CHAPTER 19 Approaches in Veterinary Herbal Medicine Prescribing

There is no one correct system of prescribing. Ten herbalists can prescribe different formulas and still achieve success in treating a patient.

HERBAL PRESCRIBING DIFFERS FROM ORTHODOX MEDICINE

When predisposing or perpetuating factors cannot be changed, herbal medicine may also be effective in the treatment of patients with chronic disease as an alternative or complementary medicine to long-term drug treatment. Herbs can be used when a conventional drug may be undesirable, to lower the dose of conventional drugs, or to reduce the adverse effects caused by conventional drugs.

TRADITIONAL APPROACHES TO PRESCRIBING

Traditional Diagnosis

Elements of the human environment were seen as a reflection of the underlying belief that the microcosm mirrors the macrocosm—the interrelatedness of all things (Moore). For example, the impact of the “elements” on the patient was considered. In contemporary veterinary herbal medicine, it is no surprise that in summer, when the weather is hot and humid, dogs are prone to “hot spots,” and in winter, dogs suffer more Bi syndrome, or an invasion of “cold” into their arthritic joints. Energetics diagnosis was both literal and metaphoric and was useful in prescribing. Heat experienced by the patient, or “hot” signs, would be balanced by “cooling” herbs. (See Chapter 13 on Chinese medicine for a more detailed explanation of the traditional Chinese approach to energetics of herbal medicine.

Traditional Concepts

The “Vital” Force

Vitalism has provided the foundation for medical thinking since the times of Hippocrates and Galen. The premise of Vitalism considers that living processes are animated by the Vital Force, which starts flowing at the moment of conception and ceases with death. This flow of vital energy in the body nourishes, heals, develops, and sustains the body. The flow of Vital Force is linked with the emotional experience of the being, wherein emotions have a direct effect on the body’s physiologic function and thoughts affect emotion. Thus, Vitalism embraces the interrelationships of mental, emotional, and physical experience; and holistic thinking about the human (and animal) body has served as the basis for almost all traditional systems of medicine (Holmes 1997).

Traditional Chinese medicine

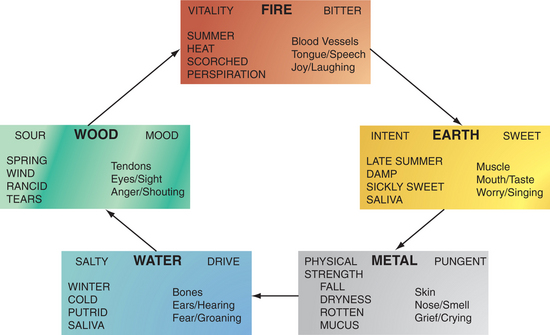

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is based on the theories of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, which have arisen from ancient Chinese observations of nature’s cycles and changes (Figure 19-1). These theories held that wood, fire, earth, metal, and water are the basic substances constituting the material world. These five basic substances were considered an indispensable part of daily life. Each of these elements represents a category of related functions (concordances) and qualities pertaining to direction, season, climatic conditions, color, taste, smell, yin and yang organs, body opening, body tissue, emotion, and human sound.

Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine Prescribing:

The Minister herb is bai zhu (white atractylodes). It tonifies Spleen Qi and resolves Damp. The assistant herb is fu ling (poria); it helps to drain Damp and tonify the Spleen, helps resolve phlegm, and calms the Heart and the Shen. The Guide herb is Gan Cao (licorice), which harmonizes the herbal formula (reducing potential adverse effects) and guides the formula through all 12 main channels; it also tonifies the Spleen, Heart Qi, and Lung Qi and moderates the actions of the other herbs.

| Withania somnifera | 40% |

| Chamomilla recutita | 30% |

| Althaea officinalis | 20% |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | 10% |

Ayurveda:

Ayurveda identifies three basic types of energy (called doshas) that are present in everybody and everything; these are Vata, Pitta, and Kapha. These doshas are in turn related to the elements of Air, Fire, Water, and Earth (Vata-Air, Pitta-Fire and Water, Kapha-Water and Earth). All people and animals have Vata, Pitta, and Kapha, but one is usually primary, one secondary, and the third least prominent. Vata is the energy of movement, Pitta the energy of digestion or metabolism, and Kapha the energy of lubrication and structure. The cause of disease in Ayurveda is viewed as the lack of proper cellular function because of an excess or deficiency of Vata, Pitta, or Kapha, or the presence of toxins. As with the humoral theory, balance and health are maintained through a variety of lifestyle, diet, and medicinal interventions. (See Chapter 6 for more information.)

Humoral theory

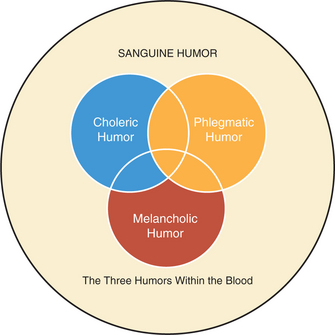

The four humors are perceived within the blood through each of the four Elements in turn (Figure 19-2):

Samuel Thomson (1769–1843) developed a system of practice that recalled elements of this theory. He thought that all diseases are brought about by a decrease or change in vital fluids—the humors—“either by taking cold or the loss of animal warmth.” He saw health as a balance within the body of four elements—earth, air, fire, and water. Accumulated wastes led to obstruction, lessening heat in the body and resulting in disease. With diffusion of heat throughout the body, the obstruction could be removed. Thomson saw fever and sweating as natural responses of the body designed to eliminate wastes via the skin. It was therefore logical to conclude that diaphoretics such as Capsicum would aid sweating during fever, thus assisting the innate healing power of the body (Griggs 1997).

Humor and Temperament:

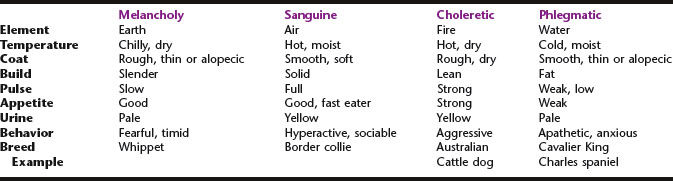

Each humor has its own temperament in terms of hot, cold, wet, and dry and is traditionally ruled by different planets. The humors can be explained from both symbolic and biochemical viewpoints, and they can be used to parallel biochemical medicine. The symbolism of the Elements also helps to reveal the nature of the humors (Table 19-1).

The temperament was often used as a starting point for evaluating health and disease and would serve as the basis of herbal prescribing. To determine temperament, herbalists would assess the color and shape of the body, as well as habits, personality, temperature, pulse, colors, odors, and consistency of excretions. For a representation of this in veterinary terms, see Table 19-1.

Physiomedicalism

Modern physiomedical prescribing

Physiomedical concepts have evolved into a step-by-step process for developing a formula. This method has been described by Bone and allows the herbalist to set treatment goals, prescribe efficiently, and monitor the progress of patients (Mills 2000, Bone, 1994, 1996). It is especially useful in treating patients who present with a wide range of clinical signs and symptoms. The basic principle is to write balanced prescriptions by setting short-term and long-term goals that are appropriate for the individual patient.

The steps involved in physiomedical prescribing are described in the following sections.

Physiologic Enhancement:

Body energy is also optimized, which can be accomplished through the use of tonics and adaptogens, which improve energy level and enhance the ability to cope with stress, thereby helping to conserve vitality. This may also require the enhancement of specific organs like the kidneys or adrenals.

Treat the Perceived Causes:

A formula for this patient might be as follows:

| Eleutherococcus senticosis | 40% |

| Echinacea angustifolia | 30% |

| Sambucus nigra | 20% |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | 10% |

Match the Treatment to the Patient:

The herbal formula administered should be matched energetically and constitutionally to the patient (Table 19-2). “Warming” herbs are thought to aggravate “hot” patients, and “cooling” herbs may aggravate cold patients. Thus, if a cooling herb is indicated for a cold patient, warming herbs should be added to compensate for these potentially adverse energetic effects. This is one of the reasons why tonics (which are usually warming) theoretically should not be used in patients with acute infection.

TABLE 19-2 Determining the Energetics of the Patient

| Heat signs | Cold signs |

|---|---|

| Caused by dehydration, diet, extreme behaviors, hot weather, failure to eliminate toxins (constipation) | Result from lack of heat or vitality; exposure to cold weather, cold foods, some chronic illness |

| Red, sometimes dry, tongue | Pale tongue |

| Panting | Poor circulation |

| Red eyes | Diminished mental ability |

| Upper body affected (heat rises) | Catarrhal respiratory tract |

| Red, inflamed skin | Chills, shivering |

| Fever | White or clear discharge |

| Inflamed mucous membrane | Frequent urination |

| Dry cough | Large volumes of pale urine passed |

| Bleeding | Limbs often affected (colder parts of body) |

| Irritation | Slow, deep pulse |

| Dry eyes | Dislike of cold, tendency to seek heat |

| Pain | Aggravated by cold weather |

| Yellow discharge | Fatigue |

| Scant, dark urine; strong odor | Fixed pain, stiff joints |

| Thirst | Poor digestion, bloating |

| Worsening of symptoms in hot weather | Diminished appetite |

| Moist signs | Dry signs |

|---|---|

| (= Dampness of traditional Chinese medicine) | Windy weather, dry foods, lack of fluids, extreme emotions |

| Overeating, especially of certain types of food; humid weather, damp environment, sedentary lifestyle, emotional turmoil, inactivity, poor vitality | Dry skin, cracked skin on nose |

| Dry nails | |

| Dry and red eyes (heat) | |

| Greasiness | Inflamed, dry, itchy skin or mucous membranes (dry heat) |

| Ulcers, abscesses, blisters | Wheezing, shortness of breath, dry cough |

| Thick mucus | Dry and red tongue (heat) or pale tongue (cold) |

| Clear, white mucus (cold) | Pulse rapid (heat), slow (cold), or indistinct |

| Offensive discharge (heat) | Dislikes wind, worse in autumn |

| Moisture settling in lower part of body (cold) | Thirsty |

| Cloudy urine, strong smell (heat) | Muscle wasting and weakness |

| Slippery, rapid pulse (heat) or slow and deep pulse (cold) | Allergic conditions |

| Wet tongue | Restlessness associated with heat |

| Dislike of cold, wet places or weather | Dry stools |

| Sore joints, stiffness worse with rest, improvement with movement | Poor resistance to infection of skin, mucous membranes, and respiratory tract |

| Diminished appetite, poor digestion (especially fatty food) (heat) | Insatiable thirst; likes swimming, water |

| Copious diarrhea with mucus (cold) or with offensive odor (heat) | |

| Poor resistance to infection | |

| Constipated or with edema | |

| Diseases of liver, gallbladder often associated with moist hot disorders | |

| Phlegmatic individual (cold and moist) more dull | |

| Sanguine (hot and moist) less forceful |

Modified from Trickey R. The origins of disharmony. Modern Phytotherapist 1998;4:19–127.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree