There is a danger that palliative therapy perpetuates the lives of suffering animals by inhibiting a euthanasia decision from the owner. Firstly, offering palliative care provides owners with an attractive option which sounds acceptable, even if it does not raise the animal’s quality-of-life to the level of a life-worth-living, and which allows owners to defer making an irreversible decision. Palliative care can therefore cause a major iatrogenic harm by perpetuating a life-worth-avoiding. Practitioners need to balance advocating the palliation of suffering and not perpetuating a poor quality life, for example by strongly recommending euthanasia, providing only short-term prescriptions of treatments and being prepared to report owners who refuse consent to authorities.

In contrast, veterinary treatments can also directly affect the symptoms of welfare harms. For example, behavioural modification can alter animals’ behaviours, without addressing the underlying causes. Such treatments may be in the interests of the client. But they are not in the interests of the animal if they only alleviate signs, because of the potential for iatrogenic harms. Purely symptomatic treatment is therefore not welfare-focused, except where it addresses behaviours that are the causes of harms (e.g. avoiding self-mutilation). For this reason, it might be better to consider this discipline of veterinary medicine not as behavioural medicine but as animal psychiatry.

Figure 5.2 Providing good post-operative pain relief is an important part of surgical skill. (Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Good welfare-focused choices can also improve welfare by reducing iatrogenic harms. Analgesia can often control pain from operations, and surgical descriptions increasingly include laudable recommendations on routine analgesia usage (Figure 5.2). Routine analgesia does not imply one-size-fits-all medication, and recent years have seen a focus on using multimodal, combinatorial regimes and tailored regimes for individual patients.

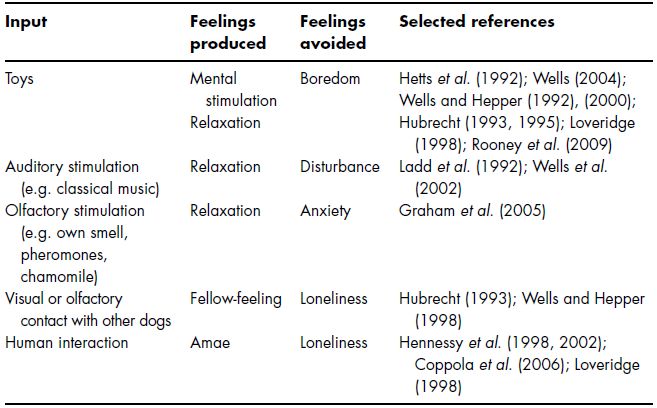

Practitioners may also take steps to reduce the problems caused by hospitalisation, isolation and stable rest. We should provide sufficient bedding, keep ambient temperatures within patient’s thermoneutral zones (and ill animals may be comfortable in different temperature), try to replicate patients’ normal routines where possible, and use pleasant ambient aromas, species-specific pheromones or familiar smells (Figure 5.3). Environmental enrichment, including human company (Figure 5.4), can also help reduce stress and even improve health (Table 5.1).

Veterinary professionals can minimise vet-fear by taking care over their comportment and handling. This involves avoiding methods that can cause pain (e.g. punishment and picking rodents up by their tails) or fear (e.g. intimidating eye contact, unnecessary invasions of body space or flight zones and sudden movements). In some cases, patients should see specific staff where they have a preference or where certain colleagues have previously performed unpleasant interventions. Where possible, vet-fear can be decreased or prevented by longer-term efforts, such as providing pleasant experiences (Simpson 1997), especially during socialisation periods (Lindsay 2005). For example, dogs can be trained to be muzzled through pleasant and gradual small steps (Rooney et al. 2009), and this may be done by owners at home. Some patients may even end up enjoying coming into the practice (and such vet-love is a good success criterion for one’s handling skills).

Figure 5.3 Pheromones in kennels may reduce the iatrogenic harm of hospitalisation. (Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Figure 5.4 Appropriate human contact can provide enrichment for some hospitalised patients. (Courtesy of SPCA Hong Kong.)

Table 5.1 Key inputs that can reduce iatrogenic harms of hospitalisation for dogs.

Efforts to minimise iatrogenic harms effectively constitute treatments. So they can cause more iatrogenic harms. Thus, veterinary professionals need not only to consider how to minimise the effects of their treatments for pathological causes of feelings, but also how to minimise the effects of their treatments for iatrogenic causes of feelings (and so on).

5.2 Tackling Owner Causes of Feelings

Owners can assist or frustrate our efforts to address pathological and iatrogenic causes of unpleasant feelings. It is usually the animal’s owner who calls a veterinary professional out to see the animal or brings it to the surgery, provides a history, consents to the procedures and pays for the treatment. They then administer medication, comply with recommendations and bring the animal in for follow-up checks or if something goes wrong. Owners are even more significant in our efforts to tackle owner-related causes of welfare harms. For these cases, owner changes are the main – or only – way to improve patients’ welfare, for example to improve husbandry (e.g. diet or care) or human–animal interactions (e.g. exercise and training). There are a number of different ways the owner factor can be managed, including legal, economic and communicative methods.

Legal methods include refusing to give a treatment that only veterinary professionals can legally provide or reporting the owner to authorities for criminal offences. In some cases, one can rehome the animal, so that a new owner has the legal property rights to make decisions about the animal. Indeed, owners are so important that sometimes the best way to improve an animal’s welfare is to get the animal another owner.

Economic methods include charging for overtreatment, providing subsidised or free treatment, utilising charities money and using conventional commercial marketing techniques that hard sell animal welfare goals.

Communicative methods involve utilising the interactions within the consultation. Communication is an important element of veterinary work, and evidence from human medicine suggests better communication is associated with fewer errors, higher patient satisfaction, greater compliance and less litigation (DiMatteo et al. 1993; Stewart 1995; Silverman et al. 2005).

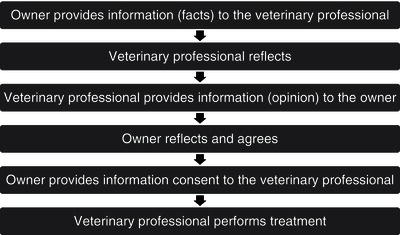

We tend to imagine communication to be a rational, cognitive exercise, where the owner provides information, upon which we reflect, and then we provide information and authoritative opinion, upon which the owner reflects and then agrees (Figure 5.5). But this is a myth. Communication is a matter of myriad cultural and psychological factors (Fielding 1995), and involves a range of sophisticated personal skills that require intuition and emotional intelligence. Veterinary professionals used to have to learn such skills as they went along (Adams & Frankel 2007), but veterinary communication is developing as a field of research and education. This education is often informed by human medicine, although veterinary communication is different, since it involves discussion about a third party. Communication in small animal work is more similar to paediatrics, although non-human animals are different to children.

| P | Use of prompts to remind clients |

| I | Active involvement of the person in the decision |

| N | Use of norms, i.e. relative to what other people do, or other animals |

| O | Gaining ownership in the process and outcomes |

| C | Use of credible community leaders and personal contact |

| C | Getting commitment, ideally in writing |

| H | Hooks to draw the client into the discussion and decision-making |

| I | Identifying the people most likely to change |

| O | Displaying owner benefits and addressing owner barriers |

One area of communication research that is especially relevant to achieving animal welfare goals is social marketing. This field concerns what strategies can best change how people behave (it was largely developed through efforts in environmental and health fields such as recycling and anti-smoking campaigns). Because social marketing is concerned with motivating behaviour change, it could be especially useful in helping us work out how to achieve owner behaviour changes that can improve their animals’ welfare. Many different communication tactics have been suggested for social marketing campaigns (Box 5.1).

Using these methods, veterinary professionals can guide and assist owners through their decision-making process. But before considering how veterinary professionals can best communicate with clients, it is worth remembering that good vet–client communication also requires owners to communicate well. In 2004, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry produced a list of points relating to how patients should communicate. An expanded and adapted form for veterinary professionals is given in Box 5.2. Unfortunately, and evidently, most clients receive no communication skills training. They too have to learn as they go along. Fortunately, we can help them to learn by advising them on their communication. At the very least, we can encourage them to be honest and candid. Of course, this communication-about-communication needs especially good communication skills.

- Come prepared

- Be punctual and presentable

- Control their animal and children

- Be honest

- Be realistic about their limitations (e.g. finances and animal handling ability)

- Respect veterinary practice staff, other clients and animals

- Listen carefully

- Make efforts to remember (e.g. taking notes)

- Speak enough – but not too much

- Give relevant information

- Avoid giving irrelevant information

- Make only reasonable demands

- Ask questions

- Take advice

- Accept bespoke solutions where they represent compromises due to owner limitations (e.g. finances)

- Raise any concerns or queries

- Be prepared to finance reasonable treatment options

- Pay bills promptly

5.3 Improving Owners’ Assessments

Veterinary professionals can guide owners’ assessment for all three of the steps involved. We can increase owners’ awareness by informing owners about the existence of welfare problems. We can improve their interpretation by explaining what symptoms mean in terms of animal welfare, providing diagnoses and aetiologies, describing prognoses, treatment options and possible sequelae, and explaining the implications of options in terms of their costs and effect on owners’ lifestyle. We can also provide useful background knowledge to improve their prior understanding, guidance on their interpretation and specific advice to target any emotional biases. Giving information to owners is an important method for changing owners’ behaviour (Patronek et al. 1996) and reducing non-compliance (e.g. Stimson 1974).

There are several limitations to providing information to owners. One is their comprehension, which may depend on their general knowledge, linguistic abilities, prior understanding and any emotional biases. To address these, veterinary professionals should provide information in ways owners can understand. What information we provide should focus on what information owners want and need to know in order to make the best decision (e.g. information on prices, prognoses and welfare implications), and not on unimportant information (e.g. the exact nature of the procedure, the names of the drugs or the exact diagnosis).

Owners often struggle to understand scientific data that may underlie veterinary professionals’ interpretations. But they can appreciate how they would feel if they were in a similar situation to their animal. This can make critical anthropomorphism a valuable communication tool (regardless of its usefulness as a welfare assessment method). As discussed in Chapters 1 and 3, this approach should be used with caution, because excessive anthropomorphism can lead to inappropriate treatment decisions.

Owners also frequently struggle to understand probabilities, especially very large or small risks, or where the outcomes that may occur are emotionally charged. It can be useful to express a risk in terms of how often the relevant outcome would be expected to occur (e.g. 1 animal in 10 is alive after 6 months). Where owners are disproportionately concerned about one risk and not another, it can be useful to compare the relative risks between one treatment option and another or between a benefit and a harm. For example, a radical surgery may have a 1% chance of extending life but a 100% chance of causing significant pain and frustration.

Other limitations of communicating information concern the veterinary professionals ourselves. We may fail to devote enough time to giving, explaining or repeating information. We may use terms that make owners less receptive, defensive or scared. Indeed, even the term welfare can seem like an accusatory term, especially in those countries with well-known welfare laws. We may spend too long explaining irrelevant details (which we find interesting) or use unnecessarily technical language or acronyms. In fact, these technical terms can be confusing even if we also use commonplace words alongside, and it is often better to use only the lay word.

One can raise owners’ awareness through explicit joint welfare assessment. Screening methods allow veterinary professionals to demonstrate the broad scope of issues that may affect an animal’s welfare and to give advice even where there is no immediate reason to do so without seeming interfering or hard selling. Welfare assessment by owners may encourage them to seek veterinary treatment. Such engagement appears to work in human medicine (Roter 2000; King & Moulton 2006; Griffiths et al. 2007), including human paediatrics (Janicke et al. 2001), and in farm animal welfare initiatives (Catley et al. 2002; Vaarst et al. 2007).

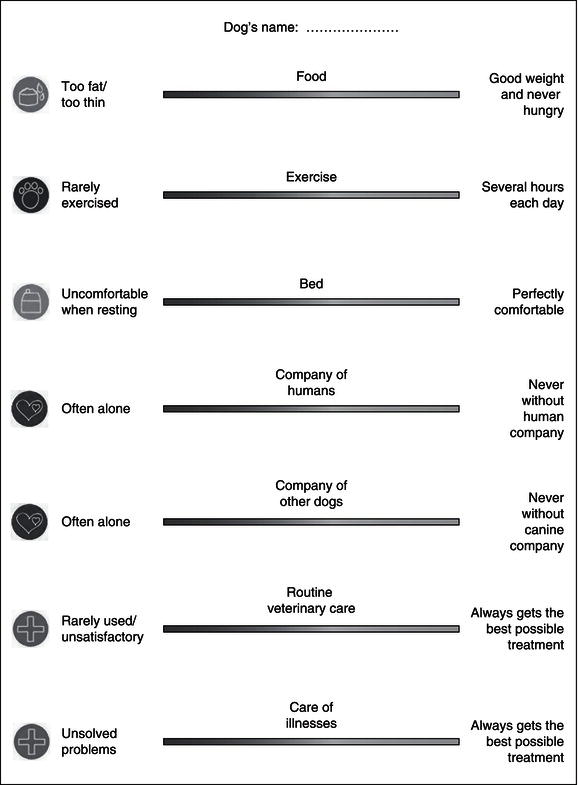

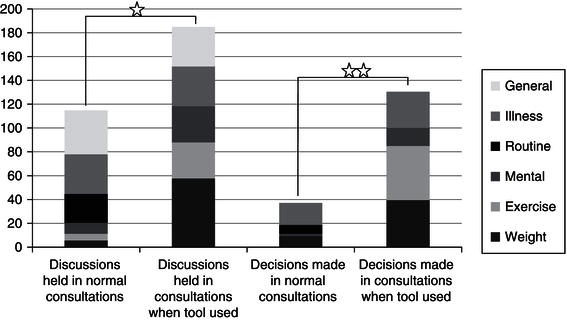

A participatory tool was recently developed for dog welfare assessment in practice (Figure 5.6), and the designer found it very useful both in raising issues efficiently and in getting clients to commit to changing how they care for their animal (Yeates et al. 2011), as shown in Figure 5.7. Other veterinary professionals also found the tool useful, but less so. This suggests that it is useful to design one’s own tool for one’s own clients. By the same logic that we have said applies to owners, being involved and engaged in designing a tool means you can tailor it to your own style and clients, and have ownership of the tool. It is good to design, or adapt, your own welfare assessment tool for use in your own practice.

Figure 5.6 A participatory tool on which owners can assess their dog’s welfare. (After Yeates et al. 2011.)

Figure 5.7 Number of discussions owners had with their veterinary professional and decisions they made (per 100 consultations) during normal consultations and during consultations using the participatory tool. (After Yeates et al. 2011.)

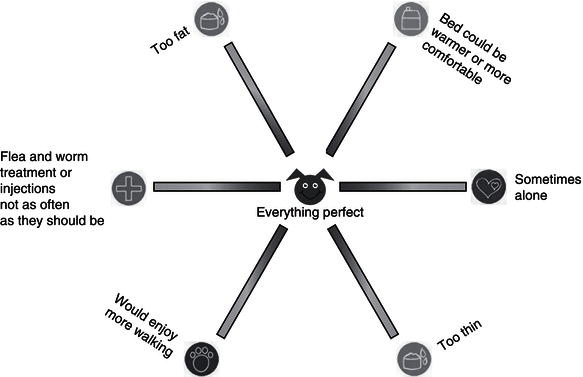

Other participatory methods could be adapted from methods used in rural communities and developing countries. For example, owners could be asked to rate how good their animal’s welfare is based on six outcome measures, using the welfare circle in Figure 5.8. More pictorial owners might be asked to draw a map of their animal’s environment, or the animal’s body, highlighting any actual and potential problems. More mathematical owners could draw a graph of their animal’s welfare over time (e.g. during a chronic illness), including any significant events that have changed it.

5.4 Improving Owners’ Evaluations and Choices

Veterinary professionals can also help owners to evaluate and make welfare-focused choices. Recognising owners’ benefits and barriers allows you to correct erroneous assumptions and point out benefits they may have missed. It can be useful to highlight pros and cons, and one can create decision-making aids that list benefits and risks, using either pre-prepared tools or bespoke methods.

Social marketing research suggests that we are all motivated by other people, either consciously or subconsciously. Given the social expectation about animal welfare, owners may wish to avoid criticism for failing to look after their animal. Veterinary professionals can utilise this motivation to enhance welfare contagion, by reminding owners of the societal morals, by bringing farmers together to discuss welfare issues and by providing feedback that rank farms’ welfare scores.

Veterinary professionals can also spread contagion to our clients by using our position as key opinion leaders based on our recognised expertise, our role in the community, our professional status and our acknowledged responsibilities to put animals’ interests before our own. We can also provide advice and act as role models (and veterinary practitioners can set a bad role model, e.g. through inappropriate animal handling).

We should also think it acceptable to hard sell welfare improvements. We should offer the best and not only advocate it but should also use our influence and authority to push the client towards whatever is best for welfare. There are many ways to influence owners, based on the ideas discussed in this chapter (Table 5.2). The idea of hard selling may seem distasteful, but if animal welfare is veterinary professionals’ primary responsibility, then we should strive to achieve it.

Veterinary professionals’ influence also comes from our relationship with the client. Relationships are an important part of health care (Beach & Inui 2006) and improving relations can increase adherence (Brown & Silverman 1999). Making oneself more relationship-oriented requires the use of specific strategies and the development of certain habits (Frankel et al. 2003). For example, the strategies in Box 5.3 appear to increase human–patient satisfaction scores (Stein et al. 2005) and are applicable to veterinary medicine (Adams & Frankel 2007). This can be more difficult with certain clients, or when communication is through a translator, but not impossible.

Table 5.2 Significant forms of veterinary influence over owners.

| Form of influence | Examples |

| Prominence | Encouraging owners to identify welfare issues |

| History and education | Choosing specific elements to assess |

| Memory | Prompts |

| Presentation of information | Presentation of elements |

| Moral priming | Choosing specific elements to assess |

| Human–animal relationship | Highlighting animal’s interests |

| Societal influence | Using social norms |

| Value-loading information | Choice of terms |

| Emotional priming | Displaying owner benefits |

| Engaging in reasoning | Joint decision-making methods |

| Personal suggestions | Using authority |

| Encouraging certain opinions | Promoting ownership of the problem |

| Peer pressure | Personal contact |

| Coercion | Active involvement |

| Forcing options | Getting commitment |

| Owner-based barriers/capacities | Addressing barriers |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree