5 THE ABDOMEN

Clinical importance of the abdomen

Enteritis is not common in the horse but there is, on occasion, an acute severe enteritis in horses associated with clostridial infections. It causes an acute colic and is often diagnosed only at surgery or post-mortem examination. There are up to 10 parasites that may live in the large bowel and cause irritation which may lead to diarrhoea. Severe diarrhoea, with irritation and constant straining, may lead to intussusception. Sudden dietary changes and parasitic infestation are usually a cause of this condition. There is also a real possibility of salmonellosis in any horse that is stressed or has been subjected to surgery. Several other conditions may also cause acute enteritis such as Potomac horse fever in certain parts of the world. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease can also occur. It usually involves internal parasites but also may involve strangles, Rhodococcus equi or even M. paratuberculosis. A naso-gastric (stomach) tube can be used to deliver large volumes of oral rehydration therapy.

Clinical considerations for the spine in the abdominal region are dealt with in the section on the spine in Chapter 8 (p. 269).

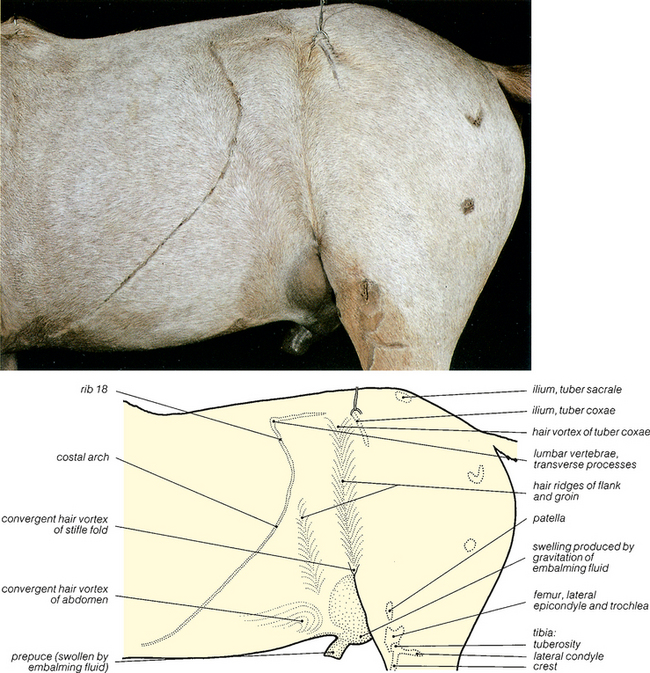

Fig. 5.1 Surface features of the abdomen: left lateral view. The hair has been shaved over the palpable bony prominences. The umbilicus lies in the median plane, just cranial to the prepuce, and its position in the female is shown in Fig. 5.55.

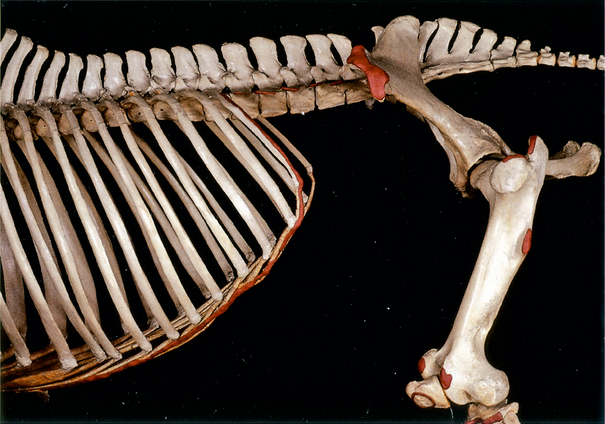

Fig. 5.2 Bones related to the abdomen: left lateral view. The palpable bony prominences shown in Fig. 5.1 are coloured red, except for the tuber sacrale.

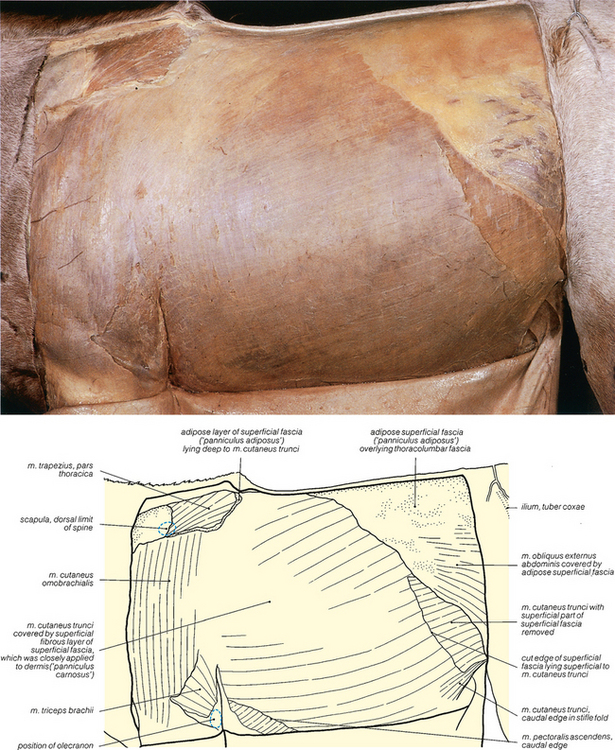

Fig. 5.3 The cutaneous muscle of the trunk: left lateral view. The muscle lies in the superficial fascia; superficially it is closely adherent to the dermis and forms the ‘panniculus carnosus’. Deep to it, the superficial fascia contains extensive fat deposits (‘panniculus adiposus’). The cutaneous nerves are shown in Figs. 5.4 and 5.10. See also Fig. 5.9.

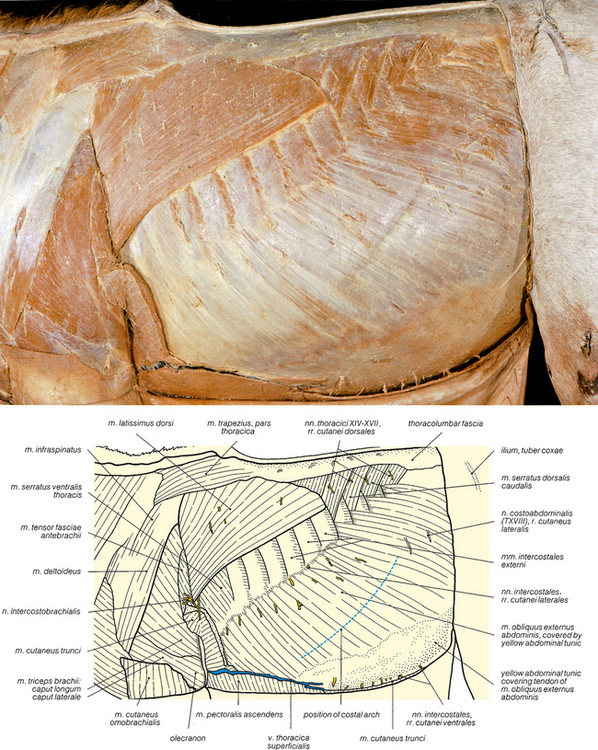

Fig. 5.4 The external oblique abdominal muscle and cutaneous nerves of the thoracic and abdominal wall: left lateral view. The cutaneous muscles have been removed. Further details of the nerves are shown in Fig. 5.10.