1 Assessing the Newborn Foal

Case 1-1 Normal Foal

At 340 days of pregnancy, Labour of Love, a multiparous Thoroughbred mare, had been showing signs of impending parturition over the last 5 days. She had a well-developed udder, and “wax” was beginning to form on the ends of her teats. The muscles around her hindquarters appeared to be softer, and her vulva was relaxed. As with her previous pregnancies, this pregnancy had been uneventful. (Figure 1-1)

HORMONAL SIGNALING OF PARTURITION

This is followed by a redirection of steroidogenesis in the last few days prior to parturition. It is thought that increasing levels of cortisol induce 17α hydroxylase. This enhances metabolism of P5 to cortisol, producing a rise in fetal cortisol and a concomitant decrease in maternal progestagens. This rise in cortisol usually occurs in the last 5 days of gestation, continues for a few hours after birth,1,2 and is essential to the viability of the foal.

Normal foals have high progestagen levels at birth, which decrease rapidly in the first few hours after birth (Figure 1-2). Progestagen levels in abnormal and premature foals remain high, and a decrease can be associated with recovery. In foals that do not survive, levels may remain elevated. It is thought that this may be due to blocking of an enzyme, which is necessary for preventing overproduction.3,4

Fig. 1-2 Mean ± s.d. plasma progestagen levels in the normal foal (determined by radioimmunoassay).

From Houghton E et al.: Plasma progestagen concentrations in the normal and dysmature foal, J Reprod Fert Suppl 44:609-617, 1991.

Signs of impending parturition may include relaxation of the muscles of the hindquarters and lengthening of the vulvar lips. During pregnancy, the mammary glands are exposed to high levels of estrogen and progestagens. It is thought that lactation is triggered by the rise in progestagens from about 310 days gestation, then the precipitous decrease 2 to 3 days prior to parturition, combined with increasing prolactin levels during the last week of pregnancy. Udder enlargement usually begins 2 to 3 weeks before parturition. As birth becomes imminent, small amounts of beaded colostrum may form on the tips of the teats. This is called “waxing.” Calcium content of the mammary secretion increases over the last day of pregnancy. Field tests are available to measure calcium in the hopes of predicting when a mare will foal. These tests are not 100% reliable.5 It is important to remember that each mare is an individual and that not all “wax up.” Also, some don’t enlarge the udder until days before the birth. Occasionally a mare will actually produce and leak milk 1 to 5 days before the birth. This is of grave concern because the potential loss of colostrum for the foal and failure of passive immunoglobulins.

The production of colostrum is a unique event. It is a vital component that enhances the efficacy of the foal’s naïve immune system. Maternal immunoglobulins are concentrated in a nonspecific way in the mammary gland. Colostrum provides immuno-globulins, complement, lysozyme, and lactoferrin and large numbers of B-lymphocytes. It also contains growth factors important in maturation of the gastrointestinal tract. A Thoroughbred mare typically produces 1 to 2 liters of colostrum. (See Chapter 4.)

Ten minutes after the beginning of second-stage labor, a filly was born and rapidly attained a sternal position (see Figure 1-3). A few minutes later the umbilical cord broke with the filly’s first attempts to stand. The filly was moved in front of the mare, and the umbilical remnants were treated with a 0.5% chlorhexidine and surgical alcohol mix. The foal had a suckle reflex present, and the foal made attempts to stand as the mare licked it. Forty-five minutes after birth, the foal was able to stand with a base-wide stance and started typical udder-seeking behavior (Figure 1-4).

TRANSITION TO EXTRAUTERINE LIFE

Stroke volume in the neonate is limited, so cardiac output is rate dependant. There are significant changes in the proportion of blood flow to the various organs at birth. In utero the kidney receives 2% of blood flow, which increases to 8% to 10% postpartum. The lungs only receive 15% in utero, which increases to 100% postpartum.6

The chest wall of the neonatal foal is very compliant, but the lungs are relatively inelastic, which limits tidal volume, increases work of breathing, and lowers functional reserve capacity of the lungs. High respiratory rates help to overcome this. Tidal volume increases by about 20% during the first week; there is a continued rise in PaO2 and an increase in alveolar ventilation. The response to 100% inspired oxygen alters significantly over the first week (Table 1-1).7,8 This results in a significant increase in respiratory reserve by day 7.

Table 1-1 Mean (± sem) PaO2 Values Following 100% Oxygen Administration in Foals Ages 30 Minutes to 7 Days

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Surfactant is present in the lungs from about 300 days gestation; however, a recent study9 has shown that at 2 days after birth, surfactant surface tension is markedly increased (tenfold) when compared with that of 5-day-old foals. Also, the sum of anionic phospholipids is decreased in normal foals when compared with that of adults. In the Thoroughbred, bronchiolar duct endings continue to increase in the foal until about 1 year of age. This continued postnatal development appears to be absent in ponies.10

STAGES OF LABOR

Most Thoroughbred mares foal at night, with 86% occurring between 7 pm and 7 am, and maximal incidence between 10 pm to 11 pm.11 During first-stage labor, coordinated uterine contractions push the allanto-chorion into the dilating cervix; at this stage, the mare starts to become restless and may begin to sweat and walk. First-stage labor ends with rupture of the membranes and release of the allantoic fluid (i.e., “breaking water”). During this first phase of parturition, the front half of the foal starts to rotate from a flexed dorsopubic position to a dorsosacral position with the forelimbs and head extending into the birth canal.12 During second-stage labor, the caudal half of the foal rotates. Although mares can foal in a standing position, most go into lateral recumbency at the start of second-stage labor.

The passage of the foal into the birth canal stimulates oxytocin release, enhancing strong uterine and abdominal contractions that result in rapid expulsion of the foal. The white translucent amniotic sac around the foal’s foot is usually visible at the vulval lips within 5 minutes of the rupture of the allantochorion. The mare often gets up and down and may roll during phase two of parturition, which may help to rotate the foal into a normal presentation.

The contractions are most forceful during delivery of the chest, and the mare usually stops straining as the hips are delivered. The foal is usually delivered within the amnion. Struggling from the foal completes delivery. Second stage labor is usually 20 to 30 minutes, and occasionally longer in primiparous mares. Expulsion of the fetal membranes constitutes third-stage labor and usually occurs within 3 hours of birth.13

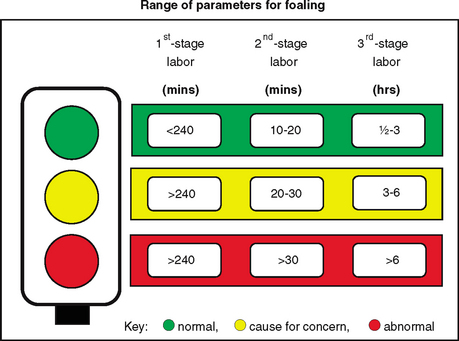

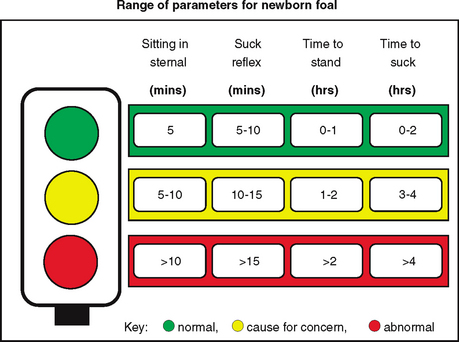

It is important to give owners a timetable for each stage of labor and for certain foal behaviors that they can use to evaluate the progress of labor and the viability of foals (Figures 1-5 and 1-6). If labor doesn’t progress as it should or if the foal fails to stand and suckle within 2 to 3 hours, then veterinary medical intervention is necessary to prevent catastrophic results.

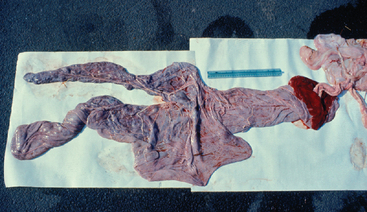

EXAMINATION OF THE PLACENTA

The placenta should be weighed and checked for completeness and any signs of abnormality (Figure 1-7). There is a direct relationship between placental weight and fetal size in healthy foals. The placenta from a normal Thoroughbred weighs 5.6 to 6.3 kg (12.3 to 13.8 lbs), and the placenta from ponies averages 2.2 to 2.6 kg (4.8 to 5.7 lbs).14

The amnion should be bluish white and translucent with prominent tortuous vessels on its surface. “Cigar-ette burn” lesions are not considered significant. The amnion is attached to the cord, which should be of uniform diameter, and the whole cord usually measures 36 to 80 cm long. Cord lengths over 70 cm are more likely to be associated with abnormality.15,16 The umbilical arteries, vein, and urachus comprise the amnionic portion of the umbilicus and usually have a gentle spiral appearance. Excessive twisting of the cord is seen in umbilical torsion and produces a dead or compromised foal.16

Both sides of the allanto-chorion should be examined. The smooth allantoic side has the blood vessels under a thin translucent membrane, giving the surface a whitish appearance. The chorionic side, which is attached to the mare’s uterus, has a diffuse red velvety appearance; the pregnant horn, nonpregnant horn, and body can be readily identified. An uneven red coloration of the chorionic side of the placenta may be due to uneven blood congestion during the birth process. This is normal but must be differentiated from congestion and edema from placentitis.17 (See Chapter 2.)

CARE OF THE UMBILICAL REMNANT

It has been suggested that a concentration of 0.5% chlorhexidine is most effective in reducing bacterial colonization, with a sustained period of activity.18,19 The addition of surgical alcohol will speed drying and sealing of the cord. Alternatively, an antibiotic in alcohol spray or diluted iodine can be applied. However, there is little evidence-based medicine on this subject. Even for human babies, it remains controversial as to which methods best reduce omalophlebitis and associated complications.