47 Ataxia

Spinal ataxia

INTRODUCTION

Causes of ataxia

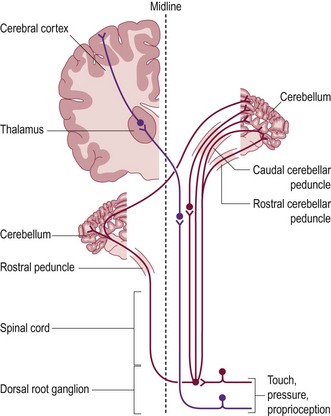

Position sense is referred to as proprioception and is achieved through muscle, tendon and joint receptors, associated sensory nerves, and ascending tracts within the spinal cord (Fig. 47.1).

Presenting signs of abnormal proprioception

• Excessive abduction of a limb, or both limbs causing a wide-based stance, or more extreme, a splaying of the limbs (‘Bambi on ice’)

• Circumduction (swinging out to the side; abduction in an arc-shaped trajectory) of the limbs, particularly when turning

• Stumbles, tripping over steps, own adducted limb, on uneven ground or surfaces with little traction, e.g. wood flooring

• Delayed initiation of a step (delayed protraction) resulting in a longer stride than normal. This gives the hindquarters a crouched appearance. This may result in collapse when turning.

Owners commonly describe their pet as ‘drunk, wobbly, clumsy or unsteady’.

CASE HISTORY

Hindlimb ataxia began 6 days before presentation and slowly worsened. The dog was unable to walk more than a few steps before the hindlimbs crossed and tripped each other (Fig. 47.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree