Section 2 Patient Evaluation and Organ System Examination

Patient evaluation

Owner assessment of pet health: the beetts test

Clinician initial assessment: the problem list

1. The clinical history: Any abnormality described by the owner (whether or not the owner’s interpretation is correct) is a problem.

2. The physical examination: Any abnormality discovered during the physical examination is a problem (see Organ System Examination).

3. Any imaging (radiographic or ultrasound) or laboratory abnormalities are considered to be problems.

Physical Examination

Vital Signs

Temperature, pulse, respiration, and weight are the most fundamental health parameters evaluated when examining the patient. Capillary refill time (CRT) is commonly recorded (normal: < 2 seconds) but is a relatively poor test of peripheral vascular perfusion. Blood pressure (see Section 4) is more sensitive but requires some operator experience to obtain reliable readings and multiple measurements in the individual patient to obtain a reasonable value. Although weight is not strictly a “vital” sign, all patients should be weighed at every visit.

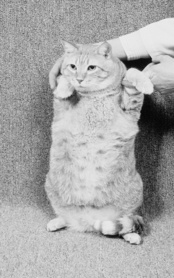

Conformation and Body Condition Score

The Laboratory Database

Clinical evaluation of the sick patient entails obtaining a laboratory profile to assess and characterize biochemical and hematologic abnormalities. Laboratory test abnormalities are a critical component of the diagnostic evaluation and are necessarily included, individually, on the patient’s problem list. In companion animal practice, performing a laboratory profile meets the standard of care accepted in veterinary medicine. Although the specific test methods used and analytes assayed will vary from practice to practice, the laboratory database for any ill dog or cat should include most or all of the tests listed in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1 Components of the Minimum Laboratory Database (MDB) for Dogs and Cats

| Canine | Feline | |

|---|---|---|

| Hematology | Complete blood count (CBC) includes the following: | Complete blood count (CBC) includes the following: |

| Note: Some laboratories will also provide values for the RBC indices: MCV, MCH, and MCHC. | Note: Some laboratories will also provide values for the RBC indices: MCV, MCH, and MCHC. | |

| Biochemistry | Individual analytes included on biochemistry panels will vary among laboratories. (See Section 5 for a comprehensive review of the various analytes that are likely to be included.) | Individual analytes included on biochemistry panels will vary among laboratories. (See Section 5 for a comprehensive review of the various analytes that are likely to be included.) |

| Urinalysis | Includes the following: | Includes the following: |

| Parasites | Fecal flotation for intestinal parasites Heartworm antigen test | Fecal flotation for intestinal parasites |

| Other | Feline leukemia virus (antigen) test and feline immunodeficiency virus (antibody) test |

MCH, mean corpuscular (cell) hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular (cell) hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean cell volume; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

The availability of numerous supplemental laboratory tests (see Section 5) dictates careful assessment of the initial laboratory database described. The decision to perform additional or specialized laboratory tests is based on the clinician’s interpretation of initial test results and physical examination findings.

Imaging and Special Diagnostics

The results of any abnormal findings observed with conventional radiography, ultrasound examination, or echocardiography or as a result of performing special diagnostic procedures are defined and included individually on the patient’s problem list. Routine, special, and invasive diagnostic procedures are described in Section 4.

The medical record

Medical record content

Inpatient Medical Record

1. Patient identification data, including patient’s name, date of birth, breed, gender, current owner’s address, and medical record identifier or number

2. Admission and discharge date (and time)

3. Existing diagnosis(es) and date

4. Medical history, to include the following:

5. Statement on the conclusions or impressions drawn from the admission history and physical examination

6. Statement on the course of action planned for this episode of care and its periodic review, as appropriate

7. Diagnostic tests ordered or recommended and therapeutic orders

8. Evidence of informed consent, as appropriate

9. Clinical observations and progress notes, including the results of therapy and the patient’s response to treatment

10. Information on every medication ordered or prescribed and administered, to include dosage and any adverse drug reaction

11. Reports of all operative and other invasive procedures performed

12. Reports of any diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and test results

14. Recommended: Conclusions at termination of hospitalization to include a discharge summary, condition at discharge, disposition of care, and provisions for follow-up care

Outpatient Medical Record

1. Patient identification data, including patient’s name, date of birth, breed, gender, current owner’s address, and medical record identifier or number

2. Admission and discharge date and time

3. Relevant history of the illness or injury and physical findings

4. Diagnostic and therapeutic orders

5. Clinical observations, including results of treatment

6. Evidence of informed consent, as appropriate

7. Report of procedures, tests, and results

9. Patient disposition and pertinent instructions given to owner for follow-up care

Emergency Patient Medical Record

1. Patient identification data, including patient’s name, date of birth, breed, gender, current owner’s address, and medical record identifier or number

2. Admission and discharge date and time

3. Emergency care provided to the patient by the owner or other veterinarian before arrival, if any

4. History of disease or injury

6. Results of diagnostic tests, if applicable

9. Conclusions at the termination of treatment are documented, to include the following:

10. Notation when owner refused medical care

11. Patient transfer information provided to other facilities (e.g., an after-hours emergency practice), when applicable, to include the following:

The organ system examination

The alimentary tract

The Dental Examination

Normal Dentition: Canine

Formula for deciduous teeth: 2 (Di3/3 Dc1/1 Dm3/3) = 28 (total)

Formula for permanent teeth: 2 (I3/3 C1/1 P4/4 M2/3) = 42 (total)

Canine eruption dates are shown in Table 2-2.

Table 2-2 Eruption Dates of Deciduous and Permanent Teeth—Canine

| Age at Eruption | ||

|---|---|---|

| Teeth | Deciduous (Weeks of Age) | Permanent (Months of Age) |

| Incisor 1 | 4-5 | 4-5 |

| Incisor 2 | 4-5 | 4-5 |

| Incisor 3 | 5-6 | 4-5 |

| Canine | 3-4 | 5-6 |

| Premolar 1 | — | 4-5 |

| Premolar 2 | — | 5-6 |

| Premolar 3 | — | 5-6 |

| Premolar 4 | — | 5-6 |

| Molar 1 | 4-6 | 4-5 |

| Molar 2 | 4-6 | 5-6 |

| Molar 3 | 6-8 | 6-7 |

Normal Dentition: Feline

Formula for deciduous teeth: 2 (Di3/3 Dc1/1 Dm3/2) = 26 (total)

Formula for permanent teeth: 2 (I3/3 C1/1 PM3/2 M1/1) = 30 (total)

Feline eruption dates are shown in Table 2-3.

Table 2-3 Eruption Dates of Deciduous and Permanent Teeth—Feline

| Age at Eruption | ||

|---|---|---|

| Teeth | Deciduous (Weeks of Age) | Permanent (Months of Age) |

| Incisor 1 | 2-3 | 3½-4 |

| Incisor 2 | 2-4 | 3½-4 |

| Incisor 3 | 3-4 | 4-4½ |

| Canine | — | 5 |

| Premolar 1 | — | — |

| Premolar 2 | — | 4½-5* |

| Premolar 3 | — | 5-6 |

| Premolar 4 | — | 5-6 |

| Molar 1 | — | 4-5 |

| Molar 2 | 4-5* | — |

| Molar 3 | 4-6 | — |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree