4 Neonatal Nutrition

Case 4-1 Normal Foal Nutritional Needs

The foaling was attended, and no complications were observed. At the time of her examination, ’03 Honeysuckle was standing, active, and had a bright attitude (Figure 4-1). The owner observed the foal initiated suckling when she was approximately 1½ hours old, and since then, she nursed several times per hour. The owner also observed her pass feces within the last hour and urinate at least once since birth.

NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS OF THE NORMAL FOAL

The National Research Council’s Nutrient Requirements of Horses does not provide specific advice on feeding foals less than three months of age, and information for this age group is sparse.1 Some indication of a young foal’s requirements has been derived by observation of the normal feeding behavior, determination of milk consumption, and evaluation of milk composition.

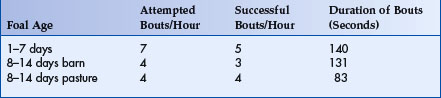

The high metabolic needs of the foal are met through frequent feedings. Carson and Wood-Gush reported observations of stabled and pastured mares and foals, and measured the number of successful nursing bouts demonstrated by foals at various ages.2 They defined a nursing “bout” as “a period of nursing activity delimited by intervals of non-nursing activity lasting for 27 seconds or longer.” Within nursing bouts, activity was divided into suckling, nosing, and interval behavior, which indicated periods of less than 27 seconds when foals were neither suckling nor nosing. Their findings regarding foal nursing behavior are summarized in Table 4-1.

This study also indicated that normal foals successfully suckled each teat an equal number of times. Observations of mare-foal interaction indicated that during the first week of the foal’s life the mares assisted the foals in finding the teat by shifting to positions that increased accessibly. For the following one to two weeks, the mares demonstrated more resistant behavior resulting in early termination of foal nursing. After this period, the mares became more cooperative until approximately 16 weeks postpartum. From 16 to 24 weeks, termination of the nursing sessions again became increasingly frequent.2

Light-breed mares produce approximately 3% of their body weight in milk/day for the first 3 months of lactations (12 to 13 liters for a 450-kg mare).3 Using a double isotope dilution or radio-labeled water (3H2O) technique, studies have shown that 11-day-old foals consume as much as 27% of their body weight in the form of milk (12 liters for a 45-kg foal).3,4 Mare’s milk contains a caloric value of approximately 480-600 kcal/l. This amount of milk provides a mean of 159 kcal/kg/day gross energy and 7.2 g crude protein/kg/day.4 The volume decreases to 19.3% (98 kcal/kg/day gross energy and 3.7 grams crude protein/kg/day) by the time the foal reaches 39 days of age.3 This information demonstrates the significant energy requirements of the growing foal, and the rapid rate at which nutritional requirements change over the foal’s first six weeks of life.

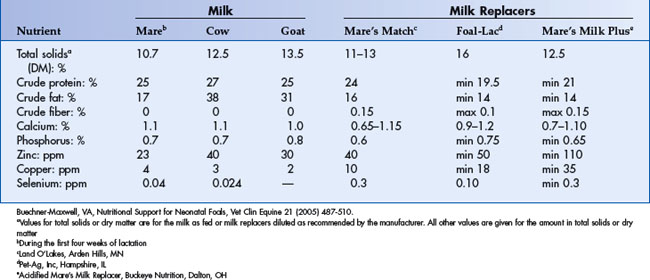

Detailed information regarding the composition of mare’s milk has been reported elsewhere.3,4 Equine milk is low in energy and high in water content as compared to cow’s and goat’s milk, and contains less fat, protein, and total solids, and more lactose.5 The composition of mare’s milk also changes over time. Initially, there is a decrease in milk total solids and protein composition from days 11 to 25.3,6–14 Some studies also report a decline in fat content during this period, although this has not been a consistent finding.3,6,7,10–12 The change in milk during the first three weeks postpartum is attributed a gradual change from colostrum to mature milk. Once mares reach mid-lactation (day 20 to 65 postpartum), milk composition is less changeable.3 A comparison of published results suggests that, as fed, total solids (10.4% to 11.2%) and sugar content (6.0% to 6.9%) of milk do not change significantly between 21 and 60 days after birth.15 Crude protein content declines minimally, and crude fat content does not follow a trend.3 A significant animal effect (variation from animal to animal) in all contents of milk is also observed, with the exception of crude protein (whole-milk basis) and sugar (dry-matter basis).3 These findings complicate efforts to describe the nutritional needs of the neonatal foal based upon the diet that they normally consume, since the diets of the normal foal change rapidly throughout preweaning life and vary significantly from individual to individual.

Management of neonatal nutrition begins before birth. Feeding management of the broodmare has been described elsewhere, and major points will be briefly highlighted here.1,16–19 The mare’s nutritional needs increase during the last three months of pregnancy and continue to increase during the first three months of lactation.1 While supplementing adequately fed mares does not significantly improve foal growth, restricting mare’s feed during lactation compromises foal growth.20

Indirect evidence from epidemiological and animal studies indicates that failure to meet nutritional requirements for the pregnant woman results in prenatal growth retardation and an increased risk of the child developing coronary heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes later in life.21–24 This outcome is due to interruptions in the immediate growth pattern of tissue, resulting in a long-term effect on somatic cell programming, growth, and development.

The nutrient composition of milk may also be affected by the mare’s diet. Mares fed a calcium-deficient diet before parturition and during lactation produced foals that were born with thinner and mechanically weaker bones as compared to foals from mares fed an adequate diet. This difference persisted for 40 weeks after parturition.25 In contrast, neonatal goiter has been associated with excessive supplementation of pregnant mares with dietary iodine.26,27 These examples support the need to pay close attention to the broodmare’s diet during pregnancy and lactation to ensure the foal is receiving optimal nutrition in utero as well as after birth.

GASTROINTESTINAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE FOAL

At birth, lactase is the primary disaccharidase in the equine small intestine. This makes sense as the primary energy source in mare’s milk will be lactose. As the foal matures, maltase activity increases until it is equal to the lactose activity at three to four months of age. Maltase is the predominant disaccharidase in the mature small intestine.28 Also, during the first few months of life there is a significant increase in length and diameter of the foal’s small intestine. By five to six months of age, the foal begins to mimic the adult feeding pattern of grazing, and it will begin to develop the large colon and cecum.29

COPROPHAGY

Coprophagy by foals is considered normal behavior and does not indicate inadequate nutrient availability (Figure 4-2). This behavior was initially described in the literature in 1954.30

Fig. 4-2 Coprophagy is normal in young foals and is not considered an indicator of inadequate nutrition.

More recent studies indicate that foals engage in coprophagy as early as the first week of life, and that this behavior is most frequently observed during the first two months.31 The most common source of the feces is the mare, although feces from other adult horses may also be consumed.

While it is not known why foals participate in this behavior, several theories have been proposed. Crowell-Davis and Houpt predicted that pheromones in the feces signaled consumption by the foal, while Francis-Smith and Wood-Gush suggested that coprophagy provided gut flora and vitamins to the foal.31,32 Foals are reported to be deficient in deoxycholic acid, and these researchers further hypothesized that the mare’s feces served as a source of this nutrient. Deoxycholic acid contributes to gut immunocompetence and myelination of the nervous system, and may protect foals from developing gastrointestinal diseases like necrotizing enterocolitis. Consequently, coprophagy should not be discouraged in the neonatal foal.

ADEQUACY OF THE FOAL’S DIET

Foals that receive adequate nutrition typically display distinct periods of nursing and rest. Based upon the results previously discussed, one-week-old foals should latch on and suckle for about 1½ minutes, five to seven times per hour. Foals that are not receiving adequate nutrition may attempt to suckle more frequently, and will often display agitation in between attempts. Foals may also be more aggressive toward the mare, with frequent bouts of bunting the udder, stamping, and tail flagging. The mare may respond by interrupting the foal’s attempts to suckle and maneuvering in such a way to keep the foal away from the udder. These signs alone do not support inadequate nutrition, but signal the need for further investigation.

Normal foals are reported to produce 148 ml/kg/day of urine, which is approximately 10 times that of the adult horse on a per-body weight basis.33,34 As a result, foals urinate nearly every hour. Less-frequent urination may be an indication that milk intake is restricted, especially if the foal does not have free choice access to water.

Foals begin to pass meconium within six hours of birth, and complete passage by 24 hours. Meconium evacuation is stimulated by ingestion of colostrum.35 After meconium is passed, defecation occurs several times per day. Normal foal feces is tan in color, formed, and somewhat pasty. Although there are many reasons for foals to decrease their fecal production and/or demonstrate a change in fecal consistency, inadequate milk ingestion should be considered as a possible cause.

At birth, foals should be about 11% of their mature body weight.36 Young, healthy foals experience rapid weight gain and growth when receiving appropriate nutrition. Neonatal foals are reported to gain 1.3 to 1.5 kg/day during the first 30 days of life.4,37 Thoroughbred foals attain about 83% of their total body height and approximately 46% of their body weight by six months of age, doubling their weight in the first month. Restricting mare’s feed during lactation diminishes milk production and compromises foals growth.20 To detect subclinical malnutrition, the foal’s height and weight should be measured every week and compared to published normal growth charts for foals of similar size and breed.15

BODY CONDITION SCORING

Methods for evaluating the foal’s body condition have been reported. Evaluation on a weekly basis permits identification of foals that may be receiving less than adequate nutrition.38 Foals are rarely born fat, so one can use the lower 1-5 body scores of the 1-9 Henneke Body Condition Scoring System39 (Table 4-2, Figures 4-3, 4-4, and 4-5). Reasons for poor body condition in a foal can be divided into prepartum and postpartum causes (Table 4-3). Prepartum causes include prematurity, placental insufficiency (IRGR), twinning, and poor maternal body condition. Postpartum causes may include catabolism from a systemic illness, malabsorption/maldigestion secondary to lactase deficiency or diarrhea, agalactia in the mare, compromised ability to suckle or chew, and foal rejection.

Table 4-2 Assigning a Body Condition Score to a Young Foal39

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Extremely emaciated: spinous processes, ribs, tuber coxae, tailhead, and tuber ischii very prominent; shoulder and neck structures evident (Figure 4-3) |

| 2 | Emaciated: Slight fat covering the base of the spinous processes; slightly rounded feel to traverse processes and ribs; shoulder and neck structures barely noticeable |

| 3 | Thin: Fat buildup midway down traverse processes; slight fat over ribs; individual vertebrae not discernible (Figure 4-4) |

| 4 | Moderately thin: Slight ridge along back; faint outline to ribs; fat can be felt over tailhead and withers; shoulder and neck structures not thin |

| 5 | Moderate or normal: Back flat; ribs not visible but easily palpated; fat around tailhead feels spongy, withers rounded over the spinous process; shoulder and neck structures blend well into body (Figure 4-5) |

Table 4-3 Reasons for Poor Body Score in Foals

| Prepartum Causes | Postpartum Causes |

|---|---|

| Prematurity | Agalactia in the mare |

| Twinning | Foal rejection by the mare |

| Placental insufficiency (IUGR) | Anorexia secondary to disease |

| Malabsorption/maldigestion | |

| Compromised ability to suckle or chew |

1 National Research Council. Nutrient requirements of horses, ed 5. Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences, 1989.

2 Carson K, Wood-Gush DG. Behaviour of thoroughbred foals during nursing. Equine Vet J. 1983;15:257.

3 Oftedal OT, Hintz HF, Schryver HF. Lactation in the horse: Milk composition and intake by foals. J Nutr. 1983;113:2096.

4 Martin RG, McMeniman NP, Dowsett KF. Milk and water intakes of foals sucking grazing mares. Equine Vet J. 1992;24:295.

5 Koterba AM. Chapter 34: Nutritional support: Enteral feeding. In: Koterba AM, Drummond WH, Kosch PC, editors. Equine Clinical Neonatology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990.

6 Linton R. The composition of mare’s milk. J Agric Sci. 1931;21:669.

7 Linton R. The composition of mare’s milk II. J Dairy Res. 1937;8:143.

8 Holmes A, McKey B, Wertz A, et al. The vitamin content of mare’s milk. J Dairy Sci. 1946;29:163.

9 Holmes A, Spelman A, Smith C, et al. Composition of mare’s milk as compared with that of other species. J Dairy Sci. 1947;30:385.

10 Flade E. Milchleistung und Milchqualitat bei Stuten. Arch Tierz. 1955;9:381.

11 Ullrey DE, Struthers RD, Hendricks DG, et al. Composition of mare’s milk. J Anim Sci. 1966;25:217.

12 Johnston RH, Kamstra LD, Kohler PH. Mares’ milk composition as related to “foal heat” scours. J Anim Sci. 1970;31:549.

13 Balbierz H, Nikolajczuk M, Poliwoda A, et al. Studies on colostrum whey and milk proteins in mares during suckling period. Pol Arch Weter. 1975;18:455.

14 Bouwman H, van der Schee W. Composition and production of milk from Dutch warmblood saddle horse mares. Z Tierphysiol Tierernaehr Futtermittelkd. 1978;40:39.

15 Lewis LD. Growing horse feeding and care. Media, PA: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

16 Donoghue S, Meacham TN, Kronfeld DS. A conceptual approach to optimal nutrition of brood mares. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 1990;6:373.

17 Pugh D, Williams W. Feeding foals from birth to weaning. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 1992;14:526.

18 Pugh DG, Schumacher J. Feeding and nutrition of brood mares. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 1993;15:106.

19 Lewis LD. Broodmare feeding and care. Media, PA: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

20 Banach MA, Evans JW, Blacksburg, VA, 1981, Virginia Polytechnic Institute.

21 Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1995;311:171.

22 Osmond C, Barker DJ. Fetal, infant, and childhood growth are predictors of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension in adult men and women. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):545.

23 Schwarzenberg SJ, Kovacs A. Metabolic effects of infection and postnatal steroids. Clin Perinatol. 2002;29:295.

24 Dusick AM, Poindexter BB, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Growth failure in the preterm infant: Can we catch up? Semin Perinatol. 2003;27:302.

25 Glade MJ. Effects of gestation, lactation, and maternal calcium intake on mechanical strength of equine bone. J Am Coll Nutr. 1993;12:372.

26 Drew B, Barber WP, Williams DG. The effect of excess dietary iodine on pregnant mares and foals. Vet Rec. 1975;97:93.

27 Eroksuz H, Eroksuz Y, Ozer H, et al. Equine goiter associated with excess dietary iodine. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2004;46:147.

28 Roberts MC. The development and distribution of mucosal enzymes in the small intestine of the fetus and young foals. J Reprod Fertil. 1975;23(Suppl):717-723.

29 Smyth GB. Effects of age, sex, and post mortem interval on intestinal lengths of horses during development. Equine Vet J. 1988;20:104-108.

30 Taylor EL. Grazing behavior and helmenthic disease. Br J Anim Behav. 1954;2:61.

31 Crowell-Davis SL, Houpt KA. Coprophagy by foals: Effect of age and possible functions. Equine Vet J. 1985;17:17.

32 Francis-Smith K, Wood-Gush DG. Coprophagia as seen in thoroughbred foals. Equine Vet J. 1977;9:155.

33 Brewer BD, Clement SF, Lotz WS, et al. A comparison of inulin, para-aminohippuric acid, and endogenous creatinine clearances as measures of renal function in neonatal foals. J Vet Intern Med. 1990;4:301.

34 Brewer BD, Clement SF, Lotz WS, et al. Renal clearance, urinary excretion of endogenous substances, and urinary diagnostic indices in healthy neonatal foals. J Vet Intern Med. 1991;5:28.

35 Koterba AM. Chapter 6: Physical Examination. In: Koterba AM, editor. Equine clinical neonatology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990.

36 Wilson JH. Feeding considerations for neonatal foals. Proc 24th Annu Conv AAEP. 1987;33:823.

37 Hintz HF. Growth rate of horses. Proc 24th Annu Conv AAEP. 455, 1978.

38 Paradis MR. Nutrition and indirect calorimetry in neonatal foals. Proc. 19th ACVIM Denver, CO. 2001;19:245.

39 Henneke DR. A condition score pyslen for horses. Equine Pract. 1985;7:13-15.

Case 4-2 Orphan Foal

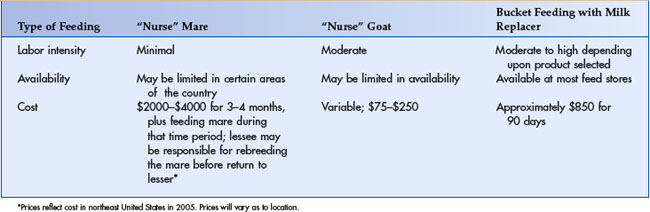

’03 Lonely Heart is a Quarter Horse filly that appears to be in good health (Figure 4-6). She has a body condition score of 5 on the Heneke system (1-9). She appears hungry and is attempting to suckle on any part of your body that she can. You discuss options of providing nutrition to this healthy foal with Mrs. Smith. These include the lease of a “nurse” mare; the use of another species, such as a goat, to rear the foal; and the use of mare’s milk replacers. You put forth the pros and cons associated with each choice (Table 4-4).

NURSE MARES

Nurse mare chutes have been designed and are described elsewhere.1 These chutes provide the advantage of permitting the foal to nurse with minimal restraint of the mare. Feeding the mare while the foal is nursing is also recommended. Mares accept foals by becoming familiar with their associated smell, sights, and sounds.2 Most mares accept foals within 12 hours to 3 days, although rarely it may take as long as 10 days.1

Besides providing the most natural nutrition, nurse mares also provide psychological support for the foal. Foals learn how to behave like horses from their dams.

NURSE GOAT

Nurse goats have also been used to assist in raising orphan foals. Larger-breed dairy goats (such as Nubians) provide the best candidates for this purpose. Goats may be taught to stand on hay bales to provide better udder access to the foal.3,4 However, even large foals can learn to position themselves to facilitate suckling. Orphan foals that are grafted on to goats should be introduced to creep feed (with milk pellets or grain mix, as described later) by two weeks of age or earlier, and should be provided access to free-choice water and hay. Alternatively, more than one goat may be provided to meet the foal’s nutritional requirements.3 Goat’s milk is not a perfect match for mare’s milk; it is higher in most nutrients such as fat, protein, and lactose and lower in water content. Poor weight gain and metabolic acidosis have been reported in neonatal foals that were fed 135 kcal/kg/day of goat’s milk.5 The goat’s weight and the foal’s growth (weight and height) should monitored closely to prevent development of poor body condition in either animal.

MILK REPLACERS

When a maternal substitute is unavailable, foals may be hand-reared. A number of commercial mare’s milk replacers are available (Table 4-5). When selecting a milk replacer, it is important to obtain a product analysis sheet from the manufacturer. The milk replacer should closely match mare’s milk in energy density (0.5 kcal/kg as feed), crude protein (22% dry matter), crude fat (15% dry matter), crude fiber (less than 0.2% dry matter), and total solids (11% as feed).6,7 Replacers should also match the mineral and vitamin content of mare’s milk as described by the National Research Council’s Nutrient Requirements of Horses.8

The carbohydrate source in the replacer milk should be checked. Some products use maltodextrins and corn syrup in addition to lactose. Because maltase levels are not high in the first month of life in the foal, these forms of carbohydrate may be undigestible. Undigested sugars may result in fermentation in the colon, increasing gas production and osmotic diarrhea.9

In a comparison of element concentrations in mare’s milk versus commercial mare’s milk replacement products by Rook and colleagues, most milk-replacement products meet or exceed the concentrations of calcium, iron, sulfur, potassium, sodium, copper, phosphorus, zinc, and magnesium.10 The differences in these elements between the milk substitutes and mare’s milk were not thought to be a problem except in a few medical conditions. In particular, high levels of potassium may be a problem in foals with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis or renal compromise. A scientific evaluation of the relationship between replacer formulation and foal performance has not been reported. Consequently, the effect of variations in milk replacer formula on the general health of the foal is not known.10

FEEDING METHODS AND SCHEDULE

Foals that have been nursing a mare or suckling from a bottle will need to be trained to drink from a bucket. To train a foal, allow it to become hungry by waiting to feed it for several hours. Place a damp finger in the foal’s mouth and gently rub it between the tongue and the palate to stimulate a suckle response. Once the foal is suckling, gently guide its muzzle down to the milk. This process may need to be repeated multiple times to educate the foal to drink from the bucket. Teaching foals to drink from a bucket requires patience, and excessive force should not be used to position the foal’s muzzle in the milk (Figure 4-8).

Turner reported that foals in their study took 10 to 120 minutes to learn how to bucket feed.11 To facilitate the young foal’s ability to identify the feed, light-colored buckets, preferably yellow (personal communication with Dr. Sarah Stoneham) should be used for the milk. Milk does not need to be warmed before feeding, and can be provided at room temperature.12

The healthy foal will consume 25% to 30% of its body weight in kilograms in mare’s milk. The foal should be offered similar volumes of milk replacer if the product contains a caloric density (0.48 kcal digestible energy/ml) and nutritional composition (see Table 4-5) that closely mimics mare’s milk. The amount of liters of milk that a foal ingests on a daily basis can be estimated by multiplying its body weight in kilograms by 0.25 to 0.30 to arrive at the number of liters/day that the foal needs to eat. This number is then divided by the number of feedings per day to arrive at the amount of milk needed per feeding.

Most manufactured products (excluding acidified milk replacer) must be made fresh and fed frequently. The most convenient product for hand raising foals is acidified milk replacer (Buckeye Nutrition, Dalton, Ohio) and is especially useful when raising more than one orphan at a time. Acidified milk remains fresh for up to three days, but the manufacturer recommends discarding old milk, cleaning the feeding bucket, and providing fresh milk at least twice a day. This practice ensures that the milk and bucket remain sanitary, and allows the caretaker to access the foal’s appetite on a regular basis.

Change in fecal consistency may occur when foals are fed milk replacers. If the product contains sugars other than lactose, the foal may develop diarrhea.13 In addition, some milk replacers are more concentrated than mare’s milk when mixed as per the manufacturer’s recommendations, resulting in an increase in the percentage of total solids in the diet. The volume of water with which the replacer is reconstituted should be adjusted so that the final concentration of total solids is approximately 11% (similar to mare’s milk). Making this adjustment will often resolve changes in fecal consistency associated with feeding milk replacer, but foals that experience these problems should be carefully monitored until their manure returns to a normal consistency and volume.

CREEP FEEDING

Creep feeding is the supplementation of a foal’s diet with milk pellets and/or grain mix while they are receiving milk or milk replacer. Foals that are coupled with normal mares begin sampling the mare’s feed as early as 10 days, but do not require creep feed until they approach four weeks of age because the amount of milk made by a normal mare is adequate to meet the foal’s requirements for the first month of life.4,12 In contrast, if the mare’s milk production is inadequate or the foal is coupled with a single nurse goat, then creep feeding should be encouraged starting several days after birth.

Foals consuming milk replacer or requiring early weaning for other reasons should also be introduced to creep feed shortly after birth. Milk pellets are the feed of choice when introducing young foals (two to three days old) to creep feed. To stimulate the foal’s interest in these pellets, a few should be placed in its mouth several times a day until the foal begins to eat unassisted. To facilitate the foal’s acceptance, pellets should also be made available for free-choice consumption. Regardless of the amount the foal eats, the feeder should be emptied twice a day of any residual feed, cleaned, and refilled with fresh milk pellets. Once the foal is consuming 2 to 3 pounds of milk pellets per day, a good quality grain mix can be introduced.12

If the foal is not already familiar with eating creep feeds, grain mix must be introduced to the foal by placing small quantities in the foal’s mouth several times per day. Grain mixes for pre-weaning foals should contain 16% crude protein, 0.9% calcium, and 0.6% phosphorus. Feeds for preweaning foals should also contain 60 ppm zinc, 50 ppm copper, 1365 IU/lb vitamin A, and 45 IU/lb vitamin E.12 If the foal is already consuming milk pellets, small portions of the grain mix should be mixed with the pellets initially. Over four to six weeks, the proportion of milk pellets should be reduced while the quantity of grain mix is increased, until the pellets can be eliminated from the diet.

High-quality hay should also be made available for the foal. However, foals that consume large quantities of legume hay may develop diarrhea. This hay alone is not recommended, because the high protein and calcium content may contribute to problems such as developmental bone disease. Problems associated with feeding high-quality alfalfa hay alone can usually be avoided by mixing the alfalfa with high-quality grass hay. By eight weeks of age, the average foal should be consuming 4 to 6 lbs (1.8-2.7 kg) of creep feed per day, and can be gradually weaned off the milk replacer.12