Chapter 52 Prokinetic Agents

Dopaminergic D2 Antagonist Drugs

Metoclopramide and Domperidone

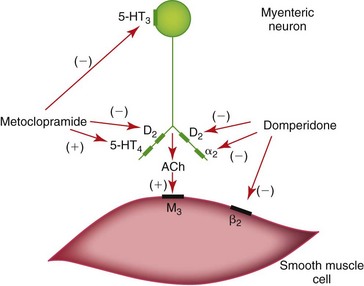

The dopaminergic D2 antagonists are a group of drugs with gastrointestinal prokinetic and antiemetic effects at peripheral (prokinetic) or central (antiemetic) dopamine D2 receptors (Table 52-1, Figure 52-1).1 The best representatives in this classification, metoclopramide and domperidone, reverse gastric relaxation induced by dopamine infusion in dogs, and they abolish vomiting associated with apomorphine therapy. Although the role of dopamine receptors in chemoreceptor trigger zone–induced vomiting is fairly well established, there is no definitive evidence that inhibitory dopaminergic neurons regulate gastrointestinal motility. The prokinetic effects of metoclopramide and domperidone thus may not be readily or exclusively explained by dopamine receptor antagonism. Some dopaminergic antagonists (e.g., metoclopramide) have other pharmacologic properties, for example, 5-HT3-receptor antagonism and 5-HT4-receptor agonism. Domperidone also has α2– and β2-adrenergic receptor antagonistic effects. The characterization of these drugs as dopaminergic antagonists is convenient but may not properly describe their overall in vivo effects.

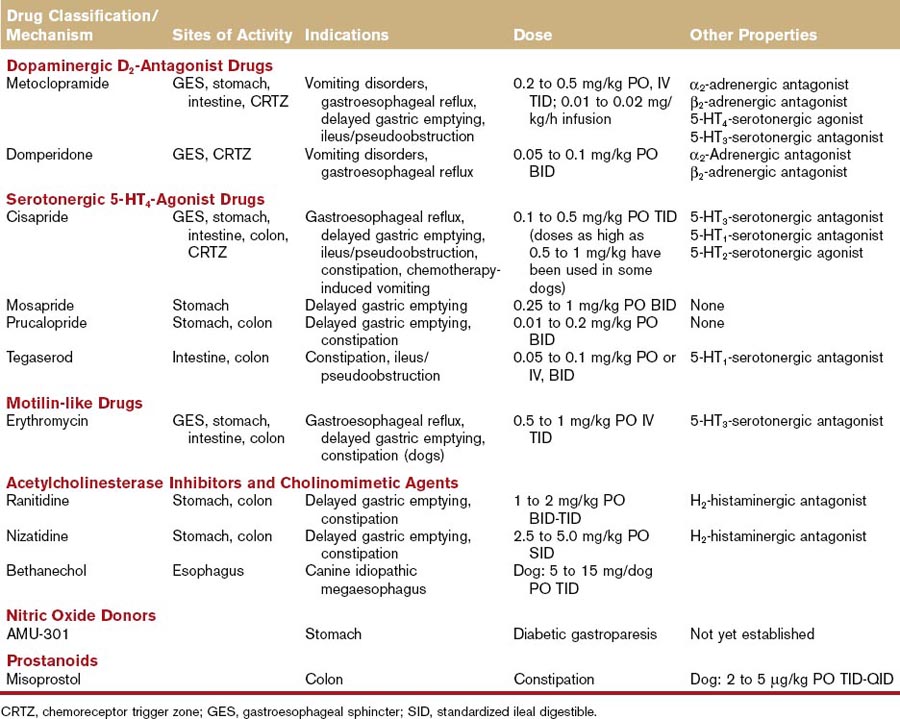

Table 52-1 Mechanisms, Sites of Activity, Indications, and Doses of Currently Available Gastrointestinal Prokinetic Agents

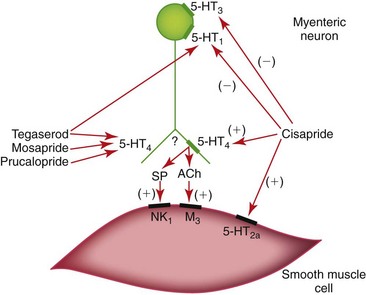

Figure 52-1 Dopaminergic regulation of gastrointestinal motility and sites of action of metoclopramide and domperidone.

Gastroesophageal Sphincter Disorders

The gastroesophageal sphincter prevents reflux of gastrointestinal contents into the esophageal body.2,3 Reflux of gastric H+ and pepsins, and of duodenal bicarbonate, bile salts, and proteases, induces chemical injury and inflammation of the esophageal mucosa.3 Gastroesophageal sphincter tone appears to be under the regulation of dopaminergic neurons as both metoclopramide and domperidone increase sphincter tone. The gastric prokinetic effect of metoclopramide, although moderate, may also help to reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of reflux episodes.

Gastric-Emptying Disorders

Metoclopramide increases the amplitude and frequency of antral contractions; inhibits fundic receptive relaxation; and coordinates gastric, pyloric, and duodenal motility, all of which result in moderate acceleration of gastric emptying.4,5 Metoclopramide appears to have continuing clinical application as a gastric prokinetic agent in the dog and cat, although the serotonergic agonists are clearly more potent. Domperidone appears to be less effective as a gastric prokinetic agent. Although effective in humans, domperidone actually decreases the frequency of corporeal, pyloric, and duodenal contractions and deteriorates antropyloroduodenal coordination in the dog by decreasing the frequency of contractions spreading from the antrum or pylorus to the duodenum.5

Small Intestinal Transit Disorders

Metoclopramide and domperidone are generally considered less effective in the management of the small intestinal transit disorders. Metoclopramide enhances antropyloroduodenal coordination in the dog and may be effective when delayed gastric emptying is a result of poor antropyloroduodenal coordination.6 Domperidone has no documented effects on small intestinal transit.

Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone–Induced Emesis

The antiemetic effects of metoclopramide and domperidone are attributed to their central effects at the chemoreceptor trigger zone.7 The antiemetic effect of metoclopramide is more important than its prokinetic effect.1,7 Despite long-standing usage by small animal veterinarians, metoclopramide is not a very potent gastrointestinal prokinetic agent. Domperidone is 12 to 25 times more potent than metoclopramide and 50 to 60 times more potent than prochlorperazine in attenuating apomorphine-induced vomiting.

Serotonergic 5-HT4-Agonist Drugs

Drugs acting on gastrointestinal 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT or serotonin) receptors have potent motility effects (see Table 52-1, Figure 52-2).8 Serotonergic drugs that bind 5-HT4 receptors on enteric cholinergic neurons induce depolarization and contraction of gastrointestinal smooth muscle. These drugs are not entirely selective for the 5-HT4 receptor, however. Some of the putative 5-HT4-receptor agonists also have 5-HT1 and 5-HT3 antagonistic effects on enteric cholinergic neurons, and direct noncholinergic (perhaps 5-HT2a) effects on colonic smooth muscle. Cisapride, mosapride, prucalopride, and tegaserod are the best examples in this classification. Cisapride and tegaserod have been withdrawn from several international markets because of their effect(s) on myocardial Q-T interval prolongation, although both remain available through compounding pharmacies. Mosapride is available in Japan (Pronamid, DS Pharma) and prucalopride is available in Europe (Resolor, Movetis).

Cisapride

Cisapride was widely used in the management of canine and feline gastric emptying, intestinal transit, and colonic motility disorders throughout most of the 1990s.9,10 Cisapride was withdrawn from the American, Canadian, and certain West European markets in July 2000 following reports of untoward cardiac side effects in human patients. Cisapride causes Q-T interval prolongation and slowing of cardiac repolarization via blockade of the rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium channel (IKr).11 This effect may result in a fatal ventricular arrhythmia referred to as torsades de pointes.11 Similar effects have been characterized in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers, but in vivo effects have not been reported in dogs or cats. The withdrawal of cisapride has created a clear need for new gastrointestinal prokinetic agents, although cisapride continues to be available from compounding pharmacies.

Gastroesophageal Sphincter Disorders

Cisapride is indicated for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux because it stimulates gastric emptying and increases gastroesophageal sphincter pressure. Comparative studies have shown that cisapride is more potent than metoclopramide in stimulating gastric emptying and increasing gastroesophageal sphincter pressure. Cisapride can be used in conjunction with chemical diffusion barriers (e.g., sucralfate) and gastric acid secretory inhibitors (e.g., H2-receptor antagonists; H+,K+-adenosine triphosphatase [ATPase] inhibitors) in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux.12–14

Cisapride stimulates distal esophageal peristalsis in those animal species (e.g., cat, human being, guinea pig) in which the distal esophageal muscularis is composed of smooth muscle. The obvious exception is the dog, a species in which the entire esophageal body is composed of striated muscle. It has been suggested that cisapride might improve esophageal peristalsis in dogs affected with idiopathic megaesophagus. This would not appear to be a rational clinical application of the drug, because a smooth muscle prokinetic agent would not be expected to have much effect on striated muscle function. Indeed, the prokinetic effect of cisapride in the esophagus of human beings or cats is confined to the distal esophageal body at the transition zone from striated muscle to smooth muscle. Cisapride has no effect on proximal esophageal peristalsis in these species. Furthermore, 5-HT stimulates contraction of canine gastroesophageal sphincter smooth muscle, but is without effect on canine esophageal body striated muscle.15 Thus, cisapride cannot be recommended for the treatment of idiopathic megaesophagus in dogs. Indeed, cisapride-induced increases in gastroesophageal sphincter pressure could diminish esophageal clearance and worsen clinical signs in dogs affected with idiopathic megaesophagus.

Gastric-Emptying Disorders

Cisapride accelerates gastric emptying in dogs by stimulating pyloric and duodenal motor activity, by enhancing antropyloroduodenal coordination, and by increasing the mean propagation distance of duodenal contractions.5,16 Cisapride appears to be superior to metoclopramide and domperidone in stimulating gastric emptying. Dosages of cisapride in the range of 0.05 to 0.2 mg/kg enhance gastric emptying in dogs with normal gastric emptying. Dosages in the range of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg are needed to enhance gastric emptying in dogs with delayed gastric emptying induced by α2-adrenergic agonists, dopamine, disopyramide, or antral tachygastria.9,10

Small Bowel Motility Disorders

Cisapride stimulates jejunal spike burst migration, jejunal propulsive motility, and antropyloroduodenal coordination following intestinal lipid infusion in the dog.6,17 Thus, cisapride would appear to have a rational place in the treatment of postoperative ileus and intestinal pseudoobstruction. Well-designed clinical trials and evidence-based data are required to determine the effectiveness of cisapride in the treatment of these disorders.

Colonic Motility Disorders

Cisapride stimulates colonic motility,18,19 and would appear to have a rational place in the treatment of idiopathic constipation. Disruption of the normal colonic motility patterns results in constipation in domestic cats. Cisapride improves colonic motility in cats that are mildly or moderately affected with idiopathic constipation; cats with long-standing hypomotility and dilation are usually less responsive. A recent evidence-based data review of cisapride’s efficacy in the treatment of human constipation and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome was carried out by the Cochrane Collaboration.20 These authors concluded, “no clear benefit could be demonstrated with cisapride.”20

Cis-Platinum–Induced Emesis

Cis-Platinum-induced emesis is mediated by 5-HT3 serotonergic receptors, either in the chemoreceptor trigger zone (cat) or in vagal afferent neurons (dog). Selective antagonists of the 5-HT3 receptor (e.g., ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron, dolasetron) abolish vomiting associated with cis-platinum chemotherapy. Cisapride antagonizes these 5-HT3 receptors and inhibits vomiting associated with cis-platinum chemotherapy. The potency of cisapride’s 5-HT3 antiemetic effect (median effective dose [ED50] = 0.6 mg/kg IV; ED100 = 2.6 mg/kg IV) is less than its 5-HT4 gastric prokinetic effect. Thus, cisapride could be recommended as an antiemetic agent for the cancer chemotherapy patient only if ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron, or dolasetron were not immediately available or were too cost prohibitive.7 Metoclopramide is equipotent with cisapride in inhibiting cis-platinum emesis, but it has the distinct disadvantage of adverse central nervous system side effects, for example, drowsiness, extreme weakness, and body tremors. Cisapride has no effect on nausea and vomiting mediated by dopaminergic D2 receptors (e.g., apomorphine, uremia) or histaminergic H1 receptors (e.g., motion sickness).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree