CHAPTER 20 Approach to the Febrile Patient

Thermoregulation

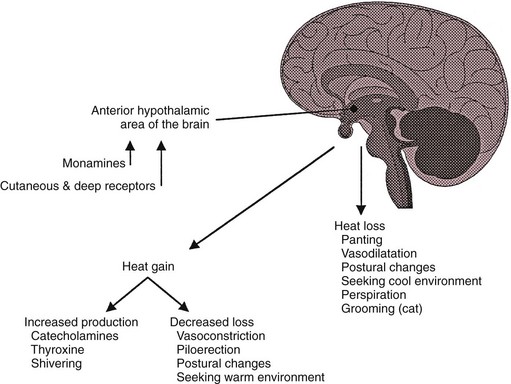

The thermoregulatory center for the body is located in the central nervous system (CNS) in the region of the anterior hypothalamus (AH). Changes in ambient and core body temperatures are sensed by the peripheral and central thermoreceptors, and the information is conveyed to the AH via the nervous system. Thermoreceptors sensing that the body is below or above its normal temperature (normal “set point”) will stimulate the AH to cause the body to increase heat production and reduce heat loss through conservation if the body is too cold or dissipate heat if the body is too warm (Figure 20-1). Through these mechanisms, dogs and cats can maintain a narrow core body temperature range in a wide variety of environmental conditions. With normal ambient temperatures, most body heat is produced by muscular activity, even while at rest. Patients with severe neurologic impairment or cachexia and those under anesthesia may not be able to maintain a normal set point or generate a normal febrile response.

Figure 20-1 Normal thermoregulation.

(From Miller JB: Hyperthermia and fever of unknown origin. In Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC (eds): Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 6, St Louis, 2005, Saunders/Elsevier.)

Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia is the term used to describe any elevation in core body temperature above the accepted normal for that species. Hyperthermia is a result of the loss of equilibrium in the heat balance equation such that heat is produced or stored in the body at a rate in excess of heat lost through radiation, convection, or evaporation. The term fever is reserved for those hyperthermic animals in which the set point in the AH has been “reset” to a higher temperature. In hyperthermic states other than fever, the hyperthermia is not a result of the body attempting to increase its temperature but is caused by the physiologic, pathologic, or pharmacologic intervention in which heat gain exceeds heat loss. Box 20-1 outlines the various forms of hyperthermia.

Exogenous Pyrogens

True fever may be initiated by a variety of substances, including infectious agents or their products, immune complexes, tissue inflammation or necrosis, and several pharmacologic agents including many antibiotics. Collectively, these substances are called exogenous pyrogens. Their ability to directly affect the thermoregulatory center is probably minimal, and their action is to cause the release of endogenous pyrogens by the host. Box 20-2 lists some of the more important known exogenous pyrogens.

Endogenous Pyrogens

In response to stimuli by an exogenous pyrogen, proteins (cytokines) released from cells of the immune system trigger the febrile response. Macrophages are the primary immune cell involved, although T and B lymphocytes and other leukocytes may play significant roles. The proteins produced are called endogenous pyrogens or fever-producing cytokines. Although interleukin-1 (IL-1) is considered the most important cytokine, at least 11 cytokines capable of initiating febrile responses have been identified (Table 20-1). Some neoplastic cells are also capable of producing cytokines that lead to a febrile response. The cytokines travel via the blood stream to the AH, where they bind to the vascular endothelial cells within the AH and stimulate release of prostaglandins (PGs), primarily prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and possibly prostaglandin E2α(PGE2α). The set point is raised, and the core body temperature increases through increased heat production and conservation (Figure 20-2).

TABLE 20-1 Proteins with pyrogenic activity

| Endogenous pyrogen | Principal source |

|---|---|

| Cachectin/tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) | Macrophages |

| Lymphotoxin/tumor necrosis | Lymphocytes (T and B) factor-β (TNF-β; LT) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|