CHAPTER 3 Ethnoveterinary Medicine: Potential Solutions for Large-Scale Problems?

WHAT IS EVM?

Also sometimes called veterinary anthropology (McCorkle, 1989),† ethnoveterinary medicine or EVM can be broadly defined in this way:

The holistic, interdisciplinary study of local knowledge and its associated skills, practices, beliefs, practitioners, and social structures pertaining to the healthcare and healthful husbandry of food, work, and other income-producing animals, always with an eye to practical development applications within livestock production and livelihood systems and with the ultimate goal of increasing human well-being via increased benefits from stockraising (McCorkle, 1998a).

These aspects in turn embrace local Materia medica, which include minerals and animal products or parts, as well as plants and human-made and natural materials; modes of preparation and administration of ethnoveterinary medicaments; basic surgery; various types of immunization; hydro, physical, mechanical, and environmental treatments and controls; herding, feeding, sheltering, and watering strategies; handling techniques; shoeing, shearing, marking, and numerous other husbandry chores such as ethnodentistry; management of genetics and reproduction; medicoreligious acts; slaughter, as one medical option; and all the various socio-organizational structures and professions that discover, devise, transmit, and implement this knowledge and expertise. These human elements span not only traditional healers of animals (Mathias, 2003) but also families, clans, castes, tribes, communities, cooperatives, dairy associations, other kinds of grassroots development organizations, and more.

Impelled in large part by livestock development projects around the world, EVM has evolved to embrace other topics, such as zoopharmacognosy (animals’ self-medication) as a possible source of EVM ideas; participatory epidemiology; gendered knowledge, tasks, and skills in EVM (Davis, 1995; Lans, 2004); safety in handling and processing food and other products from animals; product marketing and associated agri-business skills; conservation of biodiversity in terms of natural resources, including animal genetic resources (Köhler-Rollefson, 2004); health- and husbandry-related interactions between domestic and wild animals; ecosystem health (i.e., how animals, humans, and their environment can interact to protect or improve the health of all three); EVM-related primary education curricula in rural areas and in training programs for veterinary professionals and paraprofessionals; and policy, institutional, and economic analyses in most of the foregoing realms.

For fuller discussions of all the previously listed topics and themes in EVM, see related studies in Reference Section (Mathias, 2004; McCorkle, 1995, 1998b; McCorkle, 2001). It is important to mention, however, that by far the most-studied element of EVM is veterinary ethnopharmacopoeia, especially the use of botanicals.

HOW HAS EVM EVOLVED?

On the basis of a review of emerging literature along with firsthand research in 1980 among Quechua stockraisers in the high Andes of South America, EVM was finally codified in 1986 as a legitimate field of scientific R&D (McCorkle, 1986). An annotated bibliography on EVM and related subjects followed soon thereafter (Mathias-Mundy, 1989). Published by a US agricultural university program of indigenous knowledge studies within a series on technology and social change, this item was available only as “grey literature.” Nevertheless, it was in high demand. Only in 1996 did the first formally published anthology of scientific studies dedicated solely to EVM reach print (McCorkle, 1996).

One major stimulus was the World Health Organization’s project to incorporate valid human-ethnomedical techniques and—on the model of barefoot doctors in China—local medical practitioners into real-world strategies for achieving WHO’s goal of “basic healthcare for all.” EVM seeks to do likewise for livestock; e.g., via the creation of cadres of community-based veterinary paraprofessionals (ILD Group 2003) that ideally deliver both conventional and ethno-options. EVM embraces a cost-effective return to the “one medicine” concept, in which such healthcare services are delivered jointly to both animals and humans—especially in poor and/or remote areas (Green, 1998; McCorkle, 1998b; others in the special section on human and animal medicine in this issue of Agriculture and Human Values), along with the creation of cadres of community-based veterinary paraprofessionals (IDL Group, 2003) that, ideally, deliver both conventional and ethnomedical options.

Pioneering international NGOs in EVM included: in the US, Heifer Project International (HPI), notably in Cameroon and the Philippines; the Philippines-based International Institute for Rural Reconstruction (IIRR); and the UK Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG), which worked particularly in East Africa. Later NGO leaders included India’s ANTHRA group, which focuses on livestock development among women in that country; also in India, the Bharatiya Agro Industries Foundation (BAIF); Germany’s League for Pastoral Peoples (LPP), especially with its work on camels; the US Christian Veterinary Mission; and Vétérinaires Sans Frontières (VSF/Switzerland, 1998).

It was also helpful that between 1986 and 1996, new outlets and technologies came into being for more rapid, informal, and globally inclusive exchanges of EVM observations and information across a much wider range of national and disciplinary groups. A pioneering outlet in this regard was the Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor. Based first in the United States and later in the Netherlands, this development magazine was published from 1993 to 2001 and was distributed gratis to developing world subscribers. In 1999, it was followed by a global electronic mailing list devoted solely to EVM. Recently, this list was expanded topically and renamed the Endogenous Livestock Development List (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/ELDev/). Although initiated and funded in the developed world, all these efforts relied on hands-on management by and content input from a panel of editors who represented nearly all continents of the globe.*

A notable example is the first-ever international conference, Ethnoveterinary Medicine: Alternatives for Livestock Development. Held in India in 1997, it was supported by the World Bank and many other donors, plus pharmaceutical companies. This event was hosted by India’s BAIF based on a proposal written by Indian, German, UK, and US scientists. Together they thereafter produced two volumes of formal abstracts and proceedings (Mathias, 1999). The conference boasted 33 formal papers and nearly as many poster papers on EVM. Disciplines represented ran from A (anthropology) to Z (zoology) and included all the animal and veterinary sciences in between, along with traditional veterinary praxis as represented by local healers from India.

At this point, a patent need arose to update, expand, and more tightly focus the 1989 bibliography referenced earlier. This was done, and the bibliography was released through a major publishing house in international development, with financial support provided by the UK Department for International Development. The new bibliography (Martin, 2001) boasted 1240 annotations spanning 118 countries, 160 ethnic groups, and 200 health problems of 25 livestock breeds and species. It covered publications dated through December of 1998.

Since 1998, EVM has rocketed ahead. Publications are increasing exponentially, now with a greater number of developed-world authors researching or writing about EVM in their own cultures and native lands. Recent examples of publications and conferences in this vein come from Canada (TAHCC, 2004), Italy (Guarrera, 1999, 2005; Manganelli, 2001; Pieroni, 2004), the Netherlands (van Asseldonk, 2005), and Scandinavia (Waller, 2001).

This trend is due in part to the fact that established scientific outlets in numerous disciplines—like the Revue Scientifique de l’Office Internationale des Epizooties (OIE, 1994)—are now more open than ever to papers on EVM. Also, new outlets are coming into being. For instance, the Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine plans to mount a series of articles on EVM beginning in 2006. Even more important is the fact that the literature is beginning to demonstrate a salubrious move up from mere description of EVM knowledge and practices to more critico-analytic and applied studies. The two cases presented in this chapter are indicative.

In 1994, 1996, and 1998, the NGOs IIRR, ITDG, and VSF held workshops on EVM in Southeast Asia, Eastern Africa, and Sudan, respectively. Meanwhile, in 1997, LLP convened a workshop on both EVM and conventional practices for camel health and husbandry (Köhler-Rollefson, 2000). In 1999, a conference was held in Italy on “Herbs, Humans and Animals—Ethnobotany & Traditional Ethnoveterinary Practices in Europe” (Pieroni, 2000). In 2000, an international conference on EVM was mounted in Africa and hosted by Nigeria’s Ahmadu Bello University (Gefu, 2000).

Later, a participatory workshop on EVM was held in the Canadian province of British Columbia, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of the government of Canada (see http://bcics.uvic.ca/bcethnovet/rationale.htm). The year 2005 witnessed the first Pan-American conference on EVM in Latin America, which was organized and hosted by a Guatemalan university, with financial support provided by the Guatemalan government. Also in 2005, various Mexican universities, research centers, and government agencies hosted an international conference on animal genetics and the invaluable animal germplasms, including disease-resistant ones that local peoples have developed and husbanded down through time.

WHY THE INTEREST IN EVM?

WHERE IS EVM HEADED NEXT?

Along with others, all the benefits outlined previously have been attested to in the larger literature on EVM. Doubtless, readers will think of others. But beyond providing more culturally comfortable, practical, and economical alternatives or complements to conventional medical approaches, R&D in EVM may conceivably help solve problems left in the wake of, or new to, conventional medicine. An example of the former is ailments that have become resistant to overprescribed or misused commercial drugs like antibiotics and commercial parasiticides. Viral diseases exemplify the latter, in that antigenic shifts may render conventional vaccination responses unrealistic (Atawodi, 2002). Such shifts come about when two varieties of a virus concurrently infect the same host, allowing genomes to recombine into a novel subtype.

Of course, various limitations to EVM have been noted in the literature. Among others are the following claims (after Fielding, 2000).

The first and second concerns above are certainly valid. But the literature suggests that they apply equally to conventional treatments because of import, supply, or price problems with commercial drugs—whether in the developing or the developed world. A case in point involves experiences in modern-day France regarding the relative availability and efficacy of conventional and EVM treatments for sudden outbreaks of sheep disease, some of which are viral (Brisebarre, 1996).

With increased bioprospecting (Clapp, 2002), this trend has intensified and become even more profitable (Lans, 2003). In the developing and the developed world, companies that process or merely package and then retail or wholesale “natural,” “organic,” or “ancient” alternatives based on ethnomedicine for livestock and humans have expanded, proliferated, and specialized. In the past decade alone, a number of companies have sprung up in Europe and on the East and West coasts of the United States to distribute EVM-based herbal preparations, many of which are imported from India. Some of these enterprises even specialize in preparations for a single animal species such as horses (Stephen Ashdown, DVM, personal communication).

EVM AND VIRAL DISEASES: TWO CASES FROM POULTRY PRODUCTION

The cases presented here focus on major viral disease in family poultry enterprises in the developing world. There, more than 80% of poultry are raised in such enterprises. These “backyard birds” provide up to 30% of household protein intake in the form of eggs and meat. Trade in these poultry products and (depending on the culture) in fertilized eggs, chicks, and live birds also contributes significantly to household nutrition and income. Often, this income is used to step up the family farming enterprise through the purchase of larger stock, like pigs, sheep, goats, or even cattle and buffalo (Ibrahim, 1996).

Developed-world producers can ward against such threats with modern immunizations, albeit with the drawbacks already noted. However, many family poultry enterprises in the developing world simply cannot afford commercial vaccines–—even where these are available and reliable (i.e., unexpired, unadulterated, or unfalsified), with trained personnel to administer them (such as community-based paraprofessionals). Although some ethnoveterinary vaccines of variable efficacy do exist for viral diseases of poultry,* poor or remote people in the developing world rely primarily on plant-based prophylactic measures to stave off such ills in their birds.

The question is: Do any such measures really make any difference? To begin to answer this, Cases 1 and 2 below respectively address: Africans’ phytomedical treatments for ills identified as ND; and Africans’ and other peoples’ botanicals for responding to unspecified respiratory signs in poultry, which are here taken as suggestive of AI. Unless otherwise indicated, for Case 1, production data on ND in Africa are drawn from Guèye 1997, 1999, and 2002. For both cases, technical background on the etiological agents and clinical signs of both ND and AI is based mainly on Alexander 2000 and 2004 plus Tollis 2002. Both OIE and WHO offer a periodically updated technical and other information on AI at their websites (www.oie.int. and http.www/who.org).

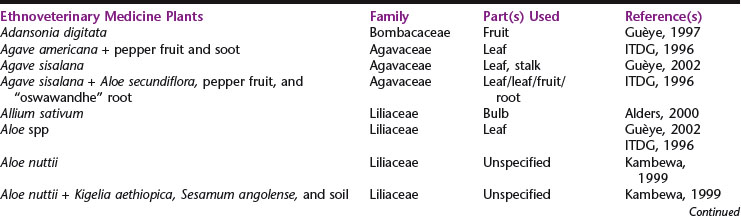

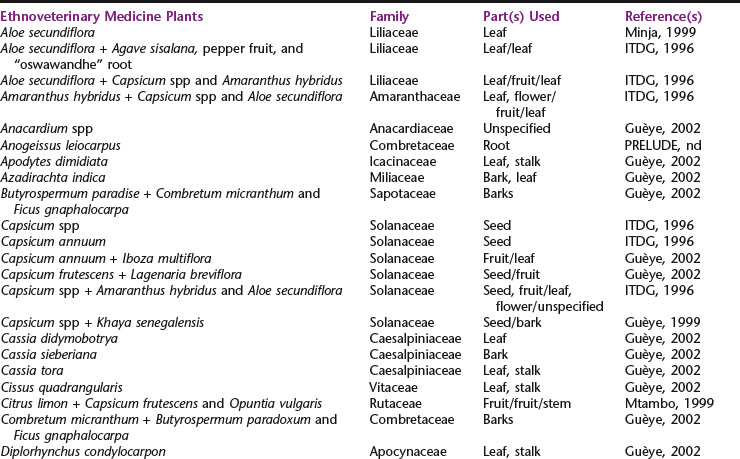

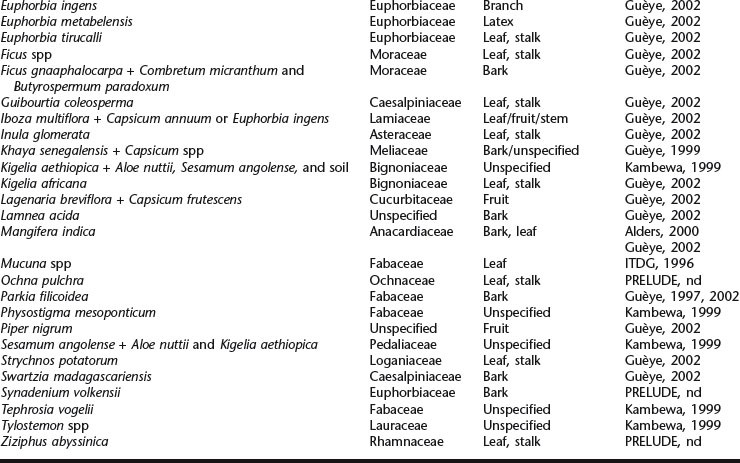

Table 3-1 lists a sampling of the plants involved in such preparations, labeled by the names given in the original scientific paper about them. As discussed in the following paragraphs, a number of these plants have proved promising for combating ND.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree