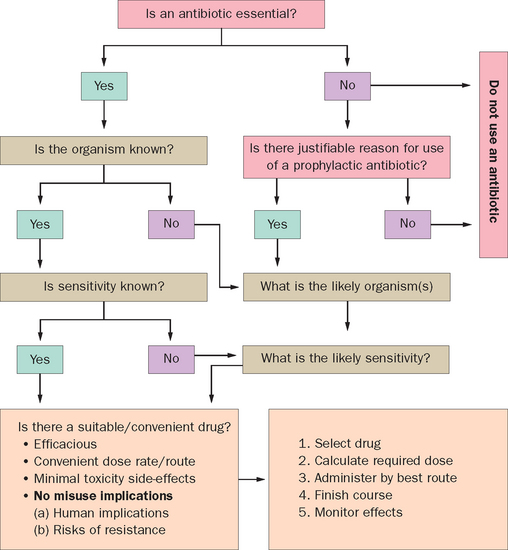

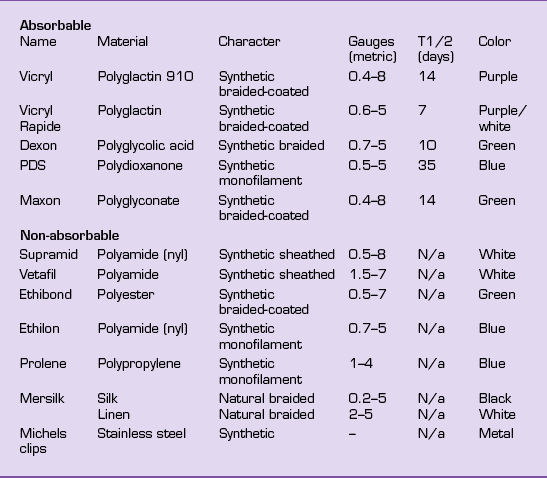

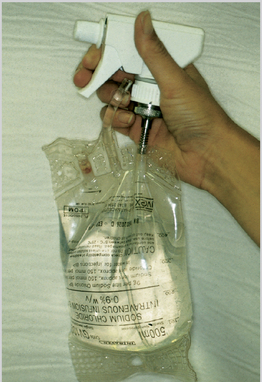

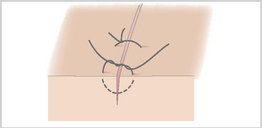

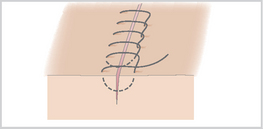

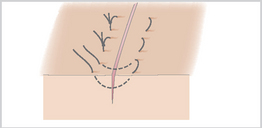

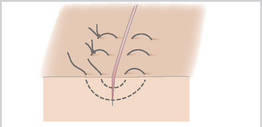

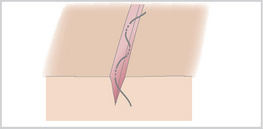

6 After any emergency treatment, such as arresting serious hemorrhage, the horse should, if possible, be moved to a more suitable environment for assessment and treatment. All wounds must be promptly and thoroughly examined to determine the exact site, depth and direction of the wound, and which anatomical tissues and structures are involved and to what extent. It is essential to determine whether important structures, e.g. joints, tendons, nerves, or blood vessels have been damaged. The risk of complications may thereby be minimized and the owner appraised of possible complications in healing at the outset of treatment. Time spent in wound preparation is never wasted, and failure to prepare the wound correctly or fully is a common cause of failed/delayed healing. Ideally washing the wound with sterile saline under minimal pressure is best but (warm) running water is commonly used until any gross contamination is dislodged. The final wash should be with normal saline to restore physiological status. Care should be taken to ensure that this does not drive foreign matter into the depths of the wound. If the wound has bled heavily, washing may loosen the blood clot and restart hemorrhage, which may then need to be controlled (see p. 125). Before clipping, the wound should be packed with a hydrogel or an inert, water-soluble jelly (K-Y Jelly; Johnson and Johnson). After initial clipping and cleaning of the surrounding skin, the hydrogel can be irrigated out of the wound using warm sterile saline under mild pressure (3–5 psi). A solution of 0.5% chlorhexidine is a standard wound antiseptic with minimal harmful effects and can be used if the wound is heavily contaminated or is over 2–4 hours old. Fresh wounds probably do not need an antiseptic wash. Flaps of skin should be lifted and irrigated carefully. A moist wound healing environment has become standard practice. Wounds heal better when maintained in this fashion10. Hydrogels, hydrocolloids, and collagen dressings support a moist environment. Hydrophilic, gas permeable, waterproof polymeric foam dressings should be used in the initial stages of wound management. These foams are available in various shapes to allow cavity management. Alginate or highly absorptive dressings may be required if exudate is excessive. Incised wounds (see p. 8) frequently lend themselves to suturing. Suturing should only be carried out when so doing will have a positive advantage and minimal harmful effects. Careful selection of suture patterns will make a considerable difference to wound healing. The standard patterns and their advantages and disadvantages are described on p. 48 and in standard surgical texts. No wound should be completely closed unless the deeper tissues are effectively sterile. Factors that are likely to result in wound breakdown (dehiscence) after suturing include: This is used in relatively clean but contaminated wounds with extensive tissue damage. The wound is cleaned, debrided and dressed with a hydrogel (Intrasite Gel or Intrasite Conformable; Smith and Nephew), and a polymeric foam dressing (e.g. Allevyn, Smith and Nephew) applied. Cavity dressings (Allevyn Cavity or Intrasite Conformable; Smith and Nephew) or shaped dressings (e.g. Allevyn Heel; Smith and Nephew) can be used in awkward sites. Contraction is very weak in the distal limb regions of horses in particular (see p. 20). Second intention healing is faster in ponies than in horses, and faster on the body trunk than on the limbs where, at least in a proportion of larger horses, the inflammatory process is weak and prolonged and so the wound never heals11. The side-effects of antibiotics include: Tetanus vaccination status should be established in all cases. If the horse has had a recent vaccination then there should be no risk of the disease, as the vaccine is highly effective. Where the vaccination history is dubious, either a tetanus toxoid booster vaccination or antiserum (or both) should be administered. Wound lavage is an essential part of the management of fresh and older wounds. It is used to remove adherent and non-adherent bacteria and foreign matter from the wound without compromising the physiological status of the tissues involved. The two major factors are the type of fluid used and the pressure of the fluid used. Figure 38 The Mills wound irrigator system provides physiologically sound, sterile irrigation at an ideal pressure. It is both convenient and efficient. Povidone iodine is commonly supplied as a 10% solution. The active ingredient is free iodine; dilute (0.1–1%) solutions have greater bactericidal activity than the full strength product. Serum can reduce activity (by binding free iodine) and there is only a short-lived residual effect, hence if used to maintain cleanliness of a wound, 4–6 hourly repetition is necessary. Dilute antibiotic solutions, e.g. penicillin, ampicillin, neomycin, kanamycin, and gentamicin, have been beneficial when added to lavage solutions. However, the solutions usually have an inappropriate pH for wound healing, and so some cell damage is expected. Suspensions of antibiotics and ointments are not appropriate for wound lavage. Antibiotic creams used for bovine mastitis treatment are not suitable for wound management and should never be applied to a healing wound. Sutures are used to close a wound and are used for first intention (primary union) healing (Table 3). Sutures are also used in delayed primary healing. The decision to suture a wound must be based on sound understanding of the likely healing processes involved. Primary closure is the best method of closing and healing a skin wound, but is only applicable to a relatively narrow range of accidental wounds that fulfill certain criteria: the wound should be fresh, clean, and there should be no foreign matter within the wound bed. In addition, once closed by suturing there should be no tension on the wound (unless suitable tension relieving mechanisms can be applied), including during movement or swelling, and there should be no dead space within the wound. Figure 39 The suture is made by a single ‘bite’ through the tissue on each side and the knot is drawn away from the apposed wound margin. Figure 40 The initial simple suture is tied and one end is then carried forward to repeat the process to the end of the wound in slightly oblique parallel bites. The final knot is formed from the double end of the suture material and the loop of the last stitch. Figure 41 The suture is started as for the simple continuous suture but is continued as paralled bites with a return through the previous loop. The knot is ended as for the simple continuous suture. Figure 42 An initial deep bite is taken and then returned at the same depth. The knot lies below the two upturned wound margins. Figure 43 A deep bite is taken as for a simple interrupted suture and then very shallow ‘return’ bites are taken directly above the first deep bite to appose the skin margins. Figure 44 The first knot is placed subcutaneously and tied. Repeated horizontal bites are taken on opposite sides of the wound remaining in the subcuticular tissue. The last knot is tied deeply and the free end is drawn distally by inserting the needle through the skin the same distance away from the wound and cutting it off under mild tension. Figure 45 A vertical mattress suture is laid to include a stent on one or both sides of the wound margin Figure 46 A horizontal mattress suture is laid with short pieces of soft rubber or plastic tubing on either side of the suture. The tube should be the same length as the horizontal displacement of the suture to avoid distortion.

Basic Wound Management

Initial Examination

Initial Cleaning

Provision of a Moist Environment

Wound Closure

Primary Closure

Delayed Primary Closure

Second Intention Healing

Antibacterial Support

Wound Lavage

Lavage Fluids

Povidone Iodine

Soluble Antibiotics

Skin Wound Repair

Suture Patterns

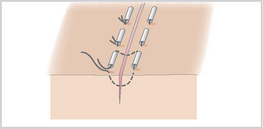

Simple Interrupted Sutures (Figure 39)

Simple Continuous Sutures (Figure 40)

Forward Overlocking (Continuous) (Blanket) Sutures (Figure 41)

Horizontal Mattress (Interrupted or Continuous) Sutures (Figure 42)

Vertical Mattress Sutures (Figure 43)

Subcuticular Sutures (Figure 44)

Supported Quill Sutures (Figures 45, 46)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

. History

. History . Restraint

. Restraint . Initial Examination

. Initial Examination . Wound Lavage

. Wound Lavage . Bandages, Dressings and Dressing Techniques

. Bandages, Dressings and Dressing Techniques . Management of Wound Exudate

. Management of Wound Exudate . Management of Granulation Tissue

. Management of Granulation Tissue