CHAPTER 24 Materia Medica

INTRODUCTION

The monographs in this chapter are organized in the following way:

This is the most common name, as indicated in Herbs of Commerce (McGuffin, 2000), the official authority recognized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and by the Therapeutic Goods Administration, the group that regulates medicine in Australia.

All parts of the plants used for medicine (and in most cases, those used for food) are listed.

We have elected to include the more individually unique constituents here, as opposed to listing every possible constituent that may occur in a plant. Be aware that in plant medicine, no one constituent can be singled out as “the active constituent,” and, even if all of the vitamins, minerals, proteins, fixed fats, and sugars in a plant are not listed, these are important active constituents as well.

History and Traditional Usage:

Chapter 5 contains more detailed information to which this subheading refers. Briefly, energetics describes the taste of the herb and the end clinical effects that it has on patients, according to traditional understanding of the herb. Energetic characteristics may include reference to Heat, Damp, Cold, and Phlegm, and to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) organs such as Spleen, Liver, Kidney, Heart, and Stomach; reference is not made to Western medicine organs of the same name.

These indications are based on solid traditional uses and evidence-based findings.

Suggested Veterinary Indications:

This section contains various points of interest, such as historical minutiae and conservation status. Maude Grieve’s book, A Modern Herbal, contains many interesting historical and botanical notes and is available online at www.botanical.com. For more information on invasive species, see www.invasive.org. For information on threatened or endangered species, see the following Web sites:

Contraindications; Toxicology and Adverse Effects; Drug Interactions:

Aside from information on commonly recognized effects found in the general literature on any specific herb, two primary references were used for this section. The Botanical Safety Handbook, published by the American Herbal Products Association, is an important collection of safety grades that was published in 1997. The grading system used was based on a critical review of world literature and is defined as follows:

Similarly, a general rule for small animals is 0.5 to 1.5 mL per 10 kg (20 lb) total daily dose, divided into two or three doses (assuming a 1 : 2 to 1 : 3 tincture). A total daily dose of a multiple herbs in a formula can be calculated by selecting a dose in the the given range for each herb and adding all doses together. Select the higher dose for herbs with the primary desired action or effect. Then, simply multiply the individual herb volume by the number of doses needed to arrive at the formula; round up or down to make dispensing easy. For example, if the daily dose for an herb is 0.5 to 1.5 mL daily for a 10-kg dog, the prescriber will, for instance, select 1 mL. For 14 doses (or 2 weeks of treatment), 14 mL is required, which can be rounded up to 15 mL. If the patient is 20 kg, you will need 30 mL in the formula. Infusions are made as for humans (5-30 g per cup of water) and administered at a rate of ½ cup to 1 cup per 10 kg (20 lb) per day, divided and added to meals or given by mouth. Dried herb extracts (assuming they have been extracted, then dried) are generally between 25 and 75 mg per kg per day, but this depends on the individual product. For simple dried herb, up to 4 times this dose may be indicated.

If the practitioner lacks experience with a particular herb, it is wise to start with the lowest recommended dose and increase slowly (to the higher dose in the range). Experienced herbalists may use much higher doses for specific herbs than given here for various reasons. In general, a formula with mutiple herbs is dosed at the lower end of the range for individual herbs (so that the total volume is easy to administer and to take into account synergy). When in doubt, the prescriber should counsel owners that the initial dose is a low starting dose, and that if no results are seen within a few days to a week, the dose may be increased. Chapter 14 provides additional information on dose calculation and administration of herbs.

Bone K. A Clinical Guide to Blending Liquid Herbs. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone, 2003.

Brinker F. Complex Herbs, Complete Medicines. Sandy, Ore: Eclectic Medical Publications, 2004.

Evans WC. Trease and Evans Pharmacognosy, 15th edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002.

Felter HW, Lloyd JU. King’s American Dispensatory (1898). Available at: http://www.henriettesherbal.com (provided free on the Web on Henriette Kress’s Herbal Homepage).

Grieg JR, Boddie GF. Hoare’s Veterinary Materia Medica and Therapeutics, 6th edition. London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, 1942.

Grieve M. A Modern Herbal (1931). New York: Barnes and Noble Books; 1996. Also available online at www.botanical.com.

Herr SM. Enst E, Young VSL, editors. Herb-Drug Interaction Handbook, 2nd ed., Nassau, NY: Church Street Books, 2002.

Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism. Rochester, Vt: Healing Arts Press, 2003.

Karreman H. Treating Dairy Cows Naturally: Thoughts and Strategies. Paradise, Pa: Paradise Publications, 2004.

Kirk H. Index of Treatment in Small-Animal Practice. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins, 1948.

Kuhn M, Winston D. Herbal Therapy and Supplements: A Scientific and Traditional Approach. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2001.

Marsden S. Foundations in Formula Design: Achieving Balance and Synergy with Western Herbs. Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Department of Classical Chinese Medicine, National College of Naturopathic Medicine, Portland, Ore, 2000.

McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, et al. Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, 1997.

McGuffin M, Kartesz JT, Leung AY, et al. Herbs of Commerce, 2nd edition. Silver Spring, Md: American Herbal Products Association, 2000.

Milks HJ. Practical Veterinary Pharmacology, Materia Medica and Therapeutics, 6th edition. Chicago, Ill: Alex Eger, Inc, 1949.

Mills S, Bone K. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Moerman DE. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland, Ore: Timber Press, 1998.

Skenderi G. Herbal Vade Mecum: 800 Herbs, Spices, Essential Oils, Lipids, Etc. Constituents, Properties, Uses and Caution. Rutherford, NJ: Herbacy Press, 2004.

Tierra M. Planetary Herbology. Twin Lakes, Wis: Lotus Press, 1988.

Van Wyk B-E, Wink M. Medicinal Plants of the World: An Illustrated Scientific Guide to Important Medicinal Plants and Their Uses. Pretoria, South Africa: Briza Publications, 2004.

Weiss RF. Herbal Medicine, Translated from the German 6th edition. Beaconsfield, England: Beaconsfield Publishers, Ltd, 1994.

Wichtl M. Bisset NG, editor. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuti-cals: A Handbook for Practice on a Scientific Basis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, 1989. (English language edition, 1994.)

Williamson EM. Major Herbs of Ayurveda. United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Winslow K. Veterinary Materia Medica and Therapeutics, 6th edition. New York: William R. Jenkins Co, 1909.

Yarnell E. Clinical Botanical Medicine. Larchmont, NY: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc, 2003.

Agrimonia eupatoria • Agim-MOH-nee-uh yew-pat-TOH-ree-uh

Energetics: Slightly bitter, astringent, warm; affects primarily lung, liver, spleen (Tierra)

History and Traditional Usage: Grieve (1931) claims that sheep and goats eat the plant, but cattle, horses, and swine do not. Used since medieval times for wounds of all sorts and snakebites, this plant is an astringent antidiarrheal. Native American tribes used a native species (Agrimonia gryposepala) for similar purposes when astringents were called for—for diarrhea, for skin eruptions, as a styptic, and so forth. It has been used for a “relaxed throat” (in physiomedical philosophy) and has been used since the time of Dioscorides for liver problems. This astringent is also used for cystitis and urinary incontinence. Agrimony is considered when copious mucous secretions emerge from any mucous membrane.

Contraindications: Pregnancy and lactation are usually listed as contraindications.

Dried herb: 1-10 g TID, up to 6 times daily for acute conditions

Dried herb: 25-300 mg/kg divided daily (optimally TID)

Albizia![]()

Albizia lebbeck [L.] Benth. • Al-BIZ-ee-uh LEB-ek

Other Names: Siris, siris tree, albizzia, pit shirish

Parts Used: Stem bark, leaves, and seeds (flowers also used)

Selected Constituents: Saponins, cardiac glycosides, tannins, flavonoids

Clinical Actions: Antiallergic, antimicrobial, anticholesterolemic

History and Traditional Usage: It has been used for bronchitis, leprosy, paralysis, and helminth infections and by Ayurvedic physicians for bronchial asthma and eczema. Albizia seeds have been used in the treatment of patients with diarrhea and dysentery. The leaves are nutritious and palatable and can be used as fodder.

Published Research: Albizia has antidiarrheal activity, which supports the historical use of the seeds in the treatment of patients with diarrhea and dysentery. An extract potentiated the activity of loperamide (1 mg/kg intraperitoneally [ip]). Naloxone (0.5 mg/kg ip) significantly inhibited the antidiarrheal activity as well as the loperamide did, suggesting a role in the opioid system (Besra, 2002). Albizia has some nootropic activity involving monoamine neurotransmitters (Chintawar, 2002). The antiallergic activity of albizia was investigated, showing a significant action on mast cells and inhibiting early sensitization and synthesis of reaginic-type antibodies. The active ingredients of the bark appear to be heat stable and water soluble (Tripathi, 1979).

Potential Veterinary Indications: Allergic bronchitis, allergic skin disease, mast cell tumors

Potential Drug Interactions: Caution with inotropic heart medications—may be synergistic

Tincture: 1 : 2 or 1 : 3: 1-5 mL TID

Dried herb: 25-200 mg/kg, divided daily (optimally TID)

Besra SE, Gomes A, Chaudhury L, Vedasiromoni JR, Ganguly DK. Antidiarrhoeal activity of seed extract of Albizzia lebbeck Benth. Phytother Res. 2002;16:529-533.

Chintawar SD, Somani RS, Kasture VS, Kasture SB. Nootropic activity of Albizzia lebbeck in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;81:299-305.

Tripathi RM, Sen PC, Das PK. Studies on the mechanism of action of Albizzia lebbeck, an Indian indigenous drug used in the treatment of atopic allergy. J Ethnopharmacol. 1979;1:385-396.

Alfalfa![]()

Medicago sativa L. • Med-DIK-ah-go sa-TEE-vuh

Other Names: Lucerne, luzerne, Spanish clover

Parts Used: Leaf used medicinally. Sprouted seeds used as food.

Energetics: Sweet, pungent, cool; nourishes Yin, moistens dryness (Marsden)

History and Traditional Usage: Used mostly as food.

Published Research: No relevant clinical trials found.

Preparation Notes: Dried herb usually has a very acceptable taste to dogs and cats.

Dried herb: 50-500 mg/kg, divided daily (optimally TID)

Aloe perryi Baker (socotrine aloes)

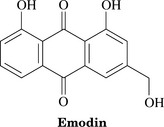

Parts Used: Aloe vera gel is the viscous, colorless, trans-parent liquid from the inside of the leaf. Aloe vera juice arises from juice in the cells of the pericycle and adjacent leaf parenchyma and flows spontaneously from the cut leaf; it is usually dried. To obtain aloe gel, the leaf is processed and aloin is removed. The cape aloes preparation consists of dried latex from bundle sheath cells within the leaf, which is high in hydroxyanthrone derivatives of aloe emodin (such as aloin) and is the source of laxative preparations.

Constituents: Aloe vera gel consists primarily of water and polysaccharides (glucomannan, acemannan, mannose derivatives, pectin, hemicelluloses), as well as amino acids, lipids, sterols (campesterol, B-sitosterol, lupeol), and enzymes (Bruneton, 1995). Mannose-6-phosphate is a major sugar component (Davis, 1994). Cinnamoyl, p-coumaroyl, feruloyl, caffeoyl aloesin, and related compounds have been isolated from Aloe species. Aloe latex contains as its major and active principles hydroxyanthrone derivatives (Bruneton, 1995).

Clinical Actions: Demulcent, vulnerary, stimulant laxative

Energetics: Gel slightly bitter; juice sour and very bitter

Modern clinical use of the gel began in the 1930s, with reports of successful treatment of x-ray and radium burns, which led to additional experimental studies that used laboratory animals in subsequent decades (Grindlay, 1986).

Modern veterinary usage was first reported in 1975 (Northway, 1975); however, in Europe, it was a popular ingredient of physic balls and was used in combination with ginger as a purgative for horses; it was used for horses that were coming off grass to undergo training. It was also a common ingredient in “condition” balls used to condition a horse for training, to aid assimilation of food, to improve skin, and to help condition the coat. Also used for the treatment of colic in horses (RCVS, 1920). In dogs, aloe was incorporated into “alterative balls” and condition pills (RCVS, 1920). Milks (1949) recommended aloe for whenever a “good brisk cathartic” is required, for instance, in “colic, hidebound, overloaded stomach or bowels, to expel worms after a vermicide, to promote excretion of waste products from the bowels and blood,” or as a tonic. He also recommended it to stimulate wound healing and suggested that ruminants were less sensitive to it than horses, and that dogs and cats required as much as 5 to 10 times the dose a human should take!

It has been advocated for the treatment of farm animals with constipation, indigestion, worms, and urinary ailments and externally for the cure of corneal ulcers and keratitis (de Bairacli Levy, 1963). Aloe was used as a purgative for horses; it was also used in veterinary practice as a bitter tonic (in small doses) and “externally as a stimulant and desiccant” (Grieves, 1931). Aloe nuttii has been used to treat Newcastle’s disease in poultry, worms, and dystocia; Aloe perfoliata has been used to treat pneumonia in livestock (Kambewa, 1997). Aloe vera is one of four major medical plants used to treat health problems in poultry in Trinidad and Tobago (Lans, 1998).

Laxative effect

Aloe’s laxative mechanism of action is twofold. The juice (not the gel) stimulates colonic motility, augmenting propulsion and accelerating colonic transit, which reduces fluid absorption from the fecal mass and increases the water content in the large intestine (de Witte, 1993). The laxative effects are due to the glycosides aloin A and B (formerly known as barbaloin). These are hydrolyzed in the colon by intestinal bacteria and then reduced to active metabolites, which act as stimulants and irritants to the GI tract. The laxative effect of aloe is generally not observed before 6 hours after oral administration, and sometimes not until 24 hours or longer after administration (WHO, 1999).

Wound healing activity

Other mechanisms of action include the hydrating, insulating, and protective properties of the gel (Bruneton, 1995). The gel inhibits thromboxane A2, a mediator of progressive tissue damage (Davis, 1994) produced in burned dermal tissue and pressure sores (Swaim, 1987, 1992). Angiogenesis is essential in wound healing, and the gel has been shown to be angiogenic (Moon, 1999). The constituent allantoin enhances epithelialization in suppurating wounds and resistant ulcers (Swaim, 1992). Another constituent, acemannan, stimulates macrophages to produce the cytokines interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor, which, in turn, stimulate angiogenesis, epithelialization, and wound healing (Cera, 1980). It also has anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities because of the presence of a salicylate-like substance (Swaim, 1987).

The effects of topical aloe gel have been compared with the therapeutic effects of systemic pentoxifylline in the treatment of frostbite on the ears of 10 New Zealand white rabbits. Pentoxifylline improved tissue survival (20%), as did aloe vera cream (24%), and the combination of both was best (30%) (Miller, 1995). Another study showed a 62.5% reduction in wound diameter in mice (with induced biopsy punch wounds) that received 100 mg/kg/day oral aloe, and a 50.8% reduction was recorded in animals that were given topical 25% aloe. These data suggest that aloe is effective through both oral and topical routes of administration (Davis, 1989).

Swaim (1992) compared the effects of aloe vera gel with those of triple antibiotic ointment on footpad wounds in dogs. Beagles were anesthetized, and a full-thickness 0.7-cm square defect was incised on one pad of each rear limb. In 12 dogs, one defect was treated with a dressing of aloe vera gel, and the other was treated with a dressing of triple antibiotic ointment. Three control dogs received no treatment. Monitoring of wound size occurred on days 7, 14, and 21. Although no differences were observed in wound size on days 14 and 21, the aloe-treated wounds were smaller on day 7. Compared with outcomes in controls, both treatments resulted in faster healing at day 14; however, control wounds were equivalent in size to treated wounds by day 21. Investigators concluded that aloe vera gel appears to stimulate early wound healing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree