Chapter 142 Auscultation and Physical Diagnosis

Physical examination follows the obtaining of a complete history and the consideration of the species, age, breed, and sex (see Chapter 1). Diagnosis, or at the very least a number of plausible diagnoses, may be made in many instances by history and signalment; however, following a thorough physical examination, a single, “most likely” diagnosis can be made with reasonable assurance in most patients with cardiac problems.

INSPECTION

Condition, Attitude, and Posture

Mucous Membrane Color

Cyanosis

Abdominal Distention and Edema

Pattern of Ventilation

Cough

Cough is a sign of both heart and lung disease. It may be characterized as follows:

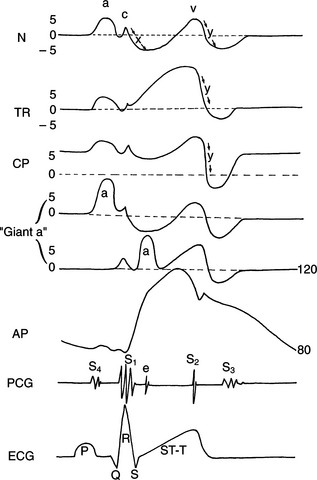

Jugular Vein Evaluation

Analysis of the jugular vein (Fig. 142-1) is simpler if the hair is clipped from around the jugular furrow or if it is moistened with 70% alcohol. Look for pulsations in the vein and estimate the pressure distending it.