4 THE THORAX

Clinical importance of the thorax

There are various cardiac complaints in the horse. Congestive heart failure can be left-sided or right-sided. Pericarditis, pericardial effusions, and myocarditis (ionophore toxicity) occur. Aortic root rupture results in sudden death with massive haemorrhage into the thoracic cavity. Many abnormal sounds may be heard in the examination of the heart. They include cardiac murmurs which can indicate stenosis of valves, incompetence of valves, shunts, and pre-systolic and systolic murmurs. Ectopic beats also occur in some horses. Disorders of cardiac rhythms include sinus arrhythmia, sinus tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, ventricular fibrillation, atrio-ventricular block and sino-atrial block. Congenital heart defects do occur rarely in foals. These include ventral septal defects, persistent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, myocarditis and fibrocarditis.

Clinical considerations for the spine in the thoracic region are dealt with in the section on the spine in Chapter 8 (p. 269).

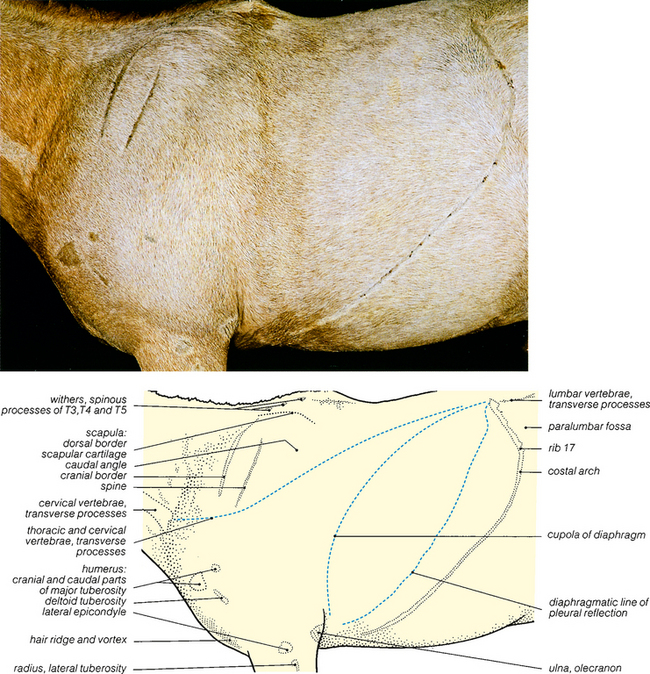

Fig. 4.1 Surface features of the neck, shoulder and thorax: left lateral view. The hair over the palpable surface features was shaved before embalming commenced. Rib 18 was small and not clearly palpable. The surface projections of the thoracic and cervical vertebrae, cupola of the diaphragm and diaphragmatic line of pleural reflection are based on the dissections shown in Figs. 4.17 and 4.22.

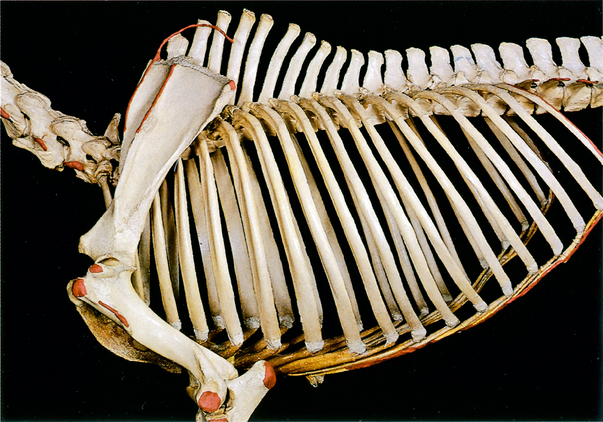

Fig. 4.2 Skeleton of proximal forelimb and thorax: left lateral view. The palpable features shown in Fig. 4.1 are coloured red except for the spinous processes at the withers. Note that in this articulated skeleton rib 18 is large. In the dissected specimen this rib was small (see Fig. 4.9) and the last distinctly palpable rib was rib 17.

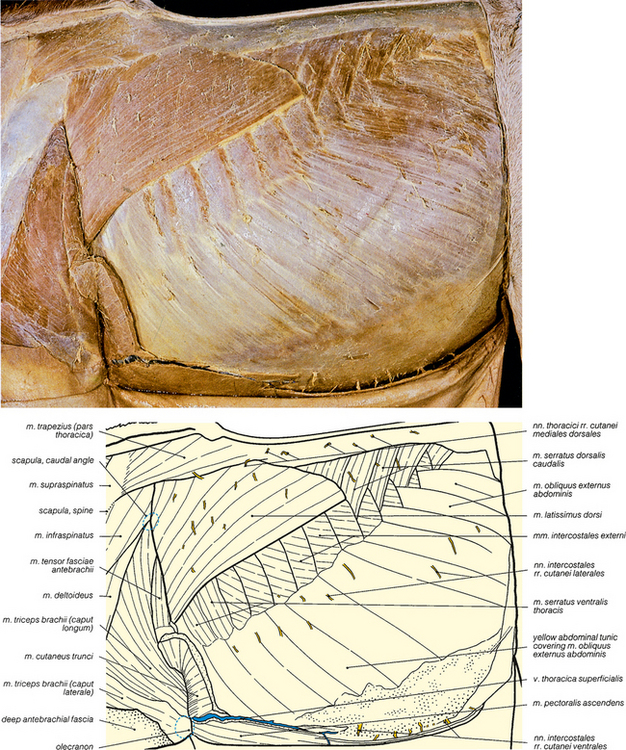

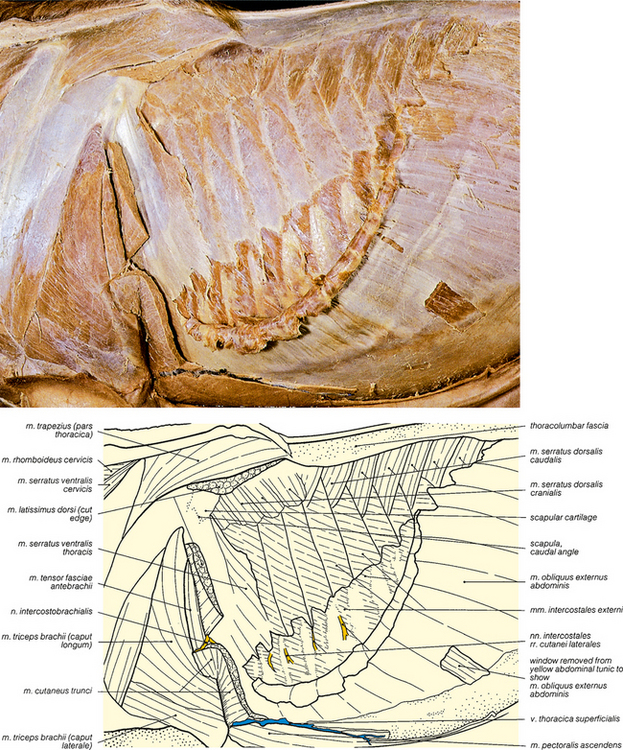

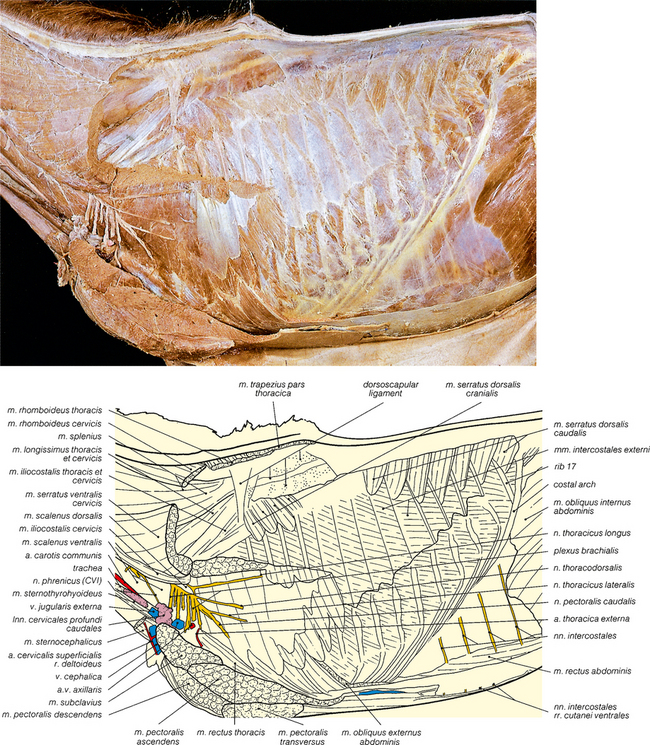

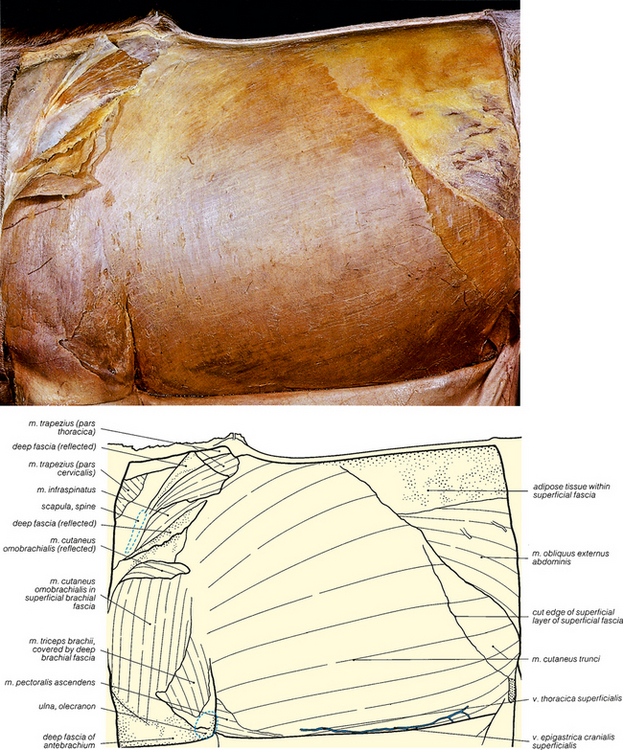

Fig. 4.3 The cutaneous muscles and superficial fascia of the trunk: left lateral view. The skin has been carefully removed to display the cutaneous muscles which lie just beneath the dermis, within the superficial fascia. An earlier stage of the dissection is shown in Fig. 5.3.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>