CHAPTER 61 Reproductive Health Programs for Dairy Herds: Analysis of Records for Assessment of Reproductive Performance

RECORDS AND MONITORING

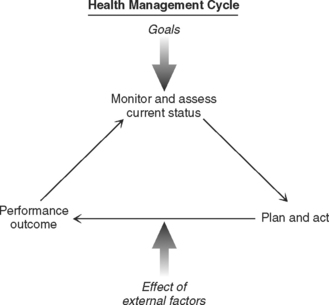

The effective use of records is a cornerstone of modern dairy production medicine. Records provide access to the performance results of a dairy’s management and serve as a major source of diagnostic information when problems arise. As veterinary service to dairy farms has matured, practitioners have become more involved in herd-level analysis, management consulting, and problem solving. Monitoring is an essential component of any system that must respond to external influences (Fig. 61-1).1–3 A parameter of the system is measured and compared with standards, goals, or past performance. If the parameter does not meet the goal, then plans are made and actions are taken (usually including collection of more diagnostic information). Because of both the action taken and the external influences on the system, a result is achieved. The result becomes the new status and the cycle begins again. Even though this activity is routine in most veterinary reproductive programs, in many cases it is not as fully developed or deliberately documented as might be most useful to the client.

Fig. 61-1 Role of monitoring in farm management feedback cycle.

(Adapted from Radostits O, Leslie K, Fetrow J: Herd health: food animal production medicine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1994.)

Although attempts have been made to arrive at a single “index” that will assess the performance of a dairy’s reproductive program, none are adequate alone.2 Evaluating reproduction involves a complex set of issues that are to some degree unique to the particular dairy. Attempts have been made to develop expert computerized systems to evaluate reproduction,4 but none are in widespread use at the current time.

Viewed from another perspective, monitoring can be applied to two classes of information:

PITFALLS OF MONITORING PARAMETERS

Herd size can have a dramatic effect on the variation and computation of averages. In a 50-cow herd with 25 confirmed pregnant animals, a single cow with 350 days open increases the average days open of the currently pregnant cows by 10 days. If this cow is then sold, the average of the remaining 24 will drop by 10 days (example assumes average days open of 100 days). If the dairy farmer is unaware of this, false credit for a positive result may be given to an irrelevant intervention. Conversely, two animals conceiving at 37 days would drop the average of the 27 pregnant animals by 5 days. At the other extreme of herd size, in very large herds with many cows contributing to the parameter, the average in any time period will tend to regress toward the long-term mean, obscuring problem cows that as individuals can be quite costly. Herd size effects cannot be avoided when averages are calculated; the practitioner must be aware of the possible pitfalls and use judgment when analyzing reproductive records.

Terminology Issues

There are many terms used in describing reproductive programs, terms that have survived and become part of the everyday lexicon of dairying. Unfortunately, some of these terms are not consistent with standard meanings of words. Although it is likely that many terms will go on being used even though improper, it would serve the industry and profession if everyone could be a bit more precise in how words are used. Specifically, rate is a term often misapplied to reproductive parameters. A rate is formally a measure of an event or statistic per time period. Thus, miles per hour or deaths per 1000 cows per year are rates. Unfortunately, many parameters associated with reproduction are discussed as rates but in fact are not rates. For example, conception rate is not a rate (no dimension of time). Conception rate (pregnancies per insemination) is a risk (proportion of a population with some particular characteristic7). Older terms with widely accepted meanings are probably best left as is. New terms should be more carefully chosen.

GENERAL GOALS OF A REPRODUCTIVE PROGRAM

It has long been known that there is an important economic advantage to be gained by efficient reproduction in dairy herds.8–12 The economic effects of a sound reproductive program include increased milk by returning cows sooner to the earlier, more profitable phase of their lactation, increased numbers of replacement heifers and bull calves born, reduced costs of reproductive disease and reduced costs from culling, reduced nonproductive days due to extended dry periods, and increased rate of genetic gain.

MONITORING STATUS AND HERD REPRODUCTIVE TRENDS

Many parameters are used to monitor reproductive status and trends on the dairy farm. Some of these goals are shown in Table 61-1. For the most part, these are the traditional monitoring parameters for dairy reproduction. These herd goal levels must be applied with caution and may not be the appropriate alerting levels for management intervention on an individual cow basis. Several reviews of these parameters and their application have been written, so what follows is only a brief outline of the major parameters.5,14–20

Overall Reproductive Efficiency

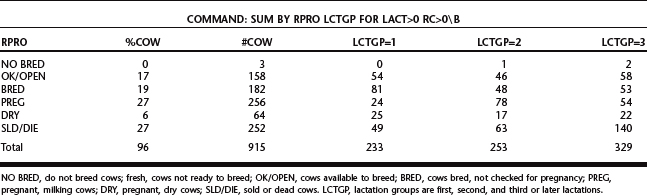

Herd Distribution of Cows by Reproductive Status

Perhaps the best starting place for evaluating a dairy’s reproductive status is simply a breakdown of cows by reproductive status and lactation (see Table 61-121). Cows are split into the following groups:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree