CHAPTER 21 Herbal Medicine in Equine Practice

1000 ad—That root is heathen. Here, say this prayer.

1850 ad—That prayer is superstition. Here, drink this potion.

1940 ad—That potion is snake oil. Here, swallow this pill.

1985 ad—That pill is ineffective. Here, take this antibiotic.

2000 ad—That antibiotic is artificial. Here, eat this root.

CURRENT USE OF HERBS IN EQUINE PRACTICE

Client Considerations

Horse compliance is as important as client compliance. Some horses will not eat herbs under any circumstances; others will eat them with inducement. In this author’s opinion, a horse’s refusal to eat herbs may mean that the formula is not correct. If a formula is not eaten, the case is revisited and a new formula selected. In most instances, the horse will eat the correct formula. An example of how this works was demonstrated by a mare that had been on a formula to help regulate her heat cycles. The formula contained valerian root (Valeriana officinalis). The mare experienced mild colic, and after the colic passed, she completely refused to eat the original formula. The valerian was removed because it was the only herb in the formula known to possibly have an adverse effect on the intestinal tract; after that, the mare consumed the rest of the herbs. Valerian is considered to be a safe herb with relaxing and intestinal antispasmodic action. It is also known for producing paradoxical effects (Holmes, 1997; Tilford, 1999). This author has seen several clinical gastrointestinal cases in which valerian was fed over a long time. Removal of valerian cleared all cases. It is also a strong smelling herb which may deter some patients from eating it voluntarily.

EQUINE ZOOPHARMACOGNOSY

The field of zoopharmacognosy is expanding, as the interest in herbs is growing (Engel, 2002). This is the study of how animals self-select plants and other materials such as minerals, possibly in order to address disease or discomfort. Animal behaviorists, ecologists, pharmacologists, anthropologists, geochemists, and parasitologists have all contributed to this truly multifaceted discipline (Biser, 1998; Buchanan, 2002).

Most owners have noticed that horses rarely eat the rich grass next to feces. Research has shown that many domestic species avoid parasites as they graze. For example, sheep avoided eating patches of vegetation with higher fecal burdens than were found in uncontaminated patches. Further study has shown that sheep avoid the consumption of grass infected with larvae, even though it may offer them higher intake rates (Hutchings, 1999). This is particularly the case for animals that are naive to parasites. Also, hungry animals are more likely to eat at the expense of larval ingestion. These studies appear to demonstrate that domestic animals might assess the costs, as well as the benefits, of their foraging decisions.

One study of ponies showed that they apparently are able to learn a taste aversion—although incompletely (Houpt, 1990). Illness was created with the use of apomorphine when the pony ate one type of feed (corn, alfalfa pellets, sweet feed, or a complete pellet) when other feeds were offered simultaneously. Ponies learned to avoid all feeds except the complete feed when apomorphine injection immediately followed consumption of the feed. However, they did not learn to avoid a feed when apomorphine was delayed for 30 minutes after feed consumption. They could learn to avoid alfalfa pellets, but not corn, when these feeds were presented with the familiar “safe foods”—oats and soybean meal. This study demonstrated that ponies have some ability to distinguish between safe and unsafe foods.

Yet the modern horse owner assumes that horses require grass. When horses (that evolved to survive in relatively tough conditions) are placed in rich, lush, and fertilized fields without adequate exercise, they frequently become overweight and unfit. Other wild animals have been observed to become fat and unhealthy when they are given access to too much rich, unnatural food; it is easy to picture what would happen if the bears and monkeys in every national park were given access to junk food (Sapolsky, 1989).

Historically, it was recognized that “as regards to exercise, it is indispensable. No man or horse can ever enjoy good health unless habituated to daily exercise; it tends toward their health and strength, assists and promotes a free circulation of the blood, determines morbific matter to the various outlets, develops the muscular powers, creates a natural appetite, improves the wind, and finally invigorates the whole system” (Dadd, 1854). Medicine should not be given to prevent disease; “health is best preserved by the proper regulation of diet, exercise, and cleanliness” (Lawson, 1824). One of the fastest growing equine health problems is obesity and its associated illnesses.

Horses kept in fields will preferentially eat the grasses and legumes most of the time. However, horses grazing in a pasture in which a selection of plants is provided will eat a greater variety. At certain times of the year, for example, the tops of the yarrow in this author’s field are eaten. Whether these are eaten by horses or by deer has yet to be determined. When horses are removed from the field and are allowed to graze along the fence rows, yarrow is sometimes eaten and sometimes not. Dandelions are always eaten in the spring—but only occasionally at other times of the year. Most horses crave spring dandelions, and some will eat the dirt while trying to get at the roots, especially if they have been ill through the winter (Figure 21-1).

However, if domestic horses are raised in an artificial environment—exposed only to rich monoculture grass—it is possible that those horses will not instinctively know enough to self-medicate. Zoopharmacognosy researchers have tested the theory that animals learn which plants to eat by watching others of the same species (Huffman, 2001). Thus, a wild horse or a domesticated horse that has been raised with a natural, varied diet may be adept at determining which plants it should eat. These factors would need to be considered in research.

Author observation and information from toxicologists indicate that horses will not eat most toxic plants if they are well fed and do not graze in overcrowded pastures (Knight, 2001). Most poisonings occur when animals are exposed to unfamiliar plants, or when little safe plant material is available to graze. Certain plants such as red maple (Acer rubrum) and cherry (Prunus spp) become extremely toxic when the leaves are wilted. Domestic horses will often eat the wilted leaves; however, in most cases of poisoning, pasture overstocking has been found. Certain ornamental plants such as Yew may be unfamiliar enough to horses that they will eat them. Horses starved for green forage, as most confined horses are, will often eat indiscriminately anything green. Many “weeds” growing in barnyards are medicinal herbs or toxic plants; the vast majority of horses will never eat the toxic ones.

Ranching and grazing researchers have studied details about the grazing habits of livestock. Investigators examined which grasses were most palatable, and when they were most likely to be eaten (Fehmi, 2002). If given a choice of grasses to eat, cattle will select only what is at the peak of nutritive value and will leave the rest until it reaches peak. This indicates that cattle can make decisions about what is best to eat. Peak nutrition varies according to type of grass, season of the year, and climatic conditions. Research such as this does not show that animals are self-medicating, but rather that they recognize differences in the grasses they eat.

McClure wrote that horses should most often be fed hay if they are not being worked; corn and oats can be fed when they are working. Vetches and cut grass should be fed to horses that cannot graze in the spring. He believed that vetches and grass had cooling and refreshing qualities that were almost medicinal in effect (McClure, 1917).

Most modern horses have no idea what a day’s work is; many are ridden less than an hour at a time and only a few days a week. They are fed large quantities of processed grain while they stand in a small stall or pen. In nature, horses walk about 20 hours a day and sleep less than 4 hours (Pascoe, 2000). Many modern stabled horses are almost never fed fresh greens—a fact that has increased the incidence of vitamin E deficiency diseases such as equine motor neuron disease, as well as fertility problems (Divers, 2003).

DRUG TESTING AND HERBS

Equine veterinarians working with competition horses may be asked whether a specific herb or formula will cause a positive drug test. Practitioners are responsible for any positive tests if they prescribe or approve an herb, and they should be cautious. No set answer exists regarding which herbs are legal because new tests are devised regularly. Any list published here or on any Web site should be considered partial. Positive test results are possible with herbs, so practitioners should consult with manufacturing companies and drug testing laboratories for advice. If there is any question, it is better to withdraw the herb rather than risk a positive drug test.

Herbs that contain salicylates such as white willow bark (Salix alba) and others that can be sold under the name of white willow—crack willow (Salix fragilis), purple willow (Salix purpurea), and violet willow (Salix daphnoides), along with meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) Betula (birch) spp, Populus (poplar) spp, and bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus)—have strong potential for producing a positive drug test. Salicylic acid is illegal in competition. Metabolism of plant-based salicylic acid precursors has not been studied in horses; however in humans these compounds undergo hepatic conversion into salicylic acid. It is unknown whether the concentration of salicylic acid precursors in these herbs are great enough to create a positive test. Willow bark and meadowsweet are the only herbs containing salicylates that are specifically listed as forbidden (United States Equine Federation, 2005).

The guidelines that are available for compounds that may cause a positive drug test state, “Any product is forbidden if it contains an ingredient that is a forbidden substance, or is a drug which might affect the performance of a horse and/or pony as a stimulant, depressant, tranquilizer, local anesthetic, psychotropic (mood and/or behavior altering) substance, or might interfere with drug testing procedures (USEF, 2005).” These regulations also provide “… just some of the examples of the hundreds and perhaps thousands of examples of herbal/natural or plant ingredients that would cause a product to be classified as forbidden …,” indicating that in the future, possible testing may be available for any herb. Herbs specifically listed as prohibited in the United States are included in Table 21-1. In Australia, listed prohibited herbs include white willow, kola, kava, guarana, and valerian, but other herbs may be tested for. Chinese herbs with known compounds that can test positive are listed in Table 21-2 (Xie, 2003). Other Chinese herbs may consist of similar compounds but are not specifically listed as prohibited.

TABLE 21-1 Herbs Specifically Prohibited in Competition in the United States

| Common Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|

| Arnica, wolfsbane | Arnica montana |

| Cayenne (capsaicin, derivative) | Capsicum annuum |

| Chamomile (species is not specified in regulations) | Matricaria spp, Ormenis mixta/multicola, Anthemis nobilis |

| Comfrey | Symphytum officinale |

| Devil’s claw | Harpagophytum procumbens |

| Hops | Humulus lupulus |

| Kava kava | Piper methysticum |

| Laurel | Laurus nobiles |

| Lavender | Lavandula spp |

| Lemon balm | Melissa officinalis |

| Leopard’s bane (listed in regulations under this name), Arnica | Arnica montana |

| Night shade | Solanum spp |

| Passionflower | Passiflora incarnata |

| Rauwolfia | Rauvolfia serpentina |

| Red poppy | Papaver rhoeas, P. somniferum |

| Skullcap | Scutelleria lateriflora |

| Valerian | Valeriana officinalis |

| Vervain | Verbena officinalis |

TABLE 21-2 Chinese Herbs That May Be Forbidden in the Racing Community in the United States

| Herb | Chinese Name | Substances Forbidden by Rules |

|---|---|---|

| Ephedra | Ma huang | Ephedrine |

| Papaver | Yin su ke | Morphine |

| Strychnos | Ma qian zi | Strychnine |

| Datura | Yang jin hua | Atropine |

| Acacia | Er cha | Theophylline |

From Xie, 2003.

QUALITY CONTROL ISSUES

Because of the large volume of herbs needed to treat even one horse, the temptation may be great for a company to use less-than-ethically harvested herbs. Herb quality and manufacture is as important today as it was in the past. Even in 1843, Youatt warned herbalists to stay away from powdered ginger because it was usually adulterated with bean meal or sawdust, then was made warm and pungent with capsicum; he recommended purchasing the whole root and grinding it (Youatt, 1843). To this day, the natural products industry is largely unregulated, and many poor-quality products are sold (Butters, 2003). A company without much knowledge of herbs can easily purchase poor-quality products without even being aware of it. The reader is referred to Chapter 17 on sustainable harvesting and endangered species, as this is another very important issue.

In the United States, practitioners who must find out which companies are committed to quality control should contact the National Animal Supplement Council (National Animal Supplement Council, 2005). This is an alliance of companies dedicated to quality control and self-regulation and opposed to unnecessary government regulation. These companies work to raise the standards within an industry that often profits from the use of poor-quality raw materials. No such industry alliances have yet been formed in other parts of the world, to this author’s knowledge.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

An adverse or toxic reaction to a substance occurs when an unfavorable, harmful, destructive, or deadly outcome occurs (Brown, 2001). An adverse or toxic reaction is one that is known to occur with the administration of a particular substance, for example, diarrhea after the administration of aloe. An idiosyncratic reaction is one that occurs when a compound that is routinely safely administered causes unique symptoms in one individual, for example, hives after the administration of meadowsweet.

Because no database is available widely to document adverse events related to herbal medicine in the equine, it may be impossible for a practitioner to know whether an herb is responsible or some unique reaction has occurred. VBMA (Veterinary Botanical Medicine Association) has the facility to record reported cases and is available at www.vbma.org. Consultation with an experienced equine herbalist may be helpful. In all cases, when any adverse event occurs, possible contributing factors such as concomitant drugs, diet and doses should be recorded. The product should be discontinued immediately. If the clinical sign subsides rapidly and was mild when it occurred, the product may be administered again at a lower dose after a week; if the sign then recurs, the product should be discontinued completely.

CAUTIONS WITH HERBS

False Information

Old wives’ tales are abundant in equine practice and in the literature. In England and Australia particularly, flax (Linum usitatissimum) is considered toxic unless it is well cooked. Flax does contain cyanogenic glycosides; however, the quantity is small and no clinical symptoms have resulted when it is fed at high levels for long periods (personal experience, and Knight, 2001). Horses, because of their acid stomachs, are rarely affected by any type of cyanide poisoning (Knight, 2001). Even when cattle are fed the raw cake (by-product of linseed manufacturing), 10 minutes’ boiling time is all that is needed, contrary to some claims that it must be boiled for an extended period in preparation for equine consumption.

Many claims have also been made about the toxicity of garlic (Allium sativum). Garlic has the potential for toxicity in dogs and especially in cats. The toxic compound is N-propyl-disulfide, and some evidence in the literature supports the claim of toxicity (Knight, 2001). One equine case of urticaria associated with dry garlic feeding has been reported (Miyazawa, 1991). A few reports can be found in the literature regarding onion toxicity in the bovine. Acute hemolytic anemia caused by wild onion poisoning was reported in horses (Pierce, 1972). No significant toxicities have been reported for garlic specifically, although a few practitioners believe that they have seen horses that have become anemic through chronic ingestion of garlic.

Internal

When black walnut (Juglans nigra) is given, a substance in the wood shavings or the heartwood can cause laminitis (Uhlinger, 1989; Minnick, 1987). Oral administration of the seed and bark appears safe clinically. The constituent juglone, which has been thought to be the cause of the laminitis, is present in the bark and nuts—but not in the heartwood, so juglone is probably not the poisonous principle (Knight, 2001). Although some practitioners believe it is safe to feed the seeds and bark, in this author’s opinion, the risk is too great to make the chance worth taking. Other anthelmintic herbs are available as alternatives to black walnut.

PREGNANCY

A number of herbs are contraindicated in pregnancy because (1) they have the potential to cause uterine contractions, such as black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa), (2) they may alter hormones in a manner that can result in risk to the pregnancy, such as fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) (Gruenwald, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000), or (3) they are teratogenic, such as comfrey (Symphytum officinale) (Gruenwald, 2000; Brinker, 2000) (Table 21-3). Because no specific research has been undertaken to investigate the equine, it is best for the practitioner to assume that an herb that is specifically contraindicated for use in pregnancy in humans or other species because of known biochemistry should not be used in the equine.

TABLE 21-3 Some Common Herbs Contraindicated in Pregnancy

| Plant | Clinical Result* |

|---|---|

| Chaste Berry (Vitex agnus-castus) | Uterotropic effects, emmenagogue (DerMarderosian, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000) |

| Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) | Uterine stimulant, spontaneous abortions; except in 1st trimester—may decrease uterine spasms, antiabortive, hormonal effects (DerMarderosian, 2000; Gruenwald, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Burdock (Arctium lappa) | Uterine stimulant, especially first trimester, oxytocic effects (Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla or recutita) | Possible abortifacient in early pregnancy, emmenagogue (Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000; DerMarderosian, 2000); claims that there are no contraindications in pregnancy |

| Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) | Teratogenic, mutagenic, fetotoxin, chromosome damage to human lymphocytes (DerMarderosian, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) | Oxytocic action, emmenagogue, abortifacient (DerMarderosian, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Garlic (Allium sativum) | Large doses can serve as uterine stimulant, emmenagogue effects (DerMarderosian, 2000; Gruenwald, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) | Uterine stimulant, equivocal data for pregnancy complications, emmenagogue (Blumenthal, 2000) |

| Lavender (Lavendula angustifolia) | Emmenagogue (Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000; DerMarderosian, 2000; Gruenwald, 2000) |

| Parsley fruit (Petroselinum crispum) (roots and leaves are safe) | High doses increase contractility of smooth muscle—abortifacient. Low doses increase uterine tone; could be emmenagogue (DerMarderosian, 2000; Brinker, 2000; Gruenwald, 2000) no stated problem |

| Red clover (Trifolium pretense) | Estrogenic activity possible (Brinker, 2000) |

| Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) | Can be used externally during pregnancy. Contains volatile oils; contraindicated in pregnancy because of uterine stimulation, emmenagogue, abortifacient (Gruenwald, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Sage (Salvia officinalis) | Emmenagogue (alcohol extract and essential oil) (Blumenthal, 2000); abortifacient, uterine stimulant (Gruenwald, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Thyme (Thymus vulgaris) | Emmenagogue, early pregnancy (DerMarderosian, 2000; Gruenwald, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Turmeric (Curcuma longa, aromatica) | Emmenagogue, abortifacient, uterine stimulant (DerMarderosian, 2000; Gruenwald, 2000; Blumenthal, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

| Wormwood tops, leaves (Artemisia absinthum) | Emmenagogue, abortifacient, uterine stimulant (possible) (Brinker, 2000) |

| Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) | Emmenagogue, abortifacient, uterine stimulant (possibly only some constituents) (DerMarderosian, 2000; Gruenwald, 2000; Brinker, 2000) |

* This is not a complete listing of all herbs known to have effects on pregnancy, but it includes most of the ones commonly used in equine practice.

HERB/DRUG INTERACTIONS

At the present time, very little, if any, research has been conducted in the equine concerning herb/drug interactions and adverse reactions. However, it is possible and desirable for the practitioner to examine the data collected for other species and to at least consider that they may be applicable to the horse (Brinker, 2001; Harman, 2002). This is especially true for herb/drug interactions because the drugs used in horses have similar biochemical effects in other species. Some of the adverse reactions seen in other species may not occur in the equine because the digestive tract is designed to handle a large variety of plant material.

PRACTICAL USES OF HERBS

Horses are more sensitive to, and require smaller quantities of, many food and drug items per pound of body weight than are small animals with a higher metabolic rate. This is true of many larger species of animals. Dosing in modern times has been based on experience and extrapolation from the old texts. However, doses derived according to McClure in 1917 were also empirical and approximate and were determined without a specific reason—they were just what had been found to work (McClure, 1917).

It is interesting to hear the experiences of Dr. Huisheng Xie (personal communication), the noted Chinese herbalist, after he came to the United States. In China, veterinarians received the lowest-grade herbs for use with animals, while the high-quality herbs were sent to export and to human hospitals. In the United States, only high-quality human-grade herbs are used (those that were exported), in his experience, and the doses required to get results dropped dramatically, to a level that is only a few times higher than the human dose.

Personal clinical experience has shown that a good rule of thumb for veterinarians to follow is to treat horses with two to four times the human dose of any given herb. Some modern herbal literature often uses a “handful” of leafy herbs as one dose (deBairacli-Levy, 1976; Ferguson, 2002; Self, 1996). Measured a bit more exactly, this dose is approximately 30 grams or 1 ounce (Self, 1996).

A number of older methods of dosing are not used much today but certainly have potential. Dadd usually made mixtures of herbs in a liquid drench with something to make it palatable, such as caraway seeds or honey. McClure used flax oil, spirits of turpentine, warm ale, or aloes in a solution. He would fill an old champagne bottle and tip it up, giving the solution slowly without any force, to allow time for the horse to swallow. Perhaps in modern times, a plastic bottle could more safely be used. Dadd definitely had a gentle approach to the horse compared with others of his time.

Another common way to administer herbs at the turn of the last century was with the use of a ball, sometimes called a “Physic ball”. The ball was made with powdered herbs, linseed meal, treacle (pale cane syrup) or honey, and a bit of palm oil. These ingredients were mixed into a ball, with some being fairly hard, others slightly soft. Dadd believed this was bulky and difficult to give, that it required force to pull the tongue out and shove the bolus down the throat, and that it was slow to dissolve and deliver the active compound. Lawson and Clater used balls, frequently mixing in licorice powder to improve the consistency (Lawson, 1824; Clater, 1817).

FORMULA SELECTION

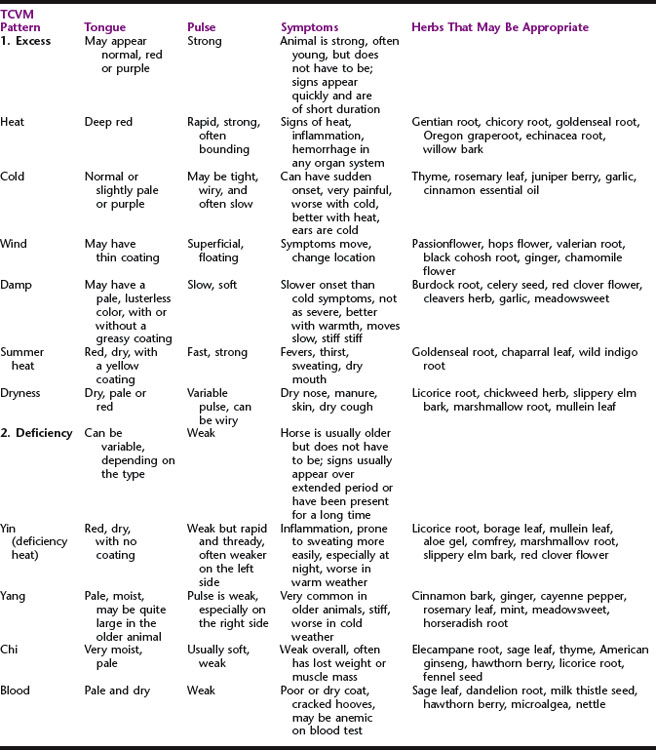

Lawson, a practitioner who was active in the early 1800s, described in detail pulses felt at the jaw line (Lawson, 1824). The normal pulse felt perfectly elastic, neither hard nor soft, but in fever, it was increased. With fever, the pulse felt hard and rigid, and it resisted pressure from the fingers. He recommended bleeding until the pulse felt softer. The Chinese also used bleeding techniques when monitoring results by checking the pulse. Although this text does not discuss Chinese medicine, it is interesting to note that some early herbalists in this country used the same type of information (Table 21-4).

Energetic or Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (TCVM) Signs

The tongue and pulse are used by TCVM practitioners to detect internal imbalances. These characteristics can help the practitioner determine which type of herb or formula to select. Although they are not easy techniques to learn, tongue and pulse diagnosis can be very useful tools. Tongue color is examined in natural daylight. The pulse is felt at the base of the neck over the jugular vein. The reader is referred to Chinese medical texts and training for more detailed information (Xie, 2002). The basic presentations are listed here, along with examples of herbs that fit these patterns (Holmes, 1997). The first priority when examining a case is to decide whether the animal has an excess or deficient condition; then, the practitioner must decide which type of excess or deficiency is present.

Once the diagnosis has been made, an individual herb or formula can be selected. Experienced herbalists can customize a single herb or a formula for individual cases. For many veterinarians, a prepared formula will be the preferred choice. The choice of which company’s formulas to use should depend on the quality of the company’s herbalist and the herbs themselves (see above, and Chapter 8 for more information). A formula can be selected on the basis of the clinical picture and fed for at least a month (about 2 weeks if the formula is in tincture form) before a reevaluation is undertaken to determine whether there has been a response.

PRESCRIBING CONSIDERATIONS

One of the most likely reasons for a well-selected formula or herb not to work is that the digestive tract is functioning poorly. Horses are often fed large quantities of antibiotics for every cut, scrape, nasal discharge, and bug bite. They are also commonly fed extremely large quantities of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, the most common of which—phenylbutazone—leads to significantly increased permeability of the intestinal tract wall (McAllister, 1993). Antibiotics change the bacterial flora, so digestion may not be as complete as in a horse whose beneficial bacteria and protozoa are intact (Rolfe, 1984; Zinn, 1993). Because bacteria and protozoa are important for cellulose or plant wall digestion, an unhealthy digestive tract may not process herbs optimally.

Common Causes of Gastrointestinal Tract Dysfunction

FORMULAS FOR COMMON EQUINE CONDITIONS

In this section, treatments for some of the most common equine-specific conditions are presented from historical and modern perspectives. Conditions present in all species such as liver disease are discussed elsewhere in this text. Formulas can apply to the equine if the doses are adjusted. The number of commercial formulas available to treat equine disease is large and formulas given here are examples to build from, rather than to copy without thought. It would appear that herbalists at the turn of the century were as discouraged with much of the conventional medicine practiced then as herbalists are in the present time. Dadd and McClure were the main references for this section, unless otherwise noted (Dadd, 1854; McClure, 1917).

General Health and Tonics

Historically, the following tonic was used for horses that were thin or needed to restore their health: 1.5 ounces each of powdered gentian, sassafras, sulphur, ginger, and fine salt, with 1 pound oatmeal, mixed and divided into 12 parts, fed twice a day until it was gone (Dadd, 1854). An alterative formula for restoring secretions and excretions after an illness consisted of equal parts of powdered sulphur, bloodroot, sassafras, cream of tartar (by-product of grape fermentation, the major component of baking powder), and skunk cabbage. One-half ounce was given twice a day mixed in food. Another variation recommended by Dadd to restore health in thin, “hide-bound” (dry coat, dehydrated) horses was made up of the following: 3 ounces each sassafras bark, sulphur, and salt, with 2 ounces bloodroot and balmony and 1 pound oatmeal, divided into 12 parts, given daily.

Another tonic, taken from McClure, that is used to revive horses after an illness included ginger or gentian combined with sulphate of copper (an ingredient then considered a powerful tonic for the whole body). Several other tonic formulas to be given after illnesses included (1) 1 ounce Peruvian bark, ½ ounce dry opium, 20 drops oil of caraway, and enough treacle to form a ball; (2) 1 drachm (1.8 g) gentian, ½ drachm (0.9 g) ginger, 1 drachm (1.8 g) cascarilla, with treacle and linseed meal to form a ball; and (3) 2 drachms (3.5 g) myrrh, 1 drachm (1.8 g) mustard flour, 5 grams cantharides, and 4 drachms (7.1 g) chamomile, mixed with Venice turpentine to make up the liquid part of the ball. Another tonic for lean, unhealthy, and hidebound horses is taken from Lawson (Lawson, 1824): caraway seeds 1 ounce, 0.5 ounces each of gentian root, zeodary root, fenugreek seeds, and mithridate, mixed as a powder, then given with 1.5 pints of ale in the morning every 2 to 3 days (formulas must not be boiled with seeds).

Even Youatt, who was not an herbalist but a conventional practitioner of the time, claimed to use some herbs in his treatments (Youatt, 1843). He most often practiced the regular medicine of the day with mercury and arsenic. However, one of his herbal tonics was a combination of ginger and gentian beaten together and made into a ball with treacle; another consisted of 4 drachms (7.1 g) gentian, 2 drachms (3.5 g) chamomile, 1 drachm (1.8 g) carbonate of iron (nonirritating, tasteless preparation of iron), and 1 drachm (1.8 g) ginger made into a ball.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree