9 Noninfectious Musculoskeletal Problems

Case 9-1 Foal with Flexural Deformity

’03 UpTight, a Dutch Warmblood cross filly (Figure 9-1) was born with moderate to marked buckling forward of the right carpus and mild buckling forward of the left carpus as well (Figure 9-2). ’03 UpTight’s dam, a 10-year-old Thoroughbred mare, had produced two normal foals previously and was considered to be in good body condition. The mare was allowed free choice pasture exercise with access to a run-in stall 24 hours a day and was supplemented with a balanced ration of grain and timothy hay. The birth was attended, and no assistance was necessary.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Frequently there is nothing in the history that will predict flexural limb deformities. Answers to questions about the possible ingestion of toxic plants or exposure to known teratogens are usually negative. In cases of severe contractual deformity, dystocia may have occurred because the foal is unable to assume the correction position for delivery. A history of placentitis or twinning may result in a premature parturition and a foal with hyperextension. In any limb deformity, close questioning about the timing and amount of colostrum ingestion is important. Foals that have difficulty standing and nursing due to orthopedic reasons are at high risk for failure of passive transfer and sepsis (see Chapters 3 and 5).

The flexural deformity of the carpus in the above foal is hyperflexion, which is readily diagnosed at birth. The degree of overflexion may be very mild or it may be so severe as to result in dystocia and/or the inability of the foal to stand. The disorder may involve one limb or both. It may also be present in the metacarpophalangeal joint(s), and less commonly the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. Flexural deformity of the DIP joint may be present at birth but is much more common in foals older than four weeks of age.1 Tarsal and metatarsophalangeal joint involvement have also been reported but are rare.2

Similar to that described in the above case, manipulation of the limb is used to determine the severity. This can be done with the foal restrained and standing or with the foal in lateral recumbency. As above, the carpus is manually pushed backward as the cannon bone is held stationary (Figure 9-3). Mild deformities will often straighten easily with manipulation, but moderate to severe hyperflexures will rarely do so completely. The ability to fully flex the joint should also be determined. An uncomplicated flexural deformity will have normal flexion.

Fig. 9-3 Attempts to straighten the carpus helps to determine the severity of the flexural contracture.

When observed from the side, foals with metacarpophalangeal joint flexural deformity appear to knuckle over at the fetlock (Figure 9-4). When severe, it is difficult for the foal to walk, and the foal may walk on the dorsum of the joint. When evaluating a foal with this type of deformity, it is important to check if the sole of the foot makes contact with the ground. Resolution is more difficult in those that don’t.

Fig. 9-4 A foal with metacarpophalangeal joint flexural deformity appears to knuckle over at the fetlock.

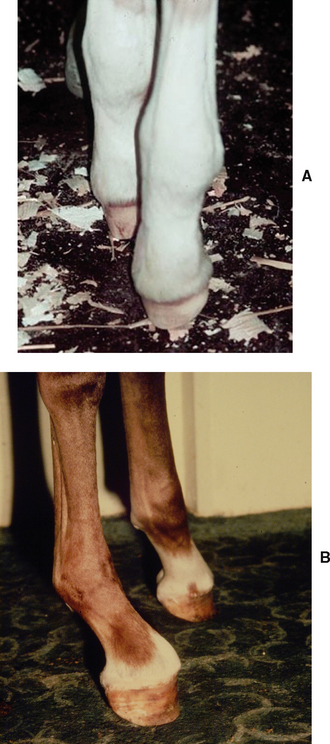

Flexural deformity of the distal interphalangeal joint may also result in the foal walking on the toe. Differentiation between problems arising from the metacarpophalangeal joint and the distal interphalangeal should be made. With involvement of the third phalanx only, the foal will have normal angulation of the fetlock and first and second phalangeal alignment. The hoof wall angle, however, is more upright than the angle of the pastern. Over time, the heel length will grow and result in the classic clubfoot or boxy foot appearance (Figure 9-5, A and B). Treatment of a foal that is unable to place its foot flat on the ground has a greater chance of success if it is resulting from distal interphalangeal joint versus metacarpophalangeal flexural deformity.3

When performing the physical examination, it is also important to evaluate the common digital extensor tendon over the dorsolateral aspect of the carpus. A rupture should be suspected if there is swelling over the dorsolateral surface of the carpus and can be confirmed by digital palpation or ultrasound imaging of the separated tendon ends (Figure 9-6). Rupture of this tendon may occur in neonates leading to forelimb conformation that may be mistakenly diagnosed as a primary carpal or metacarpophalangeal flexural deformity. Tendon rupture may occur without any other orthopedic problem, or it can be secondary to either a moderate to severe primary carpal or metacarpophalangeal flexural deformity. When the tendon rupture is secondary to a flexural deformity, then manual extension of the limb is not easily achieved.

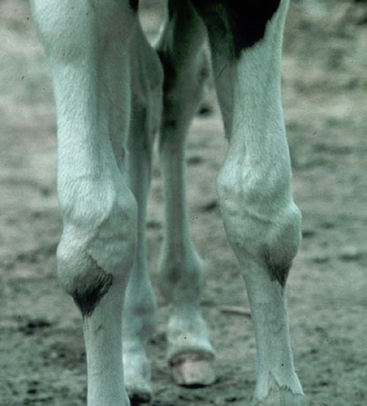

The second form of flexural deformity in the foal is caused by hyperextension or laxity in the foal’s tendon/muscle unit. Hyperextension of the digit is quite common in neonates at birth and following prolonged recumbency associated with illness. The condition is characterized by dorsiflexion of the interphalangeal joints that results in the foal walking on the heel bulbs of the foot and in extreme cases, the palmar or plantar aspect of the phalanges and fetlock, with the toe elevated (Figure 9-7). Digital hyperextension is more common in the hindlimbs but can affect all limbs. Occasionally hyperextension of the carpus can be seen in foals. Fortunately most cases respond favorably over time with minimal intervention.

PATHOGENESIS

Flexural deformities of the limbs may either be congenital or acquired in origin. Acquired contractures in the neonate are rare unless the foal has been recumbent because of illness or is not fully weight bearing on a limb due to lameness. Much more common are deformities seen at birth, with the hyperflexed condition generally restricted to the carpus, the metacarpophalangeal joint, and less commonly the distal interphalangeal joint.2,4 The most common hyperextension disorder occurs in the distal interphalangeal joint.

The pathogenesis of congenital contractual flexural deformities is speculative. Several theories, including ingestion of teratogens, nitrates, sudan grass, or locoweed; neuromuscular disorders; lathyrism; and equine goiter or hypothyroidism have been proposed, but no one theory is supported.5,6 Intrauterine positioning continues to be discussed and may be responsible in some but unlikely all cases as frequent repositioning of the fetus in utero occurs.7,8 Body pregnancies are more likely to present with hyperflexion secondary to in utero positioning because the foal’s movement is restricted in late gestation. Inheritance is less likely as many dams, similar to that in the above case, have had previously normal foals by the same stallion. As with many unknowns, a multifactorial etiology is likely.

In both distal interphalangeal and fetlock hyperflexed deformities, pathology is typically restricted to an incongruity between the length of the flexor tendons and the skeleton.9 In distal interphalangeal cases, the deep digital flexor tendon is involved; in fetlock contracture, both the superficial and the deep digital flexor muscle-tendon units are shortened. In some instances, shortening of the suspensory ligament may be primarily involved. This differs from that of carpal contracture in which rarely is a specific tendon-muscle unit involved. Instead, contracture of the carpal fascia and palmar ligament is more common, which makes treatment of severe cases much more difficult.3

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Few, if any, diagnostic tests are required for the management of neonatal flexural limb deformities of the carpus or metacarpophalangeal joint. Of primary importance is IgG determination to confirm adequate immunologic coverage. Foals that have difficulty rising and ambulating due to moderate to severe contracture are quite likely to have inadequate IgG concentrations, as well as dehydration and hypoglycemia due to inadequate nursing. Radiographic imaging of the affected joint(s) may be pursued but is not necessary in most foals. Exceptions include foals that are lame, have severe contracture, or are unable to flex the joint as well as extend it. Foals with flexural deformity of the DIP joint may also benefit from radiographic examination. Over time, pedal osteolysis develops in foals that have altered blood flow to the foot secondary to abnormal weight bearing.10 Seedy toe and toe abscessation may occur if left untreated.10

TREATMENT

Treatment of foals with flexural limb deformity should be initiated quickly, as early intervention is often more successful and implementable than that pursued as the foal ages.11 Carpal and fetlock hyperflexures generally respond favorably to a combination of controlled exercise, bandaging with or without a splint, and use of intravenous oxytetracycline.8,9,12 Mild contractures often improve within just a few days as the foal becomes stronger with exercise. Exercise should be restricted to firm footing to encourage tendon stretching and to a small paddock for frequent but short amounts of time. With extended periods of exercise, deformities may worsen due to fatigue of the muscles and tendons and the pain associated with their stretching. Ambulatory foals with mild deformities that are not rapidly improving or those with moderate or severe deformities require more aggressive treatment.

The splint is centered over the caudal aspect of the bandage and secured in place with the limb in extension using a nonelastic tape such as duct tape or two-inch white tape. With this type of external coaptation, adequate padding is essential to avoid pressure necrosis of the skin. Skin areas at greatest risk are the medial and lateral malleoli of the distal radius, the accessory carpal bone, and that beneath the distal end of the splint. Ideally the bandages should be changed and the skin examined for sores daily but at minimum every two days. It should be changed more often if the splint slips or the bandage becomes wet. Patches can be fashioned using thick foam (two- to four-inch) to redistribute pressure away from pressure points. Improvement in the flexion of the carpus should be seen after several days. Discontinuation of the splints should be done once the carpus has a normal angle. However, use of the bandages for several days beyond this is recommended as in some foals the flexural deformity will reappear otherwise.

Intravenous oxytetracycline (44 mg/kg per body weight) diluted in 1 liter of polyionic fluid given intravenously is a successful adjunct to bandaging and splinting and may also be effective when used alone to treat some cases.12,13 The mechanism by which oxytetracycline works is not completely understood. Chelation of Ca++ within the skeletal muscle has been theorized, but measurement of Ca++ in clinical cases does not support this.14 Neuromuscular blockade effected by oxytetracycline has also been suggested.15 Neither theory explains why flexor tendon relaxation is targeted over that of extensor tendons.

Clinical and investigative studies have documented improvement in distal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, and carpal joint angles in foals following oxytetracycline administration.12 In 1992 Lokai reported its clinical use in 123 foals with congenital flexural deformities with a 94% success outcome.12 Patients included foals that were less than 14 days of age that were able to place some part of the foot on the ground. A second dose of oxytetracycline was required in foals that did not significantly respond by 48 hours of the initial treatment. The effects of the oxytetracycline can be short-lived (∼96 hours), so retreatment as well as continued support bandaging may be necessary to maintain the improvement. In a controlled study measuring metacarpophalangeal joint angles in normal foals following administration of oxytetracycline (44 mg/kg of body weight diluted in 10 ml of 0.9% normal saline), the initial significant change in metacarpophalangeal angle was not present by day four following administration.14

Oxytetracycline, at this high dose, can adversely affect renal function and thus it should be given only in the well-hydrated, nonseptic foal. Renal parameters should assessed prior to administration of additional doses. Oxytetracycline-induced acute nephrosis has been reported in a foal treated at one day of age with 70 mg/kg per body weight of the drug.16 Although this foal’s subclinical neonatal isoerythrolysis and hypovolemia may have been predisposing factors, the case points to the importance of patient selection and careful monitoring. This reaction appears to be idiosyncratic in nature. Studies looking at renal parameters of foals receiving this high dose of oxytetracycline showed no abnormalities. The diluting of the dose of oxytetracycline in a liter of balanced electrolyte fluid may help to avoid this reaction.

Four layers of fiberglass cast tape (usually three inches in width) are used in light horse breed foals. Seven to ten days is usually adequate to observe marked improvement, and during this time the foal is stall rested with its dam. Anesthesia of the foal is recommended for cast removal. Again, continued bandaging may be necessary to maintain normal extension as was seen in the above case. Bandaging, splinting, and casts effect their action by improving the direction of the weight-bearing forces on the limb so that tension is applied to the flexors. Through an inverse myotactic reflex, relaxation of the muscle-tendon unit occurs.3,17

The use of controlled exercise, bandaging with splints, oxytetracycline, and casts have also been successful in the treatment of metacarpophalangeal flexural deformities.8,12,13 Guidelines for their use are similar to those described for carpal contractures, however, placement of the bandage, splint, and cast are different. For foals with fetlock but no carpal involvement, only the limb below the level of the carpus is bandaged, splinted, or cast. In the latter, the foot is incorporated into the half limb cast. If both the carpus and the fetlock are involved, then a full limb bandage/splint or full limb cast is used.

For those foals with distal interphalangeal joint contracture, corrective farriery may be helpful. A toe extension is used for the treatment of DIP and fetlock flexural deformities.4,9 This plus controlled exercise consisting of hand walking on a firm surface several times a day will generally correct mild deformities. Improvement following short-term use of a half-limb cast has also been reported.4 In foals that fail to respond within one to two weeks or those with more severe flexion, surgical intervention is recommended.

Surgical intervention should be reserved for those foals with severe congenital contractures and those with acquired contractures that fail to respond favorably to conservative therapy. Surgical intervention in severe carpal flexural deformities requires an approach to the palmar aspect of the carpus through the medial aspect of the carpal canal by a surgeon familiar with the anatomy. The tendons are retracted caudally and then the radiocarpal and middle carpal joint capsules are transected in an attempt to straighten the limb. If the limb can be straightened, placement in a bandage with a splint or cast follows. If extension cannot be achieved, euthanasia is recommended as the prognosis for a normal limb is poor.18

Surgical treatment of deformities affecting the fetlock joint is approached in a stepwise fashion. Foals with congenital contractures often respond favorably to inferior check ligament desmotomy. Desmotomy of the superior check ligament may result in further improvement if necessary and can be completed during the same anesthetic. The degree of extension achieved with these desmotomies should be evaluated at the time of surgery, as it may be necessary in severe cases to proceed with severing the superficial digital flexor tendon or suspensory ligament or its branches.9

The tautest structure is severed first and then the foal recovered. Additional structures should be cut one at a time in subsequent surgeries, allowing sufficient time for observation of improvement. Arthrodesis of the metacarpophalangeal joint can be pursued in those foals with marked flexion and abnormal joint anatomy.19 Pasture soundness can be obtained.

Most distal interphalangeal joint flexural deformities respond to desmotomy of the inferior check ligament.8,9 Success is best achieved by combining this with use of orthopedic shoeing. In foals with a hoof ground angle greater than 90° that fail to improve following inferior check ligament desmotomy may require deep digital flexor tenotomy to achieve improvement.8,9,20 The tendon can be transected either at the level of the midcannon or at midpastern within the tendon sheath. In foals, both may result in a cosmetic and athletic outcome.9

In severe cases, corrective farriery can be an important component to the treatment of hyperextension of the digit.21 Farriery treatment consists of trimming the heel to elongate the weight-bearing surface and to give a flat surface on which the foal can bear weight. In mild cases of flexor tendon laxity, this will reduce the foal’s tendency to rock back onto its heel bulbs. For more severe cases, a caudal heel extension is necessary (Figure 9-8).

Selection of an appropriate extension will depend upon the materials that one has available. Ideally the extension should extend one to two inches behind the heel bulbs, and it should be made of material strong enough not to bend during weight bearing. The width should be similar to that of the foot. Curtis and Stoneham described the use of 5- to 7-mm-thick aluminum plating, but aluminum or steel hinges may be more readily obtainable.3,22 The aluminum is bent to extend partway up the dorsum of the foot and then along the sole of the foot. Application of the rigid extension to the hoof is facilitated with the use of hoof repair composite with or without fiberglass strengthening cloth incorporated in it. Taping with elastic tape or duct tape may also be used, but generally results in the extension becoming loose and ineffective. Custom glue-on shoes (Baby Glu, Mustad, Inc.) may be devised. However, the need to use them has decreased with the available hoof wall composites. In the neonate, nailed-on or wired-on shoes can be problematic as there is little hoof wall to safely nail to.22 Shoes attached in this manner often pulled off because of the softness of the hoof wall.

If caudal heel extensions are necessary on the forefeet, the length of the extension versus the risk of the foal overreaching with the hindlimb and removing the extension will need to be evaluated on an individual case basis. It may also be necessary to pad or bandage these forelimb caudal extensions so that they do not result in injury. Exercise will also hasten the correction.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories should be used judiciously during the correction of congenital flexural deformities. Invasive as well as conservative treatments may result in pain, as shortened musculotendinous units, ligaments, and joint capsule is stretched.1,8,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree