CHAPTER 15 Bacterial Infections

Role of Bacteria in Juvenile Small Animal Disease

There are relatively few bacterial diseases to which juvenile animals are inherently more predisposed in comparison to adults. This starkly contrasts with their vulnerability to viral infections (see Chapter 16). This chapter covers the most common syndromes in which bacteria act as primary pathogens in juveniles, as well as some practical considerations in obtaining definitive diagnoses in working with a diagnostic laboratory.

Classification of Bacteria

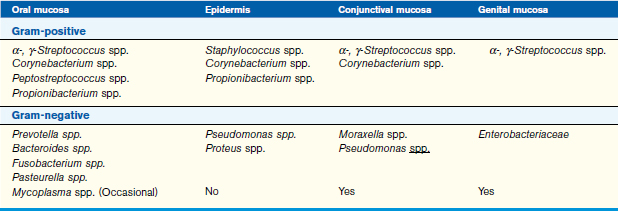

Bacteria are most commonly classified by their cell wall type and their ability to grow in the presence or absence of oxygen (aerobic/anaerobic). The majority of pathogens can be classified according to cell wall type with a Gram stain; however, some microbial genera, such as Mycoplasma and Chlamydophila, stain poorly. Other staining agents help to identify agents more specifically such as the Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain for mycobacteria. Knowledge of predilections of bacterial families to colonize particular body sites is useful in empirical selection of antimicrobial agent(s) for initial therapy (Table 15-1).

Systemic Infections

General Neonatal Septicemia and Bacteremia

Because these diseases progress rapidly in neonates and sudden death often occurs, the problem is frequently diagnosed postmortem. Typical histopathologic findings include bacterial emboli in multiple organs, and if culture is performed on fresh tissues, one bacterial species typically dominates as a pure culture in high numbers. Expired animals submitted for histopathology should be refrigerated (not frozen) and sent to the diagnostic laboratory intact within 1 day. If animals are too large to send in their entirety, they should be necropsied as soon as possible with fresh and fixed tissues collected for histopathologic examination and ancillary testing (Table 15-2).

TABLE 15-2 Samples for postmortem diagnosis of the acutely dead neonate

| Fixed tissues for histopathology (10% buffered formalin) | Fresh tissues for bacteriology, virology, serology |

|---|---|

| Heart (LV, RV, septum), lung, kidney, adrenal glands, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, urinary bladder, spleen, cerebrum, thyroid gland, cerebellum, brainstem, trachea, tongue |

LV, Left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

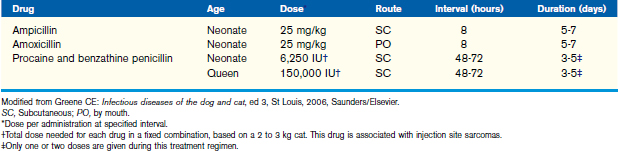

Prevention of some infections can be achieved by administering antimicrobial agents to queens in the peripartum period (Table 15-3), if there is a known or suspected genital colonization by β-hemolytic streptococci. Proper sanitation of the birthing area is also essential in the prevention of both umbilical infections and neonatal septicemia. Antiseptic solutions, such as povidone-iodine, should also be applied to the umbilicus of the neonate to help prevent umbilical infections.

Treatment of neonatal systemic infections involves antimicrobial agents and supportive care. Balanced electrolyte solutions, such as lactated Ringer’s solution or Normosol R, should be used for fluid therapy. Some patients may require dextrose or potassium chloride supplementation as part of their fluid therapy. Patients that are profoundly hypoglycemic should receive a bolus (1 to 2 ml/kg) of 50% dextrose that should be diluted to make a 10% to 25% solution. Thermal support, oxygen supplementation, and nutrition are also important elements of supportive therapy for the bacteremic patient (see chapter 10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree