CHAPTER 16 Commercial Production of Organic Herbs for Veterinary Medicine

The resurgent interest in herbal medicine in the Western world can be characterized as an herbal renaissance. Over the past 20 years, the increasing depth and breadth of rekindled interest in traditional herbal medicine has placed the market near full circle. Although practitioners are strongly dependent on pharmaceutical drugs, a move is taking place toward the herbal remedies that are derived from plants that grow in meadow, plain, field, lot, roadsides, and household backyards. These plants offer efficacy, minimal adverse effects, and wide availability, and their activities are increasingly understood with scientific investigation. Advocates believe that not only is botanical medicine an important part of the future of veterinary medicine, but it is fast becoming the “leading edge” of veterinary medicine.

WHAT IS A SUSTAINABLE HERB FARM?

Following are some factors that growers should consider when they choose crops to grow:

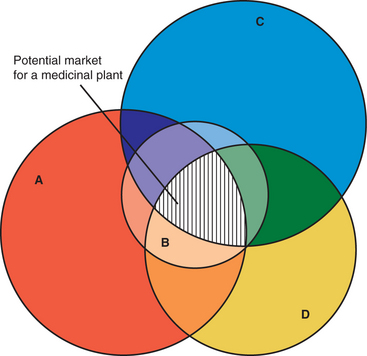

The decision-making process starts here. The considerations listed above are represented as circles in Figure 16-1. In the area where there exists a mutually inclusive overlap of all four circles, a potential market awaits exploration. The overlap area set of conditions is ideal: a potential herbal remedy exists for an important clinical condition, conventional treatment is not satisfactory or problematic, and the herb can be grown on the land that is available. When the market is still small, these conditions allow for its growth.

KEY ISSUES FOR HERB GROWERS

Growing for quality requires the following:

CROPPING MEDICINAL BOTANICALS

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree