Section 3 Clinical Signs

Abdominal enlargement with ascites,

Abdominal enlargement without ascites,

Blood in urine: hematuria, hemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria,

Constipation (obstipation), (see also Straining to Defecate),

Coughing blood: hemoptysis, (see also Difficulty Breathing)

Decreased urine production: oliguria and anuria,

Difficulty breathing or respiratory distress: cyanosis, (see also Dyspnea)

Difficulty breathing or respiratory distress: dyspnea,

Difficulty swallowing: dysphagia,

Hemorrhage, see Spontaneous Bleeding,

Increased urination and water consumption: polyuria and polydipsia,

Itching or scratching: pruritus, (see also Hair Loss)

Lymph node enlargement: lymphadenomegaly,

Painful urination: dysuria, see Straining to Urinate

Painful defecation: dyschezia, see Straining to Defecate

Rectal and anal pain, see Straining to Defecate

Regurgitation, (see also Difficulty Swallowing and Vomiting)

Seizures (convulsions or epilepsy),

Spontaneous bleeding: hemorrhage,

Straining to defecate: dyschezia,

Straining to urinate: dysuria,

Swelling of the limbs: peripheral edema,

Uncontrolled urination: urinary incontinence,

Vomiting, (see also Regurgitation)

Vomiting blood: hematemesis, (see also Vomiting)

Weight loss: emaciation, cachexia,

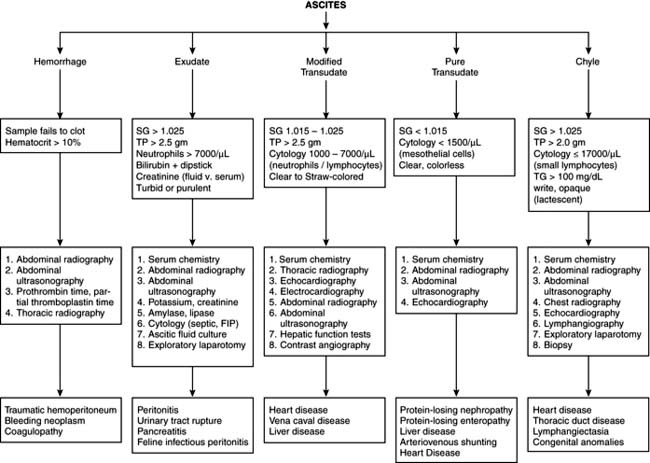

Abdominal enlargement with ascites

Differential diagnosis (Figure 3-1)

Diagnostic plans

1. Physical examination, to establish or rule out cardiopulmonary disease. Evaluate skin and hair coat for signs supporting endocrine disease (especially hyperadrenocorticism).

2. Verify ascites or abdominal enlargement by ballottement, abdominal radiography, abdominal ultrasound, or abdominocentesis.

3. If fluid is present, abdominocentesis, fluid analysis, and, if available, abdominal ultrasound. A laboratory database also is recommended.

Abdominal enlargement without ascites

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic plans

1. History. Establish duration and progression of abdominal enlargement; in females, establish whether or not pregnancy is possible.

2. Abdominal palpation. Note: Preferably accomplished with the patient in right lateral recumbency. Examination is carried out using two hands simultaneously.

3. Abdominal ballottement. Manipulate the abdominal wall in an attempt to determine whether or not an accumulation of fluid exists within the abdomen.

4. Imaging. Abdominal radiograph or abdominal ultrasound.

5. Laboratory profile. Generally conducted to assess patient overall health status.

6. Fine needle aspiration and cytology. Aspiration of solid organs or masses may be indicated.

7. Exploratory surgery. Laparoscopy may be a necessary alternative.

Aggression

Differential diagnosis

Aggressive Behavior in the Dog: Differential Diagnosis According To Origin

From Young MS: Aggressive behavior. In Ford RB, editor: Clinical signs and diagnosis in small animal practice, New York, 1988, Churchill Livingstone.

* These behavior patterns are not pathologic states. They are typical patterns of the species and are therefore normal. Familiarity with the normal, species-typical aggressive pattern of the dog enables differentiation of species-typical patterns from pathophysiologically based aggression. As with many animal behavior problems, species typicality does not lessen the problem’s disruptiveness or danger.

Diagnostic plans

1. Laboratory profile and neurologic examination to assess the presence of pain or underlying organic disease (intracranial disease).

2. Note: Administration of a psychotropic drug as empiric therapy for aggression is not recommended before determining a possible cause and attempting to modify behavior through training.

Aggressive Behavior in the Cat: Differential Diagnosis According to Origin

* These behavior patterns are not necessarily caused by pathologic states. They are characteristic behavior patterns of the species and therefore can be normal. Familiarity with the normal, species-typical aggressive patterns of the cat enables differentiation of species-typical patterns from pathophysiologically based aggression. As with many animal behavior problems, species typicality does not lessen the problem’s disruptiveness or danger.

Blood in urine: hematuria, hemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic plans

1. Thorough history and physical examination, with emphasis on examination of the genitalia, palpation of the prostate, and caudal abdominal palpation.

2. If practical, assessment of urethral patency and the patient’s ability to urinate. Attempt to pass a urethral catheter if significant dysuria and evidence of lower urinary tract obstructions are present.

Differential Diagnosis of Hemoglobinuria

Causes of Apparent or Actual Hematuria in Dogs and Cats Classified by Anatomic Site of Origin

| Site | Diseases |

|---|---|

| Kidney | Pyelonephritis Glomerulonephropathy or glomerulonephritis Neoplasia Calculi Renal cysts Renal infarction |

| Renal trauma Benign renal bleeding Hematuria of Welsh Corgis Dioctophyma renale infection Microfilaria of Dirofilaria immitis Chronic passive congestion | |

| Bladder, ureter, urethra | Infection, inflammation, cystitis, LUTD Cystic calculi Neoplasia Trauma Thrombocytopenia Capillaria plica infection Cyclophosphamide therapy |

| Any site | Coagulopathy Heat stroke DIC |

| Extraurinary sources (genital tract or spurious hematuria) | Prostate Neoplasia Infection Hypertrophy Uterus, pyometra Estrus Subinvolution Infection Neoplasia (including TVT) Vagina Trauma Penis TVT |

DIC, Disseminated intravascular coagulation; LUTD, lower urinary tract disease; TVT, transmissible venereal tumor.

3. Complete urinalysis. Using a fresh sample, include assessment of gross appearance, specific gravity, biochemical reagent strips (dipsticks), and microscopic examination of urine sediment. Ideally, two samples should be collected: a voided urine sample followed by a urine sample collected by cystocentesis.

4. Culture and sensitivity, if bacteria are present.

5. Routine laboratory profile, to include hematology and biochemistry panel.

6. Coagulation profile, if hemoglobinuria is present.

7. Abdominal radiographs, for evidence of calculi, prostatic enlargement, and soft tissue masses.

8. Contrast radiography of the upper and lower urinary tracts.

9. Ultrasound examination of the prostate, urinary bladder, and kidneys.

10. Exploratory laparotomy (if coagulation profile is normal).

Coma: loss of consciousness

Differential diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis of Coma

| Neurogenic | Nonneurogenic | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute, nonprogressive | Intracranial hemorrhage Brain malformations | — — |

| Acute, progressive | Metastatic lesions Epidural, subdural hemorrhage Meningoencephalitis Cerebral edema | Hypoglycemia Diabetic coma (hyperosmotic) Heat stroke Hepatic or uremic encephalopathy Infection Hypoxia Thiamine deficiency (cat) Heavy metal and drug toxicity Carbon monoxide poisoning |

| Chronic, progressive | Hemorrhage (rare) Storage diseases Hydrocephalus Encephalitis | Heavy metal toxicity |

Diagnostic plans

1. Critical: Assessment of vital signs to evaluate airway, breathing, and circulation (pulse, heartbeat, and ECG). Take thoracic radiographs if indicated. If cerebral edema is suspected, administer ventilation support, intravenous hyperosmotic agents (e.g., mannitol 20%, 1 to 2 g/kg of body weight q6h), and glucocorticoids.

2. Conduct careful neurologic examination directed toward evaluation of brainstem function, including motor function, pupillary light responses (or lack thereof), and eye movement.

3. Comprehensive laboratory profile, to include hematology, biochemical profile, and urinalysis.

4. Special diagnostic tests as appropriate:

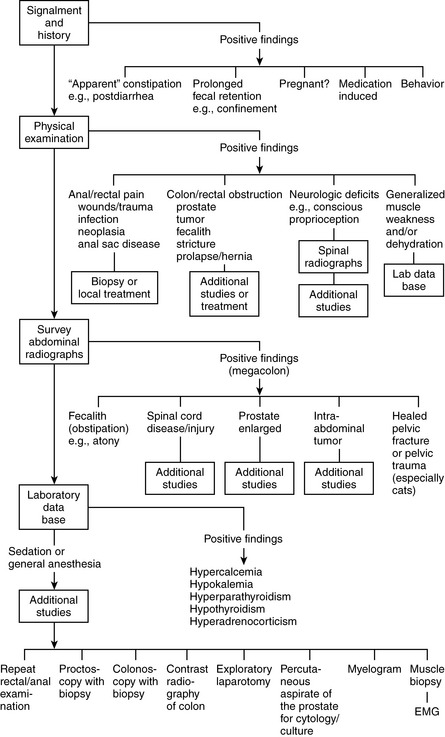

Constipation (obstipation)

See also Straining to Defecate: Dyschezia.

Definition

The owner who perceives a pet as straining to defecate may, in fact, be observing a pet that is straining to urinate. This is particularly true in cats with disorders of the lower urinary tract, such as feline urologic syndrome (FUS). In the context of this discussion, dyschezia is discussed only insofar as it is associated with constipation and obstipation (Figure 3-2).

Cough

Associated signs

Differential Diagnosis of Cough

Primary Respiratory Tract Disease

Canine infectious respiratory disease (CIRD; formerly “kennel cough”); multiple viruses and bacteria may be involved

Tracheal hypoplasia (usually with secondary tracheitis)

Tracheal collapse—acquired and congenital

Tracheal osteochondral dysplasia

Respiratory parasites (e.g., Capillaria aerophila in cats; Filaroides osleri in dogs)

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic plans

1. History and physical examination. Focus on recent exposure risk (boarding) and heartworm preventative in dogs. Physical examination is particularly valuable in determining the extent of respiratory tract involvement and characterizing the type of cough present, particularly when the cough can be elicited by manipulation of the cervical trachea.

2. Careful thoracic auscultation to determine the presence or absence of heart murmur or abnormal lung or airway sounds.

3. Thoracic radiographs using lateral and ventrodorsal projections are critical, particularly when the patient has associated signs compatible with respiratory distress. Oxygen should be available to the dyspneic patient throughout the radiographic procedure. Radiographs should be carefully reviewed for changes in vascular, cardiac, and airway patterns. Patients suspected of having thoracic neoplasia should have left and right lateral thoracic radiographs assessed.

4. A laboratory profile, to include hematology, biochemistry panel, fecal flotation, urinalysis, heartworm test, and feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus (FeLV/FIV) test in the cat.

Coughing blood: hemoptysis

See also Difficulty Breathing.

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic plans

1. Thorough history and physical examination. In addition, an attempt should be made to determine that the sign for which the patient was presented is, in fact, expectoration of blood during coughing and not bloody vomitus.

2. Routine laboratory profile, to assess the patient’s overall health status. Emphasis should be placed on the fecal examination and heartworm tests. Multiple attempts to locate parasite ova in the stool should be made, because lung parasites may be few in number and ova shed intermittently.

3. Thoracic radiographs (especially for evidence of advanced heartworm disease in dogs).

4. Coagulation profile, particularly in those animals with significant bleeding from other sites.

5. Transtracheal aspiration with cytologic studies or bacterial culture and sensitivity tests, or both.

6. Special procedures, including ultrasonography of the lung, particularly when discrete masses are seen on radiographs; echocardiography; blood gas analysis; bronchoscopy; bronchography; and angiography.

7. Radionuclide scans. Although availability is limited, studies may detect areas of pulmonary embolization.

Deafness or hearing loss

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic plans

1. Assessment of response to noise while the animal is relaxed or asleep.

2. Thorough physical examination, particularly of the external ear canal and tympanic membrane.

3. Otoscopic or videoscopic examination in the anesthetized patient.

5. Assessment of thyroid hormone levels.

6. Radiography or computed tomography (CT) of the head, with particular emphasis on the tympanic bullae, for evidence of otitis media.

7. Electrophysiologic studies, including electroencephalography, tympanometry, and brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAER test).

Decreased urine production: oliguria and anuria

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic plans

1. Initiation of fluid therapy and placement of an indwelling urinary catheter, to establish the rate of urine production.

2. History, to address any possible exposure to toxins, particularly antifreeze, as well as recent drug treatment.

3. Radiographs of the abdomen. These may reveal enlarged kidneys, thereby supporting a diagnosis of ARF. Do not rule out the diagnosis of ARF if kidney size appears normal. Ultrasound imaging of kidneys is also helpful in establishing diagnosis.

4. Complete blood count (CBC). The biochemical profile should include electrolytes as well as blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels. Urinalysis (must include urine specific gravity) with microscopic examination of sediment for evidence of crystalluria, RBCs, white blood cells (WBCs), and casts is essential even if only a small volume of urine can be obtained.

5. Blood gases, to assess for metabolic acidosis, which may be severe in ARF.

6. Urine protein-creatinine ratio, to assess proteinuria.

7. If possible, determinations of serum osmolality and serum osmolar gap.

8. Special diagnostics: intravenous pyelogram (IVP), renal biopsy, and determinations of lead and other heavy metals in the blood as indicated.

Diarrhea, acute-onset

Differential diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis for Acute-Onset Diarrhea

Diagnostic plans

1. History and physical examination, including abdominal palpation. Establish possible exposure to infectious agents and associated signs.

2. Intravenous fluids containing NaCl may be a critical part of the early evaluation (signs associated with hypoadrenocorticism or Addison disease may resolve within minutes to hours) in severely dehydrated patients presented with acute diarrhea.

3. Laboratory profile (to include routine hematology), biochemistry profile (to include amylase or lipase and sodium and potassium), urinalysis, examination of feces (direct and flotation). Perform several examinations before ruling out parasitic disease. Cats should be tested for FeLV and FIV. Dogs should be tested for parvovirus antigen in stool.

5. Special diagnostic tests as indicated: abdominal ultrasound; endoscopy and mucosal biopsy; stool culture for viruses or bacteria; serologic studies for rickettsial, viral, and fungal disease; and abdominal laparotomy.

Diarrhea, chronic

Associated signs

Clinical differentiation of small-bowel and large-bowel diarrhea is fundamentally important for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic diarrhea (Table 3-1).

Table 3-1 Clinical Differentiation of Diarrhea of the Small Bowel and Large Bowel

| Clinical Signs | Small-Bowel Diarrhea | Large-Bowel Diarrhea |

|---|---|---|

| Fecal volume | Markedly increased daily output (large quantity of bulky or watery feces with each defecation) | Normal or slightly increased daily output (small quantities with each defecation) |

| Frequency of defecation | Normal or slightly increased | Very frequent: 4-10 times per day |

| Urgency of tenesmus | Rare | Common |

| Mucus in feces | Rare | Common |

| Blood in feces | Dark black (digested) | Red (fresh) |

| Steatorrhea (malassimilation) | May be present | Absent |

| Weight loss and emaciation | Usual | Rare |

| Flatulence | May be present | Absent |

| Vomiting | Occasional | Occasional |

Differential diagnosis

Diagnosis of Specific Chronic Diarrheal Disorders

| Diarrhea | Diagnostic Test or Procedure |

|---|---|

| Small-Bowel Type | |

| Exocrine, pancreatic insufficiency | Serum trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) |

| Chronic inflammatory small bowel disease | |

| Eosinophilic enteritis | Eosinophilia, biopsy |

| Lymphocytic-plasmacytic enteritis | Biopsy |

| Serum protein electrophoresis | |

| Immunoproliferative enteropathy of Basenjis | Radiography, biopsy |

| Granulomatous enteritis | |

| Lymphangiectasia | Lymphopenia, intestinal biopsy, and total protein and lymphocyte count |

| Villous atrophy | |

| Gluten enteropathy Idiopathic | Response to gluten-free diet Biopsy |

| Histoplasmosis | Serology, cytology, biopsy |

| Lymphosarcoma | Biopsy and cytology |

| Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) | Culture of intestinal aspirate, folate, response to antibiotics |

| Giardiasis | Fecal examinations, response to parasiticides |

| Lactase deficiency | Response to lactose-free diet |

| Large-Bowel Type | |

| Chronic colitis | Colonoscopy, colon biopsy (multiple samples are required) |

| Idiopathic Histiocytic Eosinophilic | |

| Whipworm colitis | Fecal flotation, colonoscopy, response to fenbendazole |

| Protozoan colitis | Saline fecal smears |

| Amebiasis Balantidiasis Trichomoniasis | |

| Histoplasma colitis | Fecal cytology, colon biopsy, serology, culture |

| Salmonella colitis | Culture |

| Campylobacter colitis | Culture |

| Prototheca colitis | Colon biopsy |

| Tritrichomonads | |

| Rectocolonic polyps | Digital palpation, barium enema |

| Colonic adenocarcinoma | Colonoscopy, barium enema, possibly abdominal ultrasound |

| Colonic lymphosarcoma | Barium enema, colonoscopy |

| Functional diarrhea (irritable colon) | History, diagnostic workup excludes all other diseases |

Diagnostic plans

1. Clinical history and physical examination findings, to classify the diarrhea as small bowel or large bowel. Routine patient screening should include hematologic studies, biochemical profile, fecal flotation and direct examination, and urinalysis.

2. Diagnosis of intestinal parasites. Perform a visual examination of the feces and anus for proglottids, a zinc sulfate flotation test for Giardia and Coccidia cysts, a saline suspension for protozoan trophozoites, and a sedimentation or Baermann determination for Strongyloides larvae. Adult whipworms can be seen in the colon on colonoscopy.

3. Additional fecal studies. Beyond routine fecal flotation and direct examination, several other fecal tests are indicated, including microscopic examinations for fat (Sudan preparation), starch (iodine preparation), and cytologic staining (Gram stain and Wright stain) to assess for presence of leukocytes and infectious agents. Malassimilation can be assessed through quantitative fecal fat analysis and fecal weight (daily output), although in clinical practice these tests are seldom performed. Several special biochemical and physical tests can also be carried out on feces: fecal water content, nitrogen content (for azotorrhea and malassimilation), electrolytes, pH, osmolality, fecal occult blood, and cultures for both fungi and bacteria.

4. Tests of absorptive and digestive function, such as trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI), serum folate, and vitamin B12 assay.

5. Gastrointestinal (GI) radiography and ultrasonography.

6. GI endoscopy (gastroscopy, duodenoscopy, and colonoscopy), with biopsy of intestinal mucosa. Duodenal intubation and aspiration can be performed to obtain specimens for cytologic examination and culture.

7. Exploratory laparotomy and intestinal biopsy.

8. Response to empiric treatment: Enzyme replacement or treatment of occult parasite infections.

Difficulty breathing or respiratory distress: cyanosis