Chapter 22 Veterinary Care of Bustards

BIOLOGY

Bustards are small to very large terrestrial birds, chiefly inhabiting open plains and semidesert regions of the world, although some of the African species live in thick thorn scrub. Hunters have reported weights of 24 kg (53 lb) for male great bustards (Otis tarda) (Figure 22-1), which would place the bustard on a level with the mute swan (Cygnus olor) as the heaviest flying bird in the world.11 Fossil records indicate that bustards originated in Africa, from where they diverged to occupy much of the Old World. No bustard species are found in the New World. There are 25 species of bustards,11 but many subspecies are currently being reclassified as separate species, increasing this figure.

Fig 22-1 Great bustard (Otis tarda) at the Great Bustard Trust, U.K. (See Color Plate 22-1.)

(Courtesy Thomas A. Bailey.)

Bustards have long been associated with humans and have been represented in cave drawings, rock engravings, and church mosaics. The word bustard comes from the Latin avis (“bird”) and a lost Spanish word, tarda, which is related to the English word “tread” and signifies “walking.”11 The earliest written accounts of bustards appear in the chronicles of medieval Arab and Western falconers. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, writing in the thirteenth century, was familiar with great bustards and was probably the earliest person to describe anatomic features peculiar to bustards in De Arte Venandi cum Avibus,37 a medieval dissertation on falconry and hunting long recognized as the first zoologic treatise written in the spirit of modern science.

CAPTIVE BREEDING PROJECTS

Bustard populations are under pressure from agriculture, hunting, habitat modification, overgrazing, roads, building, and the spread of overhead cables.11,19 In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in the propagation of bustards in captivity, in particular, the houbara bustard (Chlamydotis undulata), the traditional quarry of Arab falconry, in the Middle East and North Africa. Programs for vulnerable and threatened species of bustards such as the great bustard have been established in Europe and the former Soviet Union, and the kori bustard (Ardeotis kori) (Figure 22-2) in the United States (U.S.). Projects with threatened bustard species aim to produce surplus birds for release into protected areas, thereby supplementing declining wild populations, while houbara bustard projects in the Middle East and North Africa aim to provide surplus birds for sustainable hunting using falcons. Captive breeding programs in the U.S. for kori bustards and buff-crested bustards (Eupodotis ruficrista) aim to maintain populations that are genetically and demographically self-sustaining and do not rely on continued imports from the wild.17 Table 22-1 lists common and species names of bustard typically kept in captivity.

Fig 22-2 Kori bustard (Ardeotis cori) in East Africa. (See Color Plate 22-2.)

(Courtesy Paul Goriup.)

Table 22-1 Average Adult Body Weight of Bustard Species Commonly Kept in Captivity

| WEIGHT (kg) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Species (Scientific Name) | Male | Female |

| Arabian bustard (Ardeotis arabs)11 | 5.7-10.0 | 4.5 |

| Australian bustard (Ardeotis australis)11 | 5.6-8.2 | 2.8-3.2 |

| Great bustard (Otis tarda)11 | 5.8-18.0 | 3.3-5.3 |

| Great Indian bustard (Ardeotis nigriceps)11 | 8.0-14.5 | 3.5-6.8 |

| Kori bustard (Ardeotis kori struthinuculus)* | 10.0-18.0 | 6.0-7.0 |

| Kori bustard (Ardeotis kori kori)† | 7.0-14.0 | 3.0-6.0 |

| Kori bustard (Ardeotis kori kori)‡ | 10.9-9.0 | 5.9 |

| Heuglin’s bustard (Neotis heuglinii)11 | 4.0-8.0 | 2.6-3.0 |

| Nubian bustard (Neotis nuba)11 | 5.4 | ND |

| Houbara bustard (Chlamydotis macqueenii)§ | 1.5-2.5 | 0.8-1.4 |

| Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis)11 | 1.25-1.7 | 1.7-2.25 |

| White-bellied bustard (Eupodotis senegalensis)† | 0.94-1.4 | 0.91-1.16 |

| Black bustard (Afrotis afra)† | 0.7-0.8 | ND |

| Buff-crested bustard (Lophotis gindiana)† | 0.4-0.8 | 0.4-0.6 |

| Little bustard (Tetrax tetrax)11 | 0.79-0.98 | 0.68-0.95 |

ND, No data.

* Subspecies maintained in U.S. zoos.9, 17

† Subspecies maintained at National Avian Research Center (NARC).

UNIQUE ANATOMY

A typical bustard has a short bill and a long, slender neck and is stout bodied, short tailed, and supported on long legs with only three toes. Unlike most bird species, bustards have hexagonal, not transverse-shaped, scales on their legs and no preen glands with which to oil their feathers. They compensate for their missing preen gland by producing powder down, and they maintain their feathers by grooming them with their bill, transferring the powder to all surfaces.11

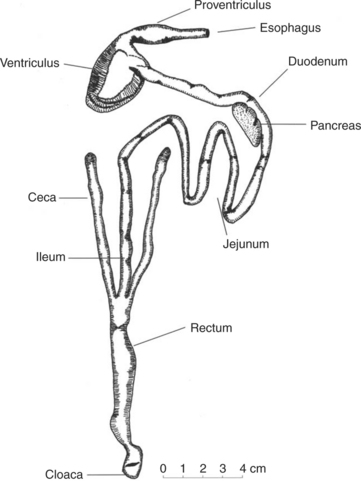

This section describes some unique anatomic features of the bustard alimentary tract. The alimentary tract of all species of bustards consists of a cavum oralis, pharynx, esophagus, proventriculus, ventriculus, small intestine (consisting of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum), large intestine (consisting of paired ceca and a rectum), and cloaca (Figure 22-3).

Fig 22-3 Alimentary tract of adult houbara bustard.

(From Bailey TA, Samour JH, Naldo J, et al: J Anat 191:387-398, 1997.)

The cavum oralis of male kori and great bustards contains a throat sac, or saccus oralis. The opening to the saccus oralis is from a sublingual orifice between the rami of the mandible. It is used as a display chamber during the breeding season in these species. The saccus oralis is absent in many species, including houbara, white-bellied (Eupodotis senegalensis), and buff-crested bustards.6 Other species, such as the Australian bustard (Ardeotis australis), do not possess a true saccus oralis, and inflation of the throat area in this species during courtship is believed to be caused by distention of the esophagus.

Bustards do not possess a crop, and the esophagus connects the pharynx to the gastric region. The bustard proventriculus is small, whereas the ventriculus is comparatively voluminous, probably playing a role in food storage. In the absence of a crop and the presence of a well-differentiated ventriculus, drugs given orally pass rapidly through the esophagus and stomach and are available for absorption from the small intestine. Pharmacokinetic trials with orally administered enrofloxacin and amoxicillin have shown that these drugs are rapidly absorbed from the bustard gastrointestinal tract.1

The ceca of bustards are well developed and indicate the dependence of the family on fibrous parts of plants.11 The large intestine plays a major role in resorption of water. The rectum and cloaca form a greater proportion of the bustard alimentary tract compared with many other avian species, and this may reflect an adaptation for water conservation.

WEIGHT AND GENDER

Adult body weights of bustard species typically encountered in captivity are summarized in Table 22-1. Kori bustard chicks may be trained to stand on scales, reducing the need to handle birds to obtain an accurate weight.17

Adult bustards show sexual dimorphism. There is a seasonal variation in body weight and food intake in some species, including houbara and Australian bustards. Houbara bustards are heaviest in winter, progressively losing weight as summer approaches. Male Australian bustards have a 50% increase in body weight at the end of winter before they begin to display.14 Some smaller species (e.g., white-bellied bustards) may be sexed by differences in head and throat plumage. Larger species show strong, adult sexual dimorphism. Kori bustards are easily sexed at 1 year of age; although the plumage of both genders is similar, males are considerably larger than females. Juvenile bustards may also be sexed using endoscopy after about 6 months of age. Molecular sexing offers many advantages, being noninvasive, and if done from feathers or blood collected from freshly hatched chicks, it may allow different genders to be reared under different protocols.

SPECIAL HOUSING REQUIREMENTS

Differences exist in the housing of bustards both between and within species and according to the region where the birds are maintained in captivity.2 Paillat and Gaucher29 comprehensively reviewed the type and design of facilities for breeding houbara bustards in the Middle East. Great bustards in the United Kingdom (U.K.) have been kept as single-gender groups in 20 30-m grass paddocks topped with nylon netting and as a mixed-gender flock in a large, 4-hectare paddock.3 In the U.S., kori bustards are maintained in outdoor pens that are equipped with heated shed areas, where the birds are housed during periods of inclement winter weather. Bustards should be kept on well-drained ground. All species of bustard are susceptible to frostbite, and supplemental heat must be supplied when temperatures drop below 4°C (39°F). The provision of shade and shelter is important for birds managed outdoors in tropical and temperate climates, respectively, as is the use of predator-proof fencing material. It should be remembered that in naturalistic aviaries, wild birds, including pigeons and doves, can be a potential source of disease for captive bustards (Figure 22-4)

NUTRITION

Diet of Free-Ranging Birds

Most bustards, including houbara bustards, are opportunistic omnivores, and in the wild their diet reflects the local and seasonal abundance of plants and small animals.19,36 Kori and black-bellied bustards (Lissotis malanogastor) will even eat carrion and have been found at the side of roads eating corpses of birds.11 Plants appear to be a more important source of food for houbara bustards during winter and early spring, whereas animals, mostly invertebrates and small vertebrates, are more likely to be consumed in the late spring and summer.19 In the wild, houbara bustard chicks are fed mainly insects and small reptiles. Box 22-1 summarizes the diets in the wild of some species typically kept in captivity.

Box 22-1 Summary of Wild Dietary Requirements of Some Bustard Species Kept in Captivity

Data from Collar NJ: Otididae (bustards). In Del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J: Handbook of birds of the world. Hoatzin to auks, Barcelona, 1996, Lynx Edicions, pp 240-275; Johnsgard PA: Bustards, hemipods and sandgrouse. In Birds of dry places, New York, 1991, Oxford University Press, pp 106-115; and Tigar BJ, Osborne PE: Ibis 142:466-475, 2000.

Diet of Captive Birds

In captivity, bustards have been fed mice, mealworms, crickets, apple, cabbage, chopped greens, and bustard pellets, game bird pellets, or a mixture of crane and ratite pellets.35 Captive bustards also eat invertebrates attracted to vegetation in naturalistic aviaries. Beef mince has been used to replace mice or mealworms if either component is unavailable. Meat is a perishable food and, particularly in hot climates, needs to be handled carefully to prevent spoilage.17

Kori bustards kept in U.S. zoos are fed horsemeat in addition to mice, and the meat is supplemented with either crane and ratite pellets or game bird pellets.17 The mixture may be made into small meatballs and hand-tossed to each bird. This method of feeding facilitates close inspection of each bird. Kori bustards at the San Diego Zoo are fed on a mixture of a weight control diet for dogs (IAMS), Zoo Carnivore Diet 5 (Natural Balance), mealworm larvae, crickets, and whole adult mice (Edwards, personal communication). To encourage natural foraging behavior, supplement the daily diet and provide a form of enrichment; chopped green beans, hard-boiled egg, blueberries, giant grasshoppers, mincemeat, meatballs, lizards, feeder goldfish, cherry tomatoes, grapes, grains, shelled peanuts, sunflower seeds, and honeysuckle flowers are provided to kori bustards.17

In Europe, great bustards have been fed proprietary concentrate pellets, Zoo A diet (Mazuri Zoo Foods, U.K.), a proprietary crane diet, and a formulated bustard diet (Special Diet Services, U.K.), and fresh cabbage and cauliflower were fed ad libitum. Locusts, crickets, mice, dog food, insectivorous bird food, mealworms, spinach, cress, spring greens, and sprouting broccoli have been fed to increase the condition of the birds at the Zoological Society of London.3

In the Middle East at the National Avian Research Center (NARC) and the National Wildlife Research Commission (NWRC), maintenance pellets (14% protein) are fed to houbara bustards outside the breeding season, and productioner pellets (22% protein) are fed during the breeding season.29,35 Live food (mealworms or crickets) may be supplemented as part of taming protocols.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree