CHAPTER 6 Ayurvedic Veterinary Medicine: Principles and Practices

INTRODUCTION TO AYURVEDIC VETERINARY MEDICINE

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ethnomedical, or “traditional” medical practices are still used by 85% of people in developing countries as their first line of medical “defense” (WHO, 1988). The Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) advocates the use of traditional medical practices for animal treatment in developing countries (Anjaria, 1984).

Ayurvedic diagnosis is made after three sources of patient information are considered:

It is important to stress again that a veterinarian need not adopt any or all of the principles and practices of Ayurvedic medicine to benefit from its use. Many Ayurvedic herbs are unique, coming from the very diverse panoply of ecosystems found in India. Many herbs from the Indian subcontinent contain phytochemicals that are not found in the herbs of the Western tradition. This is due, in part, to the more tropical climate and richly volcanic soil specific to the Himalayans and other mountain ranges in India. One such herb that is indigenous to India is the tree named Boswellia serrata, from which the oleo-resin boswellia is extracted. Another unique herbal from India is shilajeet, which is an organic exudate derived from a specific geologic formation that incorporates layers of organic sediment.

HISTORY OF AYURVEDA

India possesses one of the oldest organized systems of medicine. Its roots can be traced back to the remote and distant past of human prehistory. Elements of Ayurvedic medicine can be found at the roots of nearly all traditional and modern systems of medicine in the world. Early written accounts describing the medicinal use of plants are found in the ancient Vedic texts. These writings originated in the period circa 3147 bc (Anjaria, 2002).

The Indian mythologic epic poem, “The Ramayana” (Ramayana, 1958), described Vaid Sushena from Sri Lanka treating the unconsciousness of Laxmanji with the use of a specific herb (not mentioned). Herbal treatments for animals are also emphasized in this text, dating back to circa 4000 bc (Anjaria, 2002). The Mahabharata (∼3000 bc), another Indian classic (Mahabarat, 1958), includes a story of an animal trainer and a caretaker. Elsewhere in this ancient text are descriptions of “noted animal physicians.” This book contains one of the earliest written records documenting the practice of veterinary medicine in ancient history. Somavanshi has reviewed the ethnoveterinary resources of ancient India. This review reports the availability and sources of ancient Indian literature from different libraries and documentation centers in India (Somavanshi, 1998).

Chapters that discuss animal husbandry practices appear in Skanda Purana, Devi Purana, and other lesser known texts. The horse played an important role in the lives of ancient people; because of this, equine ethnoveterinary medicine attained a glorified status in ancient India. Famous veterinarians were described: Palkapya, around 1000 bc, and Shalihotra, around 2350 bc, specialized in the treatment of horses and elephants. Elephants were also very important because of their role in ancient Indian culture as beasts of burden. The science of elephant medicine is detailed in many early Indian texts (Anjaria, 2002).

Shalihotra is reported to have written the first book on veterinary treatments in Sanskrit. This text was called The Shalihotra and is considered to be the first book ever written to describe specific techniques in veterinary medicine, including the use of indigenous herbs in the treatment of working animals. Another text attributed to Shalihotra is Ashva-Ayurveda, which discussed treatment of the horse. Shalihotra is considered to be historically the first true veterinarian because of his contributions to the science of veterinary medicine (Anjaria, 2002).

A number of other ancient Indian texts not as well known as the texts previously discussed also contain chapters on veterinary medicine. Prescriptions for the treatment of animals have been detailed in these texts as well (Anjaria, 2002). Charak and Sushruta, 1220 bc and 1356 bc, respectively, compiled their observations on indigenous and herbal therapy as the Charak Samhita (medicine) and the Sushruta Samhita (surgery) (Charak Samhita, 1941). Mrig Ayurveda is another ancient text that describes the medical treatment of animals; it is sometimes loosely translated as Animal Ayurveda. A synonym of Mrig is Pashu, which often follows Mrig in parentheses. Mrig (Pashu) Ayurveda is considered to be a special branch of Ayurveda. This ancient text is stored in the Library of Gujarat Ayurveda University in Jamnagar, India. Hasti Ayurveda is a comprehensive text that contains material devoted to medicine for elephants (Anand, 1894).

The first veterinary hospital was built by King Ashoka (300 bc). He also developed operational protocols for veterinary hospitals regarding the use of botanical medicinals (Anjaria, 2002). Historically, Ayurvedic medicine expanded its influence into Asia, contributing to the development of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Buddhist monks practiced Ayurveda and planted Ayurvedic herb gardens along their peripatetic routes while spreading Buddhist thought and political influence throughout all the far corners of Asia. In this way, Ayurveda spread to Sri Lanka, Nepal, Tibet, Mongolia, Russia, China, Korea, Japan, and other parts of Southeast Asia.

Some authorities believe that many Greek and post-classical philosophers like Paracelsus, Hippocrates, and Pythagoras may have actually visited India and the East and learned from Ayurvedic and other Eastern teachings; they then brought the medicines they found there back to Greece. The great Hellenic physician Dioscorides mentions many Indian plants in his work, including the use of datura for asthma, and nux vomica for paralysis and dyspepsia. The Roman Empire also relied heavily upon Indian medicines. Imports of ginger and other spices from India were so large that the famous Roman herbalist, Pliny, complained about the heavy drain of Roman gold for the purchase of Indian herbal medicines and spices and the effects of this on the Roman economy (Kapoor, 1990).

PHILOSOPHIES UNDERLYING AYURVEDA

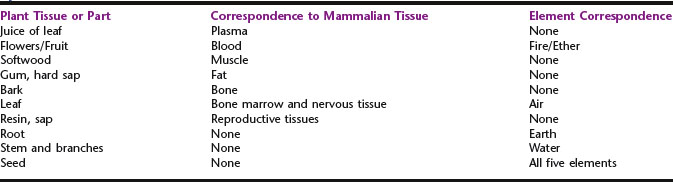

Seven types of vital tissues (Dhatus) in the bodies of humans and animals are derived from food. These tissues include Plasma, Blood, Muscle, Fat, Bone, Bone Marrow and Nervous Tissue, and Reproductive Tissue. Plants have tissue types that correspond to these animal tissues. Each plant tissue nourishes its corresponding animal tissue. It is thought that each tissue nourishes the next tissue on the list (Table 6-1). Thus, the juice of the leaf nourishes the flowers and fruit; the flowers and fruit nourish the softwood, and so forth. Plant parts also relate to the five elements. These relationships are also outlined in Table 6-1.

TABLE 6-1 Ayurvedic Elements Associated With Mammalian and Plant Tissues

| Plant Tissue or Part | Correspondence to Mammalian Tissue | Element Correspondence |

|---|---|---|

| Juice of leaf | Plasma | None |

| Flowers/Fruit | Blood | Fire/Ether |

| Softwood | Muscle | None |

| Gum, hard sap | Fat | None |

| Bark | Bone | None |

| Leaf | Bone marrow and nervous tissue | Air |

| Resin, sap | Reproductive tissues | None |

| Root | None | Earth |

| Stem and branches | None | Water |

| Seed | None | All five elements |

THE TRIDOSHA

Critical to an understanding of Ayurvedic principles is the concept of the three Doshas (the group is known as the Tridosha) (Table 6-2), which describe the three basic characteristics found in all livings things from both Animal and Plant Kingdoms. In Sanskrit, Dosha means, literally, “fault or error, a thing which can go wrong” (Svoboda, 1995). The three Doshas are described by the elements and energies inherent in each tendency. These qualities include factors like temperature, moisture, weight, and texture. The Tridosha represents three primal metabolic tendencies in the living organism. Each individual, whether human, plant, or animal, embodies one or a combination of two of the Doshas.

This embodiment is considered to be an organism’s individual constitution. Balance among the members of the Tridosha results in health and homeostasis. Disease results from an imbalance among the three Doshas. Individual constitution also represents the type of disease to which an individual is most prone. Disease conditions that differ in nature from the individual are usually easy to treat. When the disease is the same Dosha as the individual, it is more difficult to treat because the constitution of the individual reinforces the disease pattern (Frawley, 1988).

The first Dosha is named Vata, which means “wind.” Vata is dry and cold. It is the principle of kinetic energy and corresponds most closely to the TCM concept of Qi (Svoboda, 1995). Vata is associated with the mental phenomena of enthusiasm and concentration. It is concerned with processes that are activating and dynamic in nature. It is derived from the elements Ether and Air. Vata is the most powerful of the Doshas and is considered to be the “Life Force.”

The second Dosha, Pitta, or bile, is derived from Fire and an aspect of Water. It is the principle of biotransformation and balance and is the cause of all metabolic processes in the body. It rules all of the enzymes and hormones in the body. It is most closely associated with the TCM concept of Yang. Pitta is associated with the mental processes of intellect and clear and focused concentration. Pitta governs the activities of the endocrine organs. It governs body heat, temperature (thermogenesis, thermal homeostasis), and all chemical reactions (Svoboda, 1995).

Pitta maintains digestive and glandular secretions, including digestive enzymes and bile. It is responsible for digestion, metabolism, pigmentation, hunger, thirst, sight, courage, and mental activity. Its location in the body is between the navel and the chest in the stomach, small intestines, liver, spleen, skin, and blood. Its primary location in the body though is the small intestines and, to a lesser extent, the stomach. When Pitta is out of balance, its primary manifestation is acid and bile, leading to inflammation. Humans with Pitta pathology complain of a burning sensation in the stomach or liver. Animals with a Pitta constitution have a mesomorphic constitution and a tendency toward “hot” behavior, such as might be found in a Rottweiler, Chow Chow, or Pit Bull terrier (Sodhi, 2003).

Without any one of these qualities, life cannot exist. Seven combinations of the three Doshas in turn become the seven possible constitutions (Boxes 6-1 and 6-2).

BOX 6-1 The Seven Constitutions From the Tridosha

| Vata | Anxious, fearful, light and “airy”; ectomorphic; prone to Vata diseases |

| Pitta | Aggressive and impatient, “fiery” and hot headed; mesomorphic; prone to Pitta diseases |

| Kapha | Stable and entrenched, heavy, wet and “earthy;” endomorphic; prone to Kapha diseases |

| Vata-Pitta | Blend of Vata/Pitta traits |

| Pitta-Kapha | Blend of Pitta/Kapha traits |

| Vata-Kapha | Blend of Vata/Kapha traits |

| Sama | Balanced Vata/Kapha/Pitta (rare) |

BOX 6-2 Seasons and Times According to Tridosha

Vata

Season: Fall (September—November) Avoid Vata-promoting foods during Vata months

Pitta

Season: Summer (June-August) Avoid Pitta-promoting foods during Pitta months

The diagnosis of Ama is made on the basis of the following signs:

Just as there are channels, meridians, or vessels in TCM, Ayurveda has the Srotas. These are the subtle body channels through which certain types of energy move through the organism. Srotas are the energetic equivalents of physical structures such as nerves and blood vessels. This makes them responsible for the transportation of energies through the entire body; thus, they serve an important nourishing function.

According to Ayurvedic thought, the three categories of disease include the following (Zysk, 1996):

AYURVEDIC DIAGNOSTIC PRACTICES

Ayurveda has a well-established system of diagnosis, similar in some respects to TCM. An initial examination is made using visual observation, palpation, and questioning. The detailed examination determines the patient’s physical constitution type and mental status. The diagnostician tries to discover any indications of imbalances or abnormalities in the patient. Susruta (cited in Frawley, 1988) writes as follows:

Pulses are considered to provide important information to assist the clinician in his or her quest to understand the patient and gain control over disease. Pulse taking makes use of the physical interaction of physician and patient. For the veterinarian, whose patient does not speak of the condition, pulse taking can provide another dimension for gaining insight into the animal and its condition.

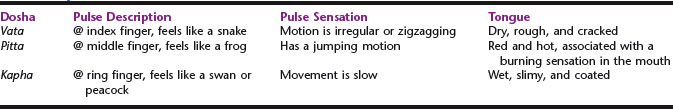

Pulse diagnosis is used by most Ayurvedic practitioners. It was introduced as an Ayurvedic diagnostic around the 9th century ad. For the Ayurvedic pulse, the hands are positioned similarly to TCM positioning. In dogs and cats, the femoral artery is palpated. The radial artery of the right hand is palpated for human males, and the left hand is palpated for females. In Ayurvedic tradition, palpation of a pulse wave at the index finger that feels like a snake indicates Vata. If the pulse feels like a frog at the middle finger, this indicates Pitta. If the pulse wave at the ring finger feels like the movement of a swan or a peacock, then the predominant dosha is Kapha. In other words, pulse quality variation can help the clinician to determine constitution. In a similar way, femoral pulse variation in animals can be useful to a skilled Ayurvedic practitioner for determining constitutional pathology (Table 6-3).

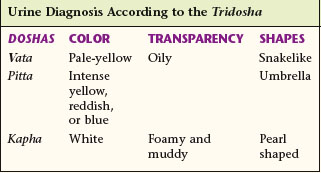

Additional diagnostic parameters are gathered by the practitioner through detailed observations of the patient and examination of the urine. Observations of the patient’s demeanor in the examination room helps with the practitioner’s diagnosis. Consideration is given to patient body type, ambulation—both in and out of the examination room—and the appearance of patient skin, haircoat, pads, nails, and hooves. Also of importance to a thorough diagnosis is the nature, quantity, and quality of vocalizations. Urine examination involves the free-catch collection of the first urine mid stream in a clear glass jar. After sunrise, the urine is examined for color and degree of transparency (Box 6-3).

After visual inspection, a few drops of sesame oil are placed in the urine and examined in the sunlight. Shape, movement, and diffusion of the oil in the urine are prognosticators. The drops will form different shapes, giving an indication of which Doshas are involved. Visual examination of various parts of the body aid the Ayurvedic veterinarian in diagnosis. Tongue, skin, nails, and other physical features point out which Doshas are most involved in the patient’s diagnosis. The physical condition of the body can be related to the Tridosha (Box 6-4).

BOX 6-4 Tridosha Diagnosis Based on Physical Characteristics

| TRIDOSHA | PHYSICAL CONDITION OF THE BODY |

|---|---|

| Vata | Coldness, dryness, roughness, and cracking |

| Pitta | Hotness and redness |

| Kapha | Wetness, whiteness, and coldness |

Three types of prognoses are recognized in Ayurvedic medicine:

The ability to cure a patient is also dependent on the season in which he or she is being treated. Thus, if the disease, constitution, and season correspond to the same Dosha, then the disease is nearly impossible to cure (Zysk, 1996). Treatment in Ayurveda is dependent on the Tridosha of the patient. The patient’s constitution is taken into account, and therapy is directed toward balancing the excesses (reducing excess first, then supporting deficiency). This balance is achieved through a combination of dietary therapy, lifestyle alterations, detoxification, and herbal therapies.

PRINCIPLES OF AYURVEDIC HERBAL THERAPY

Ayurveda is a “holographic” and “holistic” system (Svoboda, 1995). It is stated in the Charaka Samhita that

This macrocosm/microcosm relationship can also be seen in the way that plants are categorized in Ayurveda according to the seven bodily tissues (Dhatus). A correspondence is noted between the tissues of the Plant Kingdom and the tissues of the Animal Kingdom. In Box 6-5, the plant tissue is listed to the right of the animal tissue it is associated with. The tissues of plants have activity on the tissues of the mammalian body to which they correspond. Of all plants, the tree is considered to be the ultimate expression of the Plant Kingdom, in the same way that the human being is considered to be the ultimate expression of the Animal Kingdom (Frawley, 1988).

BOX 6-5 Animal–Plant Tissue Correspondence

| ANIMAL TISSUE | PLANT TISSUE |

|---|---|

| Plasma | Juice of leaf |

| Blood | Resin, sap |

| Muscle | Softwood |

| Fat | Gum, hard sap |

| Bone | Bark |

| Marrow and nerve tissue | Leaf |

| Reproductive tissue | Flowers and fruit |

Ayurvedic Plant Properties

Plant properties are defined by Ayurveda according to their energetics. These energetics are determined by the herb’s taste, heating or cooling nature, postdigestion effects, and special potency effect on target organs. From these selection criteria, the individualized herbal remedy is chosen to match or balance the Ayurvedic diagnosis that reflects the characteristics specific to the Ayurvedic patient (Sodhi, 2003).

Ayurvedic Herbs Grouped by Therapeutic Category

The following therapeutic categories are common to all ethnomedical systems of herbal medicine. Examples of Ayurvedic herbs are provided in each category (Sodhi, 2003).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree