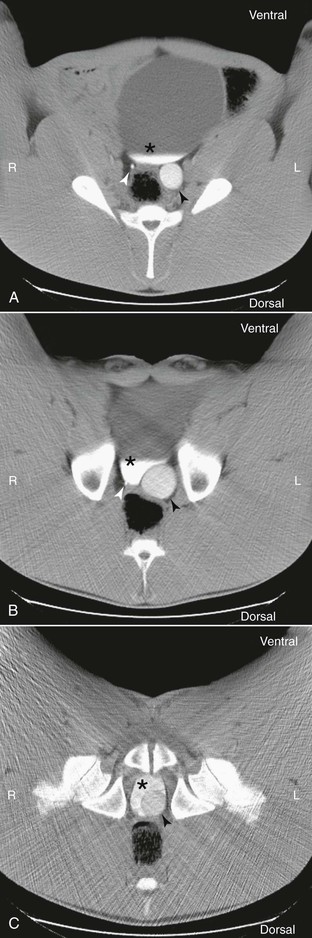

Michelle C. Coleman Ureteral defects and tears, or ureterorrhexis, are uncommon causes of uroperitoneum in foals and adult horses. Only a few cases have been reported in neonatal foals, and even fewer cases have been reported in adult horses. No sex or breed predilection has been recognized. Defects may be unilateral or bilateral, and multiple defects may be seen in one ureter. Most defects are observed in the proximal half of the ureter, near the kidney. Urine accumulates initially in the retroperitoneal space, but rupture of the retroperitoneal tissues can result in uroperitoneum. Because urine leakage develops more slowly than that observed following rupture of the bladder, clinical signs are often delayed until 5 to 10 days of age in affected foals. Clinical signs include poor appetite, depression, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and diarrhea. Vaginal mucosal bulging may be observed in fillies. Hyperkalemia develops and may result in muscle fasciculations. Clinicopathologic findings are consistent with uroperitoneum and include hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, hypochloridemia, and azotemia. In adult horses, the distal portions of the ureters may be evaluated by a skilled ultrasonographer using transrectal ultrasound. If the fluid remains retroperitoneal, ultrasonographic findings may include fluid accumulation around the kidney and dilation of the renal pelvis. If the retroperitoneal membranes rupture, uroperitoneum may be observed. In this instance, the peritoneal fluid creatinine-to-serum creatinine ratio will be greater than 2 : 1. Additional diagnostic tests to aid in localization of the defect include positive contrast cystography, retrograde pyelography, and excretory urography. Catheterization of the ureters (performed by advancing a catheter in a retrograde direction from the bladder toward the renal pelvis) and use of contrast material may be necessary to definitively localize the defect. Although a developmental anomaly is often suspected, the pathophysiology of ureteral defects in foals is poorly understood. In one study, trauma was suspected in all cases reported in adult horses. In humans, retroperitoneal accumulation of urine from disruption of the ureter often develops after blunt abdominal trauma. Several reports have described ureteral defects in foals after suspected traumatic injury, including blunt trauma from the dam and foaling trauma. Necropsy and histologic findings in those cases supported a traumatic etiology. Surgical intervention is necessary to correct the defect and has been successful in several cases. Surgical options include ureteral stenting with or without primary ureterorrhaphy, diversion of the urine through a percutaneous nephrostomy while the tear heals by second intention, ureteroneocystostomy, and ureteronephrectomy. Horses with uroperitoneum are poor anesthetic candidates because of metabolic and cardiovascular instability. Correction of electrolyte imbalances before surgery is recommended. Postoperative complications include ascending urinary tract infection, ureteral or urinary bladder catheter occlusion or complete failure of these catheters, rupture of the urinary bladder, ureteritis, leakage of urine around the suture material or stent, and rerupture of the ureter. The prognosis is guarded; however, if repair is successful, the long-term prognosis can be favorable. Ureteral ectopia is a congenital anomaly of the terminal segment of one or both ureters in which the ureteral orifice is located caudal to the trigone of the urinary bladder. The anomaly is thought to be caused by abnormal embryologic development of the metanephric and mesonephric ducts. No breed or sex predilection has been reported, but most of the cases reported were females. This may be because incontinence is easier to recognize in females. The most common clinical sign is continuous or intermittent urinary incontinence that has been observed since birth in the absence of other neurologic signs; however, clinical signs may vary depending on sex, site of termination of the ureters, and whether there is unilateral or bilateral involvement. Perineal dermatitis often results secondary to urine scalding. The remainder of the physical examination and serum biochemistry analysis are typically unremarkable in the absence of secondary complications. Confirmation of an ectopic ureter can be achieved with several different imaging modalities. In females, visual examination of the vestibule of the vagina with a speculum can be initially performed to evaluate urine flow from the ureters. The ureters can be directly viewed with cystoscopy. Intravenous administration of dyes, including phenolsulfonphthalein (1 mg/kg; color, red), azosulfamide (2 mg/kg; color, red), sodium fluorescein (10 mg/kg; color, yellow-green), and indigotindisulfonate (0.25 mg/kg; color, indigo), can be used to discolor the urine to help locate the ureteral openings. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, ultrasound-guided pyelography, and excretory urography have also been used with success in identifying an ectopic ureter. Contrast radiographic imaging may be of limited value, and computed tomography (Figure 107-1) and magnetic resonance imaging are preferred approaches to obtain the best detail about the course of the ectopic ureters from the kidney to the lower urinary or reproductive tract. Nuclear scintigraphy has been used to help define renal function before correction of the ectopia, but yields limited anatomic detail regarding the terminal end of the ureter. Regardless of the diagnostic approach used, accurate localization of the terminal aspect of the ureter and determining whether the defect is unilateral or bilateral are essential for choosing the most appropriate surgical technique. In addition, before surgical repair, it is important to determine whether a urinary tract infection is present and if renal function is normal. The most common postoperative problem in dogs is urinary incontinence; therefore determining whether detrusor and ureteral sphincter function is normal is recommended before surgery. This can be simply evaluated by infusing saline into the bladder and monitoring for incontinence of the infused fluid. Cystometrography, which measures bladder volume and pressure, may be performed in dogs for more complete assessment.

Ureteral Disease

Ureteral Defects or Tears

Ectopic Ureter

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ureteral Disease

Chapter 107

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue