CHAPTER 4 The Roots of Veterinary Botanical Medicine

Today, veterinarians frequently study the names and properties of herbs, yet they may have little or no personal experience of the nature of the plant, its environment, its taste, and its properties. Theoretical knowledge is sterile compared with traditional herbalists’ approach of tasting each herb, experiencing its unique qualities, and discerning its properties. Herbalists like Shen Nong Dioscorides and many others learned from their direct experience; this is invaluable even today. Observing herbs and tasting them directly or by infusion, decoction, pills, or formulas is of great benefit, as is taking the herbs for a course of therapy to experience the effects. Herbalists who follow this path will know at a deep experiential level what it is they are prescribing.

Herbal medicine is one of the oldest forms of treatment known and used by all races and all peoples. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that botanical medicines are used by 70% of the world’s population (Eisenberg, 1998), and it is no surprise that people have used the same plant medicines for the animals in their care as long as animals have been associated with human life. Thus, the history of veterinary botanical medicine, the oldest form of veterinary medicine, has followed a parallel route alongside the evolution of human medicine for much of history. Indeed, herbal medicine itself has undergone a number of philosophical shifts over time, but from antiquity until now, it has remained fundamentally unchanged in tone. Herbal medicine is empiricist, holistic, and vitalist in orientation, and some herbalists argue that it should remain so, even as modern medicine tries to incorporate the use of herbs as “drugs” seeking the “active constituent.” This “scientism,” perhaps bordering on reductionism, is simply a new philosophy in the larger picture of herbal medicine.

ANTIQUITY

Evidence suggests that Ayurveda, developed in India, is perhaps the earliest medical system. The Rig veda, the oldest document of human knowledge, written between 4500 and 1600 bce, mentions the use of medicinal plants in the treatment of humans and animals. The “Nakul Samhita,” written during the same period, was perhaps the first treatise on the treatment of animals with herbs. Chapters dealing with animal husbandry like “Management and Feeding” appear in ancient books like Skandh Puran, Devi Puran, Harit, and others. Palkapya (1000 bc) and Shalihotra (2350 bc) were famous veterinarians who specialized in the treatment of elephants and horses (Unknown, 2004). King Asoka (274-236 bc) engaged people to grow herbs for use in the treatment of sick and aged animals (Haas, 1992). Medicines that are mentioned in early Ayuvedic texts (200 bc–ad 200) of Charaka Samhita include ricinus, pepper, lily, and valerian.

“According to Ayurveda, every human being is a creation of the cosmos, the pure cosmic consciousness, as two energies: male energy, called Purusha and female energy, Prakruti. Purusha is choiceless passive awareness, while Prakruti is choiceful active consciousness. Prakruti is the divine creative will…. The structural aspect of the body is made up of five elements, but the functional aspect of the body is governed by three biological humors [or doshas]. Ether and air together constitute vata; fire and water, pitta; and water and earth, kapha. Vata, pitta, and kapha are the three biological humors that are the three biological components of the organism. They govern psycho-biological changes in the body and physio-pathological changes too. Vata–pitta–kapha are present in every cell, tissue, and organ. In every person, they differ in permutations and combinations. [The balance in the doshas can be effected by] hereditary, congenital, internal, external trauma, seasonal, natural tendencies or habits, and supernatural factors.” (Lad, 1996)

The Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing describes for the first time the flavors (sour, salty, sweet, bitter, acrid/pungent), natures (cold, hot, warm, cool), functions, and indications for the herbs. Herbs were classified according to their efficacy and toxicity, and the terms sovereign (or king), minister, assistant, and envoy were described to define the function of an herb within a formula. According to the Ben Cao, “Medicinals should coordinate [with each other] in terms of yin and yang, like mother and child, or brothers…. to treat cold, one should use hot medicinals. To treat heat, one should use cold medicinals.” Shen Nong clearly tasted the herbs and fit their characteristics into the Tao, the philosophy that guided people’s understanding of their world. Herbs were tools that interacted with people to shift and balance their bodies back to health. An English language translation of the ancient Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing has been published (Yang, 1997).

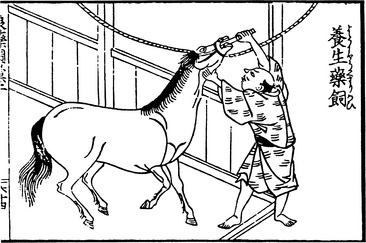

The earliest Chinese medical practitioners treated both people and animals until the Zhou dynasty (1122-770 bc), when veterinary medicine became a separate branch of traditional Chinese medicine (Schoen, 1994), and in China, the first mention of diseases and treatments of horses appeared in writings of the Shang Dynasty (1766-1027 bc). One of the first texts in Chinese veterinary medicine was Bai Le’s Canon of Veterinary Medicine, written by Sun Yang in approximately 650 ad (Figure 4-1).

In Mesopotamia, the Sumerians used cuneiform written language from about 3500 bc. The earliest extant clay tablet from Sumeria dates from about 2100 bc; it contains 15 medical prescriptions and mentions 120 mineral drugs and 250 plant-derived medicines. These included asafetida, calamus, crocus, cannabis, castor, galbanum, glycyrrhiza, hellebore, mandragon, menthe, myrrh, opium, turpentine, styrax, and thyme. The largest surviving medical treatise is from about 1600 bc; it is entitled “Treatise of Medical Diagnoses and Prognoses.” Although the names of the medicines used then do not translate well, it is probable that milk, snakeskin, turtleshell, cassia, thyme, willow, fir, myrtle, and dates were also used (Janick, 2002). The Code of Hammurabi (circa 1780 bc), another famous document arising from Babylonian society, discussed treatments of animals, costs of treatments, and penalties for mistreatment and errors (Swabe, 1999).

The Edwin Smith Papyrus (found in Egypt and preserved at the New York Academy of Medicine) dates from 1700 bce. These scrolls include a surprisingly accurate description of the circulatory system, noting the central role of the heart and the existence of blood vessels throughout the body. They describe the use of herbs such as senna, honey, thyme, juniper, pomegranate root, henbane, flax, oakgall, pinetar, bayberry, ammi, alkanet, aloe, cedar, caraway, coriander, cyperus, elderberry, fennel, garlic, wild lettuce, myrrh, nasturtium, onion, peppermint, papyrus, poppy, saffron, watermelon, and wheat. The Ebers Papyrus (now in University Library at Leipzig) dates from about 1500 bc and contains more than 800 prescriptions. Some of these are very complicated, containing such ingredients as opium, hellebore, salts of lead and copper, and blood, excreta, and viscera of animals (Haas, 1999). Many more of the ancient scrolls were housed in the Library of Alexandria, which was destroyed by fire in 47 bce. However, early evidence of veterinary herbal medicine is found in ancient Egyptian parchments such as the Kahun Veterinary Papyrus (dating around 1900 bc) (Karasszon, 1998), on which cattle feature prominently.

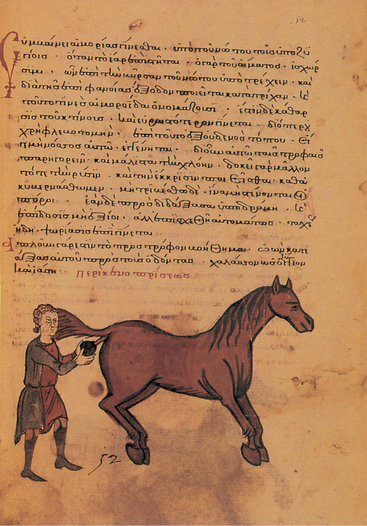

Ancient Greek and Roman societies began developments in veterinary medicine in similar, yet slightly different directions compared with the Egyptians. The “Hippiatrika” is one of the first documents we see that relates to Roman practitioners and their study of horses (Walker, 1991). “Hippiatros” was a term used in Greece around 500 bc to refer to horse doctors (Swabe, 1999). The horse was central in Greek and Roman society because members of society depended on it for military and trade functions. Earlier on (between 383 bc and 322 bc), Aristotle, sometimes called “the Father of Veterinary Medicine,” became very influential in Greek society. Physiology, comparative anatomy, and pathology were a few of the specialized areas that Aristotle discussed in his writings. He compared animal and human anatomy and physiology and disease in writings such as Historia Animalium, De Partibus Animalium, De Generatione Animalium, and Problematicum (Karasszon, 1998). Another important influence on both veterinary and herbal medicine was Hippocrates (460-377 bc). He wrote Corpus Hippocraticum, in which he described more than 200 plants, and he is credited with the development of the humoral theory (Figure 4-2).

HUMORAL THEORY

The rise of rationalism meant that doctors were now observing patients and reasoning toward a logical cure, just as the Chinese had done. Hippocrates reasoned that medicine could be applied without ritual because disease was a natural phenomenon and not a supernatural event. He argued that some acute diseases were self-limiting and should not necessarily be treated, and that diet and exercise were vital in preventing and treating conditions of the human body. The humoral theory remained very influential for more than a thousand years and was not seriously challenged until the 15th century. It is interesting to note that it is related in many ways to the philosophical basis of Traditional Chinese Medicine and of many other traditional medical practices (Table 4-1).

| Humor | Associated Element | Energetic Qualities |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Air | Hot, moist |

| Phlegm | Water | Cold, moist |

| Black bile | Earth | Cold, dry |

| Yellow bile | Fire | Hot, dry |

MEANWHILE IN JAPAN

Kampo (also written Kanpo) is based on Traditional Chinese Medicine and literally means “the Han Method,” referring to the herbal system of China that developed during the Han Dynasty. Cultural contact between China and Japan has occurred since ancient times. There is a story about a Chinese Emperor (reign: 221-210 bc) who is said to have sent emissaries by ship on the Eastern Sea to find the herb of immortality; it is suggested that they returned from Japan at the end of their mission with ganoderma (lingzhi; Japanese: reishi). Some Chinese medical works were introduced to Japan as early as the 4th or 5th Century ad, coming first by way of Korea, which had adopted Chinese medicine by that time. Historical records indicate that a Korean physician named Te Lai came to Japan in 459 ad, and that a Chinese Buddhist named Zhi Cong brought medical texts with him to Japan via Korea in 562 ad. It was during this period that the Chinese written language was adopted in Japan, which enabled people to learn from China about Buddhism, Confucianism, governmental organization, and the divination arts and opened the way for study of Chinese medicine. Kampo encompasses acupuncture and other components of Traditional Chinese Medicine but relies primarily on prescription of herb formulas. It differs today from the practice of Chinese herbal medicine in mainland China primarily in its reliance on a different basic collection of important herb formulas and a somewhat different group of primary herbs. Kampo medicine is widely practiced in Japan today (Dharmananda, 2004).

THE RISE OF ROME

He also recommended for bloat in cattle a drench of wild myrtle and wine mixed with hot water. For ulceration of the lungs, he recommended administration of cabbage leaves baked in oil. He also recommended a seton (a foreign body, more recently of cloth, introduced into tissue to elicit drainage or form an open tract for drainage of a wound) of white hellebore through the ear and a daily mixture of leek juice, olive oil, and wine to “avert death of cattle” (Smithcors, 1957).

Dioscorides classified plant medicines according to the state of the plants themselves (with seasonal variations) and their effects on people—this was a drug affinity system (Riddle, 1985) that had little to do with mystical powers or cosmic relationships that would later characterize the alchemical herbology of Culpepper. It became the foremost classical source of modern botanical terminology and the leading pharmacologic text for the next 1600 years. An illuminated copy prepared in the year 512 is now housed in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

The second Greek physician who had a lasting impact was Claudios Galenos (131-201 ad), who is generally referred to as Galen. He learned much about anatomy through his work treating professional gladiators. He developed an interest in anatomy and skills as a surgeon, and he dissected pigs, goats, and apes and applied what he found to the human body. He was strongly influenced by Hippocrates’ Four Humors and his theory was built on Hippocrates’ idea that the body was made up of four liquids—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—and that imbalances in one of these humors might be treated with a substance that opposed that tendency. For instance, psoriasis is considered a hot and dry condition, so Galen would suggest that the patient drink cool liquids, eat cold foods, and use a cool, wet herb such as plantain. He wrote more than 500 books on medicine and developed a system of pharmacology and therapeutics. Galen’s humoral theory and Alexandrian Greek medicine shaped Islamic and European medicine for the next 1400 years. His books were used at medical schools until the Renaissance.

Other early Roman writers of note on the topic of veterinary medicine include Vegetius, author of Mulomedicina, a comprehensive equine veterinary text compiled from works of the previous authors Pelagonius, Chiron, and Apsyrtus (Mezzabotta, 1998).

THE DARK AGES

The writings of the Dark Ages in Europe are largely lost to us, but some books from those times remain. Anglo-Saxon herbals were published from the 7th to the 11th centuries (Table 4-2). The medicine of this age incorporated many charms, in addition to the plants; Christian prayers probably replaced older pagan charms over time. The herbs that appeared most commonly included betony, vervain, peony, yarrow, mugwort, and waybroad (plantain). There are four known texts from the 10th century; these are now held by the British Museum and include Leech Book of Bald, Lacnunga, Herbarium of Apuleius (a translation from the 5th century), and a translation from Petronius’ Practica Petrocelli Salernitani entitled περι´ Διδαξε´ως (which means “about learning/instruction”).

TABLE 4-2 Examples of Anglo-Saxon Veterinary Medicine

| Diagnosis | Treatment | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Sick cattle | “Take the wort, put it upon gledes and fennel and hassuck and “cotton” and incense. Burn all together on the side on which the wind is. Make it reek upon the cattle. Make five crosses of hassuck grass, et them on four sides of the cattle and one in the middle. Sing about the cattle the Benedicite and some litanies and the Pater Noster. Sprinkle holy water upon them, burn upon them incense and give the tenth penny in the Church for God, after that leave them to amend; do this thrice.” | Lacnunga |

| To prevent sudden death in swine | “Sing over them four masses, drive the swine to the fold, hang the worts upon the four sides and upon the door, also burn them, adding incense and make the reek stream over the swine.” or “Take the worts of lupin, bishopwort, hassuck grass, tufty thorn, vipers bugloss, drive the swine to the fold, hang the worts upon the four sides and upon the door.” | Lacnunga |

| Elf-shot horse | “If a horse be elf-shot, then take the knife of which the haft is the horn of a fallow ox and on which are three brass nails, then write upon the horse’s forehead Christ’s mark and on each of the limbs which thou mayest feel at; then take the left ear, prick a hole in it in silence, then strike the horse on the back, then it will be healed. And write upon the handle of the knife these words—‘Benedicite omnia opera Domini dominum.’ Be the elf what it may, this is mighty for him to amend.” or “If a horse or other neat be elf-shot take sorrel-seed or Scotch wax, let a man sing twelve Masses over it and put holy water on the horse or on whatsoever neat it be; have the worts always with thee. For the same take the eye of a broken needle, give the horse a prick with it, no harm shall come.” | Leech Book of Bald |

| “If a beast drinks an insect” | Sing this: “Gonomil, orgomil, marbumil, marbsai, tofeth.” | Leech Book of Bald |

| Drowned bees | Place them in warm ashes of pennyroyal and then, “they shall recover their lyfe after a little tyme as by ye space dissertation.” | The Boke of Secretes of Albartus Magnus of the Virtues of Herbes, Stones, and Certaine Beastes |

One of the most interesting Middle European monastic personalities was German abbess Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179). Remnants of Greek medicine were evident in her writings, which retained some of the old herb characteristics but introduced a new spiritualism that reflected her love of God and her Old Testament belief that everything in creation was made to serve man (Hozeski, 2001):

Hildegard wrote Causeae et Curae and Physica, in which she described causes of diseases and their cures. She compiled the beginnings of a Germanic herbal knowledge and wrote widely on devotion, mysticism, and healing. She used the four-element and four-humor system, and her approach integrated body, mind, and spirit with specific prescriptions for herbs, diet, and gems. She also wrote Liber Simplicis Medicinae, in which she prescribed different herbs for cattle, goats, horses, pigs, and sheep (Haas, 2000). Currently, the writings of Hildegard are undergoing a revival in the German-speaking world.

Cold in the Third Degree

Purslane, Houseleek, Everlasting, Orpine, etc. Seeds of Henbane, Hemlock, Poppy.

Dry in the First Degree

Agrimony, Chamomile, Eyebright, Selfheal, Fennel, Myrtle, Melilot, Chestnuts, Beans, Barley, etc.

ARABIC MEDICINE

In the 12th century, Ibn al-Wwam wrote “Kitab Al-Falaha,” a treatise on agriculture with a section on veterinary medicine. The 33rd chapter discusses diseases of the horse. Redness in the eye was said to be cured with rose water, blepharitis and conjunctivitis with centaury or saffron, mange in the ears or on the nose with saffron and sulphur, stomatitis with powder of pomegranate shells, headache with a linseed cataplasm, leeches in the mouth, nose, or throat with olive oil, and red urine with white pepper (Erk, 1960).