8 THE PELVIS (INCLUDING THE SPINE)

Clinical importance of the pelvis

Examination of the pelvis by rectal examination is not so easy in the horse as in the ox because the rectum is friable and easily torn. It can be used to evaluate inguinal hernias and cryptorchidism (undescended testis). If a stallion has colic, it can be used to investigate whether there is an incarceration of the intestine in the inguinal canal. The superficial inguinal ring is located 6–8 cm cranial to the iliopectineal eminence of the pubis and 10–12 cm lateral to the midline. The perineal region is a favoured area for the occurrence of melanoma in grey horses.

Castration of the stallion (also known as gelding) is one of the most common operations carried out in equine practice and is usually carried out to prevent male behaviour, rather than for medical or surgical reasons. The exception to this is for the horse that has an undescended testis (cryptorchid). There are open and closed techniques for castration. The operation can be carried out in the field, in the standing position, or in lateral recumbency. The operation can be followed by a variety of complications (infection, haemorrhage, swellings, septicaemia, tetanus, schirrhous cord, hydrocoele, penile prolapse, evisceration, and furunculosis) so care must be taken with hygiene. In the cryptorchid horse (‘rig’) the testis and epididymis fail to descend into the scrotum. In half of these cases, the testis is retained in the abdomen (usually near the deep inguinal ring) and the vaginal process is absent, or short (containing only the tail of the epididymis). In the other cases the testis lies in the inguinal region or canal. It may lie superficial to the superficial inguinal ring of the external abdominal oblique muscle, but it may not be palpable externally. In this position it will be lying between the origin of the lateral scrotal lamina from the dorsolateral edge of the ring (abdominal tendon of the external abdominal oblique muscle) and the origin of the medial scrotal lamina from the yellow elastic lamina medial to the ring. The cryptorchid testis in the inguinal position is usually much smaller than the descended testis, and the scrotum may be poorly developed. In most cases it can be removed by surgery in the inguinal region but some cases require a paramedian abdominal incision.

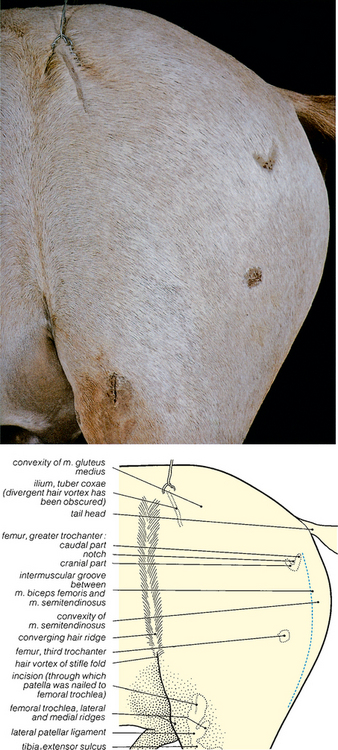

Fig. 8.1 Surface features of the pelvic and femoral regions of the gelding: left lateral view. The palpable bony features have been shaved. The rounded conformation of the gluteal musculature obscures the sacral tuberosity of the ilium in this horizontal lateral view, and the ischiatic tuberosity is similarly obscured by the semitendinosus muscle (see Fig. 8.3). The deep intermuscular groove between the biceps femoris and semitendinosus muscles (so-called ‘poverty line’) is much less conspicuous after embalming; in emaciated horses it is very prominent.

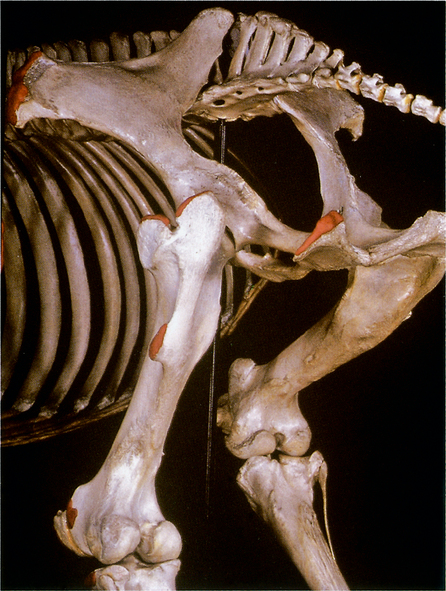

Fig. 8.2 Bones of the pelvic, femoral and stifle regions: left lateral view. The bony features shown in Fig. 8.1 are coloured red.

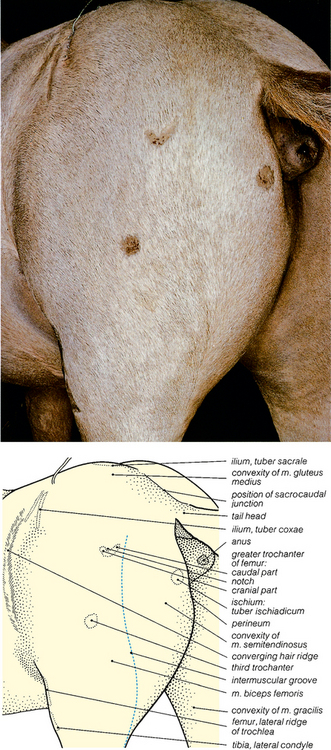

Fig. 8.3 Surface features of the pelvic and femoral regions of the gelding: left caudolateral view. The positions of the sacral and caudal vertebrae are shown in Figs. 8.93 and 8.95.

Fig. 8.4 Bones of the pelvic, femoral and stifle regions: left caudolateral view. The bony features shown in Fig. 8.3 are coloured red, except for the tuber sacrale.

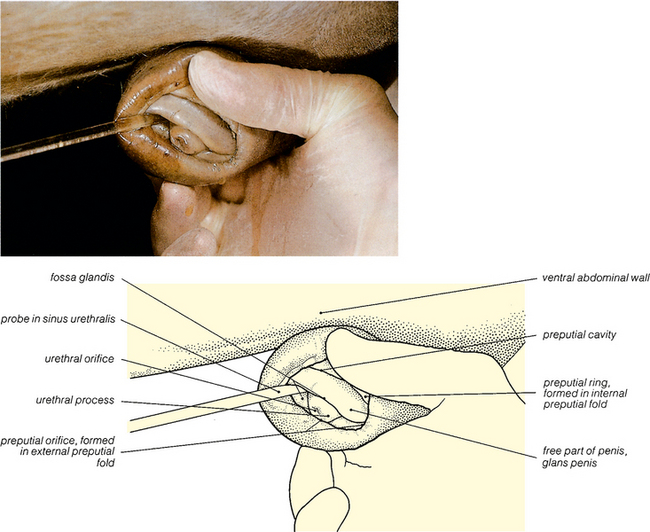

Fig. 8.5 Surface features of the penis and prepuce of the gelding: left lateral view. At birth, the free part of the penis is adherent to the internal lamina of the prepuce (see Fig. 8.47) but this adherence rapidly breaks down (Figs. 8.48 to 8.53) and in geldings and stallions the free part of the penis is separated from the prepuce by the preputial cavity. The urethral process is enclosed by a narrow cavity, the fossa glandis; the sinus urethralis is a dorsal enlargement of this fossa, and its position is indicated by the probe.

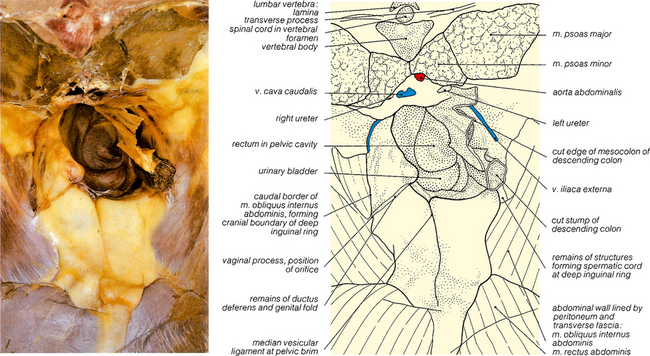

Fig. 8.6 The pelvic inlet of the gelding: cranial view. The trunk has been cut through at the level of the third lumbar vertebra after removal of the abdominal viscera. The urinary bladder is empty and entirely pelvic in position. The peritoneum of the inguinal regions remains intact. The corresponding region of the mare is shown in Fig. 5.45 (non-pregnant) and Fig. 8.57.

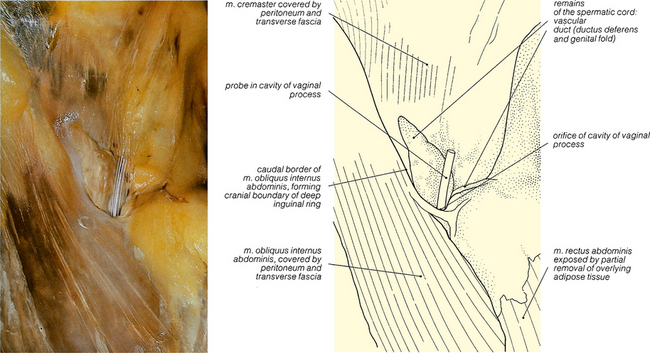

Fig. 8.7 The right inguinal canal of the gelding: cranial view. This is a closer view of a part of the specimen shown in Fig. 8.6, at a slightly later stage in the dissection. After castration, the components of the spermatic cord atrophy. A probe has been inserted into the persistent and still patent orifice leading to the cavity of the remaining stump of the vaginal process.