12 Umbilical and Urinary Disorders

Case 12-1 Umbilical Infection/Patent Urachus

Mutiny, a 59 kg Hanoverian colt, presented with his dam at nine days of age for evaluation of mild diarrhea and mild lethargy (Figure 12-1). On physical examination, the foal was found to be bright and alert, and auscultation of the thorax and abdomen revealed no murmurs, arrhythmias, or adventitial lung sounds. The heart rate and respiratory rates were normal, but the foal had a rectal temperature of 103.2° F. His mucous membranes were moist but slightly injected, and the capillary refill time was less than two seconds. The foal’s tail was wet, and the hindquarters were stained with watery manure. No heat or effusion was noted in any palpable joint, but the umbilical stump was wet and subjectively thickened.

HISTORY AND PRESENTATION

There is no published data that describes the prevalence of umbilical disease in foals; however, in neonates with failure of passive transfer or frank infection, omphalitis is a common comorbidity. The external signs of omphalitis include a thickened umbilical stump, perinavel edema, purulent drainage, and/or patent urachus (Figure 12-2). However, umbilical infection is frequently not apparent on physical examination, but only found via additional imaging when a clinical suspicion arises. Studies performed at two large referral centers found that approximately 50% of foals with evidence of ongoing infectious processes demonstrated ultrasonographic evidence of omphalitis or omphalophlebitis.1,2 An additional data set shows that 25% of septic foals had an umbilical infection, as did 50% of foals with septic arthritis or osteomyelitis.3 Because of this, the majority of foals treated within the hospital setting for omphalitis, omphalophlebitis, or urachitis were presented for other complaints. The important diagnosis of umbilical infection can often be delayed for days if foals at high risk are not evaluated in a timely manner.

Although umbilical infections have been documented in horses up to 16 months of age,4 more than 95% of cases are patients under eight weeks old and are associated with organisms that are common isolated in septicemic foals.5 The majority of equids mentioned in the literature are horse foals, although the condition has also been described in a Grevy’s zebra.6 The urachus is the most commonly involved structure,5,7,8 either patent, infected, or both. The vascular remnants are also commonly involved, showing extraluminal and intraluminal inflammation or abscessation, as well as involvement of the surrounding tissues.

PATHOGENESIS

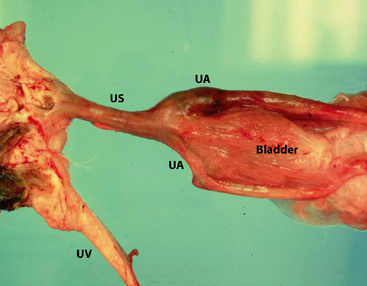

The umbilicus consists of the two umbilical arteries, the umbilical vein, and the urachus, all of which are enclosed in an umbilical sheath. In equine practice, commonly encountered disturbances of the umbilical remnant include omphalitis/omphalophlebitis, patent urachus, liver abscess, and umbilical hernia. There is no single pathogenesis for umbilical infection, but two studies look at risk factors.1,2 In both studies, criteria for sonographic evaluation of the umbilicus included grossly abnormal navel as described above, fever of unknown origin, leukopenia or leukocytosis, hyperfibrinogenemia, septic arthritis/osteomyelitis, body wall abscesses, positive blood culture, positive sepsis score, diarrhea, or pneumonia. These studies found that approximately half of the cases that fulfilled one or more of these criteria demonstrated umbilical pathology sonographically.

Postnatal treatment of the umbilicus has also been examined as a risk factor for omphalitis. Although dipping with 7% iodine or 1% povidone is traditional, a study comparing different bactericidal solutions found 0.5% chlorhexidine superior in decreasing the number of bacteria colonizing the stump, as well as minimizing chemical irritation of the tissues.9 In the case of 7% iodine, local tissue necrosis after treatment may be sufficient to provide an ideal culture medium for bacteria, actually increasing the likelihood of infection.

Much folklore also exists regarding the correct technique for severing the umbilical cord after birth. It is generally accepted that allowing the cord to break spontaneously when the mare rises is ideal, but contrary to popular belief, the cord can be severed immediately after parturition with no appreciable effect on the foal’s blood volume.10 The cord is narrowest at about 5 cm from the foal’s body wall, and it is at this area that the cord usually separates. The umbilical arteries retract approximately 6 cm within the abdominal cavity after rupture of the cord.11 If the cord must be manually separated, providing steady traction on the cord distal to the narrowing while supporting the foal’s abdomen at the umbilicus most closely resembles the natural event. Sharp transaction of the cord with clamp or ligature placement prevents retraction of the umbilical structures, and may explain why this procedure has been anecdotally associated with a greater number of complications.

Of the umbilical structures, the urachus is most commonly affected when omphalitis is diagnosed.7,8 Patent urachus is can be diagnosed by palpation (consistently wet umbilical remnant), visually (seeing “two streams” of urine during micturition from both the urethra and the umbilicus), or sonographically. Most of the literature suggests that patent urachus is usually associated with umbilical infection,7,12 although more recent data questions that assertion.5 It has also been hypothesized that excessive abdominal pressure from foal handling or lifting can contribute to the development of urachal patency.13 Congenital patent urachus, where urine is seen from the umbilicus from the first urination, is generally considered to respond well to conservative therapy such as cauterization. Patent urachus occurring after the first few days of life or secondary to umbilical infection is generally more refractory to medical management,8 although several authors describe considerable success with nonsurgical treatment.1

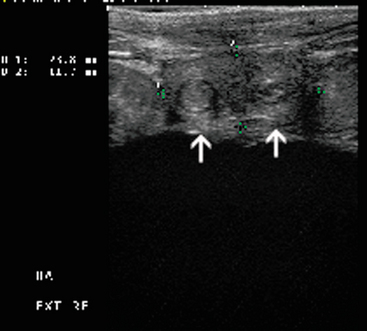

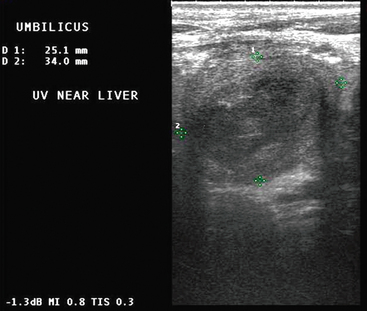

A diagnostic plan was devised for Mutiny. A complete blood count revealed a neutrophilic leukocytosis of 17,000 WBC/μl, and a fibrinogen of 500 mg/dl. The chemistry panel was unremarkable, and no evidence of dehydration or hypoperfusion was noted. Fecal samples were submitted for analysis for common foal diarrheic pathogens, and an ultrasound examination of the umbilical structures was performed. The umbilical stump was wider than normal (31 mm diameter) with significant edema, and the urachal wall was thickened with fluid and areas of gas shadowing within the lumen. The right umbilical artery was 25 mm in diameter, with a small amount (2 mm) of heterogeneous material in the lumen cranial to the bladder. The left umbilical artery and umbilical vein showed no abnormalities along its entire length.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

As most patients with omphalitis do not have umbilical abnormalities as a presenting complaint, the first aspect of diagnosis includes early clinical suspicion. An absence of palpable abnormalities in no way rules out omphalitis and should not be considered a reason to delay further diagnostic testing. Foals under eight weeks of age who have a history of failure of passive transfer or evidence of infectious or inflammatory disease should be considered for ultrasonographic screening. Evaluation of umbilical structures, both normal and abnormal, is well-described1,5,14,15 and within the capabilities of many equine veterinarians in general practice with some ultrasound experience and appropriate equipment.

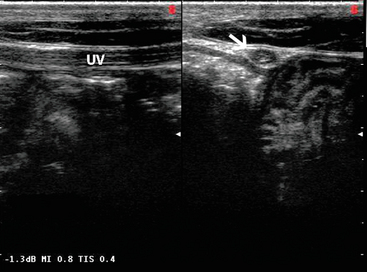

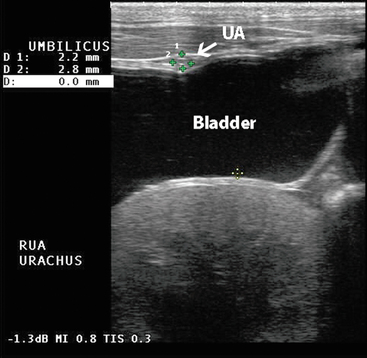

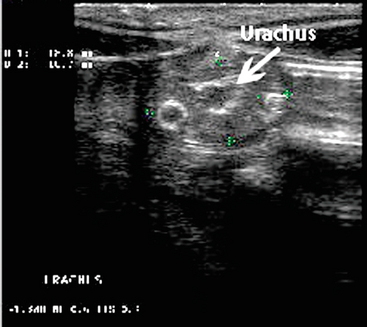

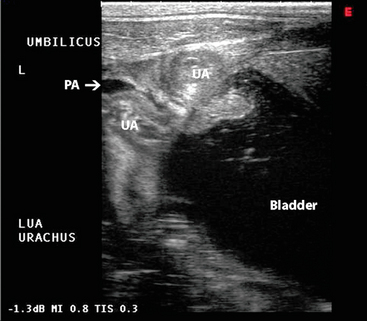

A 7.5 mHz transducer is used for the evaluation, and the foal can be evaluated in lateral recumbency or standing (Figure 12-3). A linear transrectal or tendon probe is acceptable. The abdomen is prepared by closely clipping a 4-cm strip along the ventral midline from the xiphoid to the umbilical stump, and a 5-by-5-cm area caudal to the stump (to the udder or prepuce), and cleaning the skin thoroughly. A full evaluation is made of each structure, in short- and long-axis, looking for enlargement from wall thickening or luminal dilation, as well as the presence of abscesses, gas shadows, or fluid accumulation. The umbilical stump is scanned first, and is usually less than 18 mm in diameter at 24 hours of age, decreasing to less than 15 mm at seven days of age (Figure 12-4, Table 12-1). The vein is then followed cranially and very superficially on midline until it terminates within the hepatic parenchyma, where it will eventually become the falciform ligament (Figure 12-5). It should be less than 10 mm in diameter at 24 hours of age, and reduced to less than 7 mm by seven days of age. There should be no areas of thickened wall, or heterogeneous fluid within the lumen (a small amount of anechoic fluid in the lumen for one to two weeks is usually normal), and the liver around the vein should be examined for the presence of abscesses. The arteries course caudally on either side of the urinary bladder, and mature into the round ligaments of the bladder. As the arteries are scanned caudally, deeper settings may need to be used. The arteries may contain echoic clot material, but it should not be inhomogeneous or contain gas shadows. Generally slightly larger than the umbilical vein, the arteries have a diameter of less than 13 mm at 24 hours of age, and less than 10 mm at seven days of age (Figure 12-6, Table 12-1).15

Fig. 12-4 Ultrasound image of the umbilical stump of a normal foal. Note the presence of the two arteries (a).

Courtesy of Dr. Kate Chope.

Table 12.1 Ultrasound Measurement of the Normal Umbilical Structure of the One-Day-Old and Seven-Day-Old Foal

| One Day of Age | Seven Days of Age | |

|---|---|---|

| Umbilical stump | <18mm | <15mm |

| Umbilical vein | <10mm | <7mm |

| Umbilical artery | <13mm | <10mm |

Ultrasonographic abnormalities of umbilical structures that can be evident in foals with omphalitis/omphalophlebitis include enlargement of the vessels beyond the normal limits, asymmetry of arteries with enlargement, abscessation of stump or single vessel, gas shadowing indicative of an anaerobic infection, edema of structures, and hematoma formation (Figures 12-7 and 12-8). The urachus is scanned both longitudinally and in cross-section, although patency is often most apparent in the former view. Longitudinally, a small “beak” at the bladder by the umbilical remnant can be normal in younger foals, but any evidence of urine extending through the urachus at the umbilical stump should be considered evidence of patency (Figure 12-9). The urachus is also evaluated for thickened walls and gas, and when imaged with the arteries, is found to have a composite diameter of less than 25 mm. The bladder should also be evaluated, and found to be oval with anechoic or slightly speckled urine.

Fig. 12-8 Ultrasound image of an enlarged umbilical vein prior to entering the liver.

Image courtesy of Dr. Kate Chope.

TREATMENT

Traditional treatment for infection of the umbilical structures has included complete resection of the umbilical remnant by celiotomy.16 More recently, Fischer described a laparoscopic-assisted resection of umbilical structures to minimize soft-tissue swelling, edema, and associated morbidity and discomfort.17 Large venous abscesses are sometimes too large for full excision, but have been treated successfully with a one-stage marsupialization procedure.18 This condition may carry a worse long-term prognosis due to an apparently greater risk for adhesions.5 In recent years, there has been increasing interest in treating umbilical infections medically. In one study of approximately 75 foals with umbilical abnormalities, 75% were treated with medical management alone. After three to seven days, the majority of foals showed ultrasonographic improvement, although in some cases an alteration in antibiotic change was necessary before improvement was noted. The majority of foals were treated for two or more weeks before full resolution was achieved.1

Foals that should be referred to surgery include those with substantial abscessation or venous involvement that extends as far as the liver.1 Other suggested criteria for surgical treatment include extremely large umbilical structures, the presence of multiple infected structures (especially infected joints, which suggests the presence of a septic focus), or ultrasonographic evidence of purulent material.5 Patients that are potentially going to receive surgical resection should receive one to four days of parenteral antibiotics prior to celiotomy in an attempt to minimize abdominal contamination. Considerable variation exists among centers in the proportion of cases that are treated surgically versus medically. Although one might assume that medical therapy would be a good option for owners with financial constraints, this is not necessarily the case. In one hospital, otherwise healthy foals treated with antibiotics only for umbilical remnant infections did not show a significant decrease in cost when compared to surgery.2

Antibiotic therapy for omphalitis generally precedes the acquisition of culture and sensitivity results, and selection is therefore empirical. Mixed infections are likely, and common isolates include Gram-negative bacteria (such as E. coli, Klebsiella, and Enterococcus), Gram-positive organisms (especially β-hemolytic Streptococcus), and anaerobes (including Bacteroides and Clostridium).5,19 A broad-spectrum coverage that includes the aerobic spectrum is appropriate, typically a β lactam antibiotic, such as penicillin, and an aminoglycoside, such as amikacin. Although penicillin drugs have good anaerobic coverage, many strains of Bacteroides are resistant to it. In cases in which gas shadows are observed sonographically, additional anaerobic coverage with metronidazole is probably warranted.1

For congenital patent urachus and many milder cases of patent urachus secondary to omphalitis, local therapy (chemical cautery with silver nitrate, topical procaine penicillin G,8 and thermocautery)20 is often curative, but caution must be used not to place anything further than 1 cm into the stump. Treatments that cause necrosis may also predispose to further bacterial infection.21

PROGNOSIS

An early study reports a guarded prognosis with a survival rate of 66.6% in foals treated surgically and 42.9% treated with antibiotic therapy alone (Figure 12-10).8 Advances in therapeutic techniques have improved the overall survival rates to 87%. Nonsurvivors died of causes unrelated to the umbilical infection.15 Severe concurrent disease such as sepsis or multiple joint arthritis, as well as the presence of hepatic abscessation, are suggestive of a poorer outcome.5