7 THE FOOT

Clinical importance of the foot

There are several types of fracture (#) of the pedal bone (distal phalanx):

The joints of the manus and pes of the older horse are also subjected to a wide range of abnormalities. Sub-luxations occur and must be repaired, but they have a very poor prognosis. Luxations occur in the proximal (PIP) and the distal (DIP) interphalangeal joints. Angular deformity (joint laxity) of the fetlock is also a possibility. This, and a similar interphalangeal disorder, have a poor prognosis. Flexural deformity of the fetlock is either congenital or acquired. It may be due to relative shortening of the musculo-tendinous part of the superficial digital flexor muscle, the deep digital flexor muscle, or the sesamoidean ligaments. Traumatic and degenerative arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP or pastern joint) and distal interphalangeal joint (DIP or coffin joint) has been described, and infectious arthritis of the joint is also known.

Several nerve blocks are used to localise the site of lameness in the manus or pes. Perineural analgesia of the distal digital region can be achieved by blocking the lateral and medial palmar/plantar nerves at the level of the middle phalanx. The needle is inserted subcutaneously over the palpable neurovascular bundle, just proximal to the ungular cartilage of the distal phalanx on each side. This is the Palmar/Plantar digital nerve block. These nerves can be blocked at a more proximal level by inserting the needle subcutaneously over the palpable neurovascular bundle, on the abaxial surface of the lateral and then the medial proximal sesamoid bone. This is the Abaxial sesamoid nerve block.

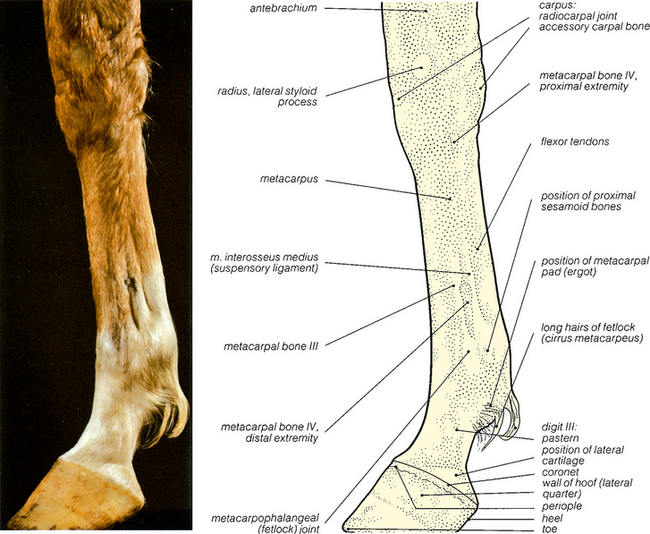

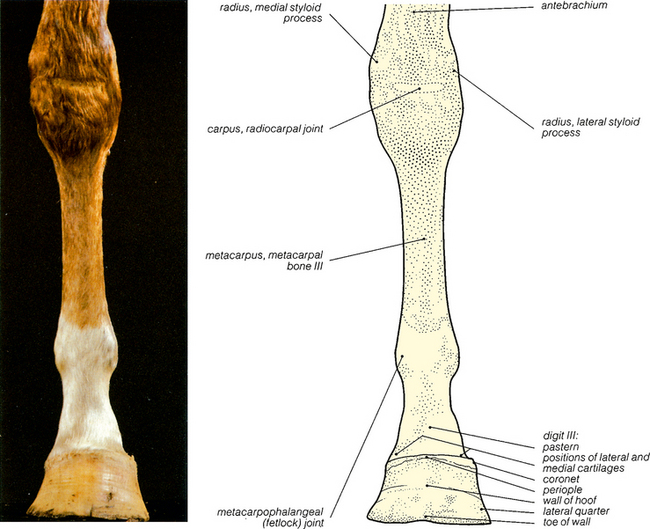

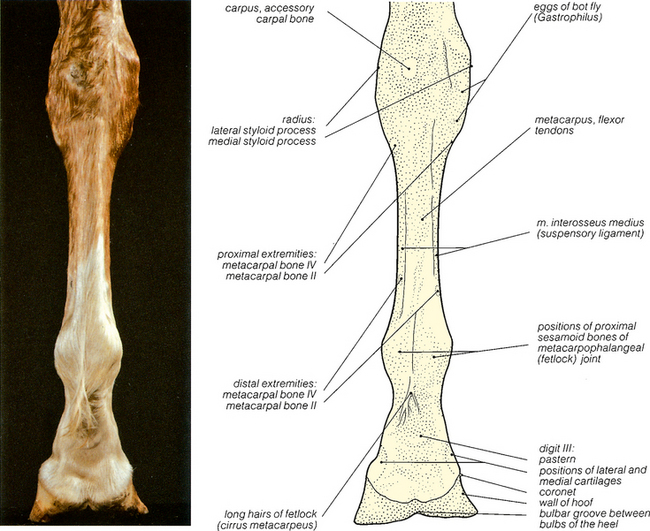

Fig. 7.1 Surface features of the left manus: cranial view. Figs. 7.3, 7.5 and 7.7 show further views of this specimen. Palpable features have been shaved. Figs. 7.2, 7.4, 7.6 and 7.8 show the bones of the region. Fig. 7.9 shows the solar surfaces of the hoof.

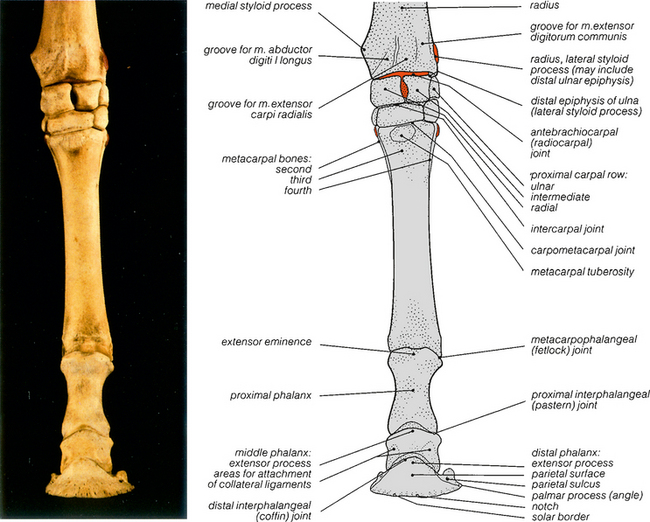

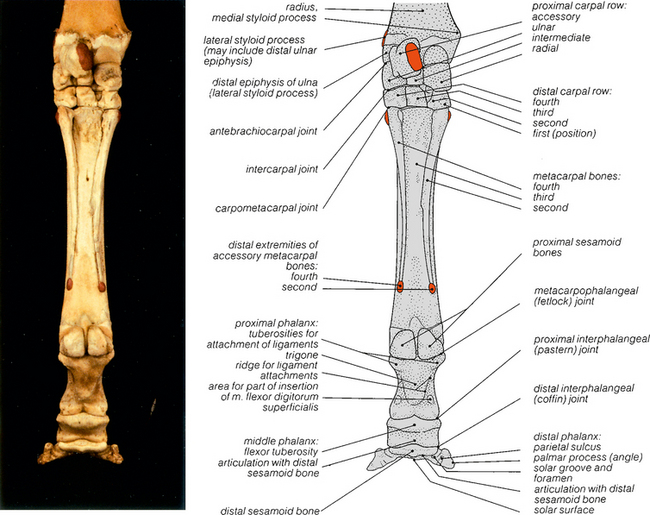

Fig. 7.2 The bones of the left manus: cranial view. The prominences shaved in Fig. 7.1 have been coloured red, except for the salient medial styloid process. For a comment on the lateral styloid process, see Fig. 7.4.

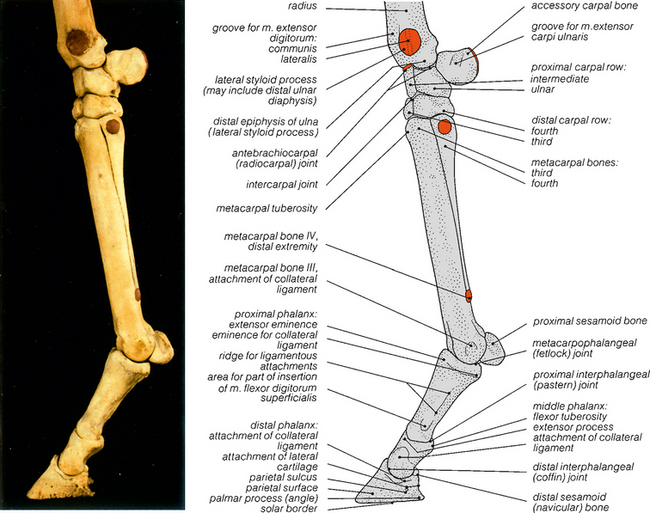

Fig. 7.4 The bones of the left manus: lateral view. The prominences shaved in Fig. 7.3 have been coloured red. The distal epiphysis of the ulna fuses with that of the radius at about 1 year, to form the lateral articular condyle. The prominence just proximal to it is probably of diaphyseal origin, but it is commonly called the lateral styloid process of the radius.

Fig. 7.5 Surface features of the left manus: caudal view. At the palmar aspect of the fetlock, the spur-like keratinised ergot (metacarpal pad) lies hidden in the long fetlock hairs (cirrus metacarpeus); it is visible in Fig. 7.9. The eggs of the bot fly, Gastrophilus, are adherent to the hairs on the medial aspect of the carpus; this horse was killed in September.

Fig. 7.6 The bones of the left manus: caudal view. The parts shaved in Fig. 7.5 have been coloured red, except for the salient medial styloid process. The inconstant and variable first carpal bone was not present on this skeleton, but its position is indicated in the drawing.