14 Ophthalmologic Disorders

Case 14-1 Foal with Entropion and Cataract

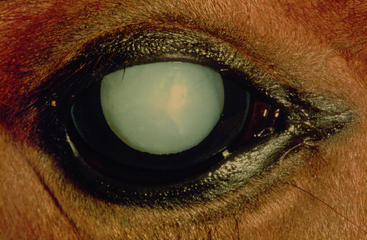

’04 FortyLashes, a five-day-old Paint foal colt, presented for evaluation of ocular discomfort of the right eye (OD), evident as tearing and squinting that developed two days after birth (Figure 14-1). The referring veterinarian had made a diagnosis of lower-lid entropion OD. Upon closer examination of the eyes, a lens opacity in the left eye (OS) was also evident. The otherwise healthy foal was referred to the hospital for cataract evaluation and further management of the eyelid condition after treatment with an ophthalmic broad-spectrum antibiotic three times daily had failed to improve the clinical signs of OD.

Ocular disorders in neonates have been reported to represent 5% of all equine ocular disorders and may be categorized as congenital, inherited, or acquired.1–4 While congenital disorders (present at the time of birth) may be genetically based, they also may develop secondary to various insults in utero, including infection, nutritional deficiencies or excesses, drugs, toxins, trauma, ionizing radiation, and other unknown or idiopathic factors. Ocular examination of the equine neonate should be performed in the immediate newborn period and at any follow-up visits as part of the routine physical exam. This approach ensures early detection and, if treatable, proper management of ocular conditions that may otherwise result in lifelong visual impairment. It will also help to optimize breeding programs since patients affected by inherited ocular disease may be excluded from breeding, therefore limiting economic losses.

THE NORMAL EQUINE NEONATAL EYE

Foals are born with their eyes open. The pupils are initially round to oval in shape and become more horizontal at three to five days postpartum with a lighter-colored iris than adult horses. A reliable menace response is absent until two weeks of age and can therefore not be used as assessment of vision in the immediate postnatal period.5 While the pupillary light reflex (PLR) is present at the time of birth, it may be sluggish in a highly excited foal due to a high sympathetic tone. Therefore, optimal testing for PLRs should take place in a quiet and relaxed environment; a bright focal illuminator (e.g. Finoff illuminator) should be used to evaluate for PLRs in bright and dim light.

Neonatal foals also show a lower tear secretion than adults, which may be accompanied by decreased corneal sensitivity and lagophthalmos in sick foals.6–8 A mild ventro-medial deviation of the eyes can be seen in foals less than one month old. Iris color in most foals is brown, but variations known as “Heterochromia iridis” may be seen in color-dilute foals or those carrying color-dilute genes (e.g., Palomino, Appaloosa, Paint).4 Heterochromia iridis refers to a lack of iridal stromal pigment and clinically manifests itself as a combination of white and blue iris color with brown corpora nigra (“wall eye”) or white iris with brown corpora nigra (“china eye”).

Lens suture lines (“Y-sutures”) are commonly observed in newborn foals and are, unlike cataracts, insignificant without impact on vision.1,2 Persistent hyaloid artery remnants are another frequent finding in equine neonates, especially in premature foals.4,9 They result from a failure of part or all of the hyaloid artery to regress and can be appreciated as a fine gray-white linear opacity (in some cases containing blood) spanning from the optic disc to the posterior lens capsule. Regression of these remnants usually occurs at three to four months of age. Attachment of these remnants to the posterior lens capsule may result in focal posterior capsular and subcapsular cataracts that are nonprogressive and often not associated with visual impairment.

CONGENITAL OPHTHALMIC ABNORMALITIES

Inversion of the upper and especially lower eyelids is the most common congenital lid abnormality in foals and may occur on a primary basis or secondary to microphthalmia or lid trauma. Sick or premature foals are predisposed to develop entropion due to dehydration, a negative energy balance, or malnutrition, which all lead to mild enophthalmos and secondary inversion of the lids due to lack of support by the globe.1,10,11

Reports of delayed or incomplete lid opening in foals have been rare.12 Manual opening by applying minimal digital pressure and traction may be attempted, and if unsuccessful, surgical opening of the palpebral fissure should be performed under heavy sedation or general anesthesia.13 The eyelids are prepared using a diluted (1 : 10 to 1 : 50) povidone-iodine solution. After at least three scrubs, the area is rinsed with 0.9% sterile saline (alcohol should be avoided since it can severely damage corneal and conjunctival epithelia). The line of separation between the lids is cut using a scissor blade in sliding motion. Great care must be taken to avoid injury to the cornea. Postoperative treatment includes application of a topical broad-spectrum antibiotic four to six times daily for 10 days, or longer if necessary.

Congenital cataracts are commonly found in foals and have been reported to represent up to 35.3% of all congenital ocular lesions.1,3,4 Etiologic factors include heritability, uveitis, trauma, and nutritional deficiencies.1,11 Since genetic factors may contribute to congenital cataracts, affected patients should not be used for breeding.

Congenital cataracts may occur unilaterally or bilaterally and may range from smaller cataracts associated with persistent hyaloid artery remnants to nuclear to mature cataracts (Figure 14-2). Inherited cataracts have been reported in Belgians (associated with aniridia), Quarter Horses, Thoroughbreds, and Morgans.4,10,14,15 Congenital cataracts in Morgans appear as finely reticulated spherical nuclear translucencies that occur in a symmetrical fashion in both eyes without impairing sight. Cataracts and lens luxations are also frequent findings in Rocky Mountain Horses affected by anterior segment dysgenesis.16

Congenital lens subluxation or lens luxation can also be seen in the neonatal foal. It can occur as a single lesion or as part of multiple ocular anomalies and occurs secondary to a defect in lens zonule formation.17 Cardinal signs of lens dislocation include vitreous prolapse (white vitreal strands prolapsing through pupil), presence of an aphacic crescent (edge of displaced lens and ciliary zonules remnants appreciated through pupil), phacodonesis (lens tremor seen with globe movement), iridonesis (tremulousness of iris), and asymmetry in anterior chamber depth.

Microphthalmos is a congenitally small globe and can be found sporadically in all breeds of horses, especially Thoroughbreds.1,18 It can occur unilaterally or bilaterally with different degrees of severity. Pure microphthalmos describes a small but functional globe. Complicated microphthalmos refers to a small globe affected by other ocular defects, including cataracts and retinal dysplasia. Foals with only subtle microphthalmia usually suffer from marked visual impairment despite an only small reduction in globe size. The diagnosis can be facilitated by comparing the ocular dimensions of the affected eye with the contralateral eye (in case of unilateral disease) or with the eyes of healthy, age-matched control foals. Caliper measurements of the dorsoventral and horizontal corneal diameters are useful. Globe diameter can be determined via ocular ultrasound (B-scan). The degree of third-eyelid protrusion is directly related to the degree of microphthalmos.

In severely affected patients, no lid opening may be found and anophthalmos may be suspected. However, closer inspection of the eyes will show rudimentary ocular tissue (Figure 14-3). In these patients, enucleation is strongly recommended to prevent future ocular complications such as chronic conjunctivitis and corneal irritation from entropion. The enucleation procedure should include placement of an orbital implant (especially in young patients) to prevent malformation of the growing skull, since globe development dictates development of the bony orbit. If a foal is suffering from complete blindness due to bilateral severe microphthalmia, euthanasia should be considered for humane reasons.

Multiple ocular anomalies have been seen in the neonatal foal. These congenital abnormalities may include corneal lesions, microcornea, megalocornea, dermoids, persistent papillary membranes, aniridia, iridal hypoplasia, anterior segment dysgenesis, enlarged corpora nigra, iridal colobomata, lens luxation, cataracts, retinal dysplasia, and retinal detachment.1,3,4,15,16,19,20 Any breed may be affected with lesions occurring in either one or both eyes. Affected eyes are often blind in cases of multiple anomalies and should be enucleated in cases of unilateral disease.

Congenital buphthalmia (globe enlargement) is often associated with multiple ocular abnormalities and chronic glaucoma.21,22 Treatment consists of enucleation for pain relief and prevention of complications such as exposure keratitis from subsequent inability to fully close the eyelids over the enlarged globe.

Congenital strabismus (hyperopia) and dorsomedial strabismus, a deviation of the eye from its physiological position, have been reported in Appaloosa foals and may be associated in this breed with congenital stationary night blindness.23,24 This strabismus becomes more evident when the foal tries to focus on an object or when it is placed in an unfamiliar environment. Corrective surgery consisting of ocular rectus muscle transposition may result in improvement of clinical vision and behavior. While congenital strabismus is rarely found in foals, it has been reported in mules with an incidence of 1 in 200.25

Glaucoma refers to an increase in intraocular pressure that is no longer compatible with normal physiologic function of the eye. Congenital glaucoma in foals of various breeds has been described and was attributable in these patients to abnormal differentiation of the iridocorneal angle (goniodysgenesis).4,22,26,27 While glaucoma in adult equine patients is often secondary to underlying uveitis, it has not been reported in equine neonates. Accurate diagnosis of glaucoma requires applanation tonometry using a tonopen. The mean intraocular pressure in horses has been reported to range from 16.5 to 32.5 mm Hg with a mean of 24.5 mm Hg. A thorough ocular examination should rule out presence of other ocular abnormalities before medical or surgical treatment recommendations are made. Clinical signs depend upon the stage of glaucoma and include moderate buphthalmia, conjunctival injection unresponsive mydriasis, iris atrophy, corneal edema and/or striae, lens luxation or subluxation, retinal atrophy, optic nerve cupping, and blindness.

Congenital retinal diseases include retinal dysplasia, chorioretinitis, optic nerve hypoplasia, optic nerve colobomas, and night blindness. Retinal dysplasia is anomalous retinal differentiation with proliferation of one or more of its constituent elements. Histologic characteristics are folding of the sensory retina and formation of retinal “rosettes” that are composed of one or more layers of neuroblasts surrounding a central lumen. The condition is congenital and suspected secondary to infectious, traumatic, and toxic insults occurring during fetal development.1,4,28 It is usually bilateral and nonprogressive, and vision depends upon severity of the lesion and presence of other ocular anomalies. Ophthalmoscopic findings include single or multiple focal dots or linear streaks as well as geographic lesions.

Fetal exposure during late gestation to various infectious agents (especially in mares with active respiratory disease) may result in congenital chorioretinitis.29 Clinically, gray or grayish-white indistinct circular lesion in the non-tapetal fundus indicate active chorioretinitis. Healed lesions appear as chorioretinal scars or “bullet-hole” lesions in the non-tapetum. They are characterized as sharply demarcated circular depigmented lesion with a darkly pigmented center. Unless the scars are numerous (>20) or the horse appears to have visual difficulties, they are considered insignificant.10

Optic nerve hypoplasia is a congenital condition referring to a smaller than normal optic disc due to a failure of retinal ganglion cells to develop. Fundic examination shows a pale, small optic disc and either attenuated or completely absent retinal vasculature. One or both eyes may be affected, and other ocular abnormalities may be present.10 Affected patients show abnormal PLRs but may still have some vision, depending upon the severity of the condition.

Optic nerve colobomas are congenital malformations of the optic nerve head and peripapillary area. They appear as excavations of the optic disc, and their size is directly related to the severity of visual impairment.30

Equine night blindness (nyctalopia) is a nonprogressive congenital condition that has been described in Appaloosas, Quarter horses, Thoroughbreds, Paso Finos, and Standardbreds.10,24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree