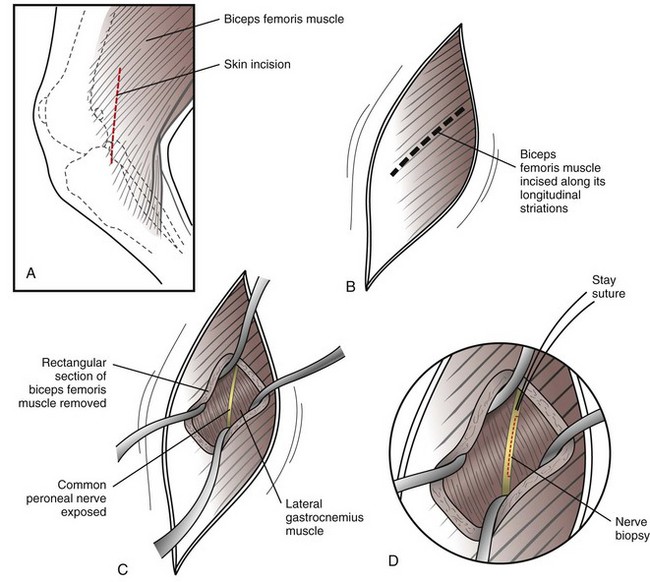

Chapter 44 Position the patient in lateral recumbency and aseptically prepare the pelvic limb as you would for stifle surgery (see p. 1331). Prior to making the skin incision, palpate for the peroneal nerve so that the nerve will be in the region of your surgical approach. Make a vertical skin incision caudal to the patellar ligament, from a few centimeters proximal to the level of the patella to a few centimeters distal to the tibial tuberosity. Make the incision approximately 2 cm caudal to the level used to access the stifle joint (see p. 1331). Use a blade or Metzenbaum scissors to expose the biceps femoris muscle and fascia. Pull up a portion of this muscle with DeBakey forceps and incise the muscle full thickness along its longitudinal striations using Metzenbaum scissors. Continue the incision until a digit can be placed beneath the muscle to palpate the underlying peroneal nerve. Using either a No. 11 blade or Metzenbaum scissors, remove a rectangular section of the biceps femoris muscle (at least 2 cm in length). Identify the underlying peroneal nerve and carefully free a segment of the nerve from surrounding fascia. Retract the edges of the incised biceps femoris muscle with Gelpi retractors to facilitate exposure of the common peroneal nerve (Fig. 44-1). Place a stay suture in the edge of the nerve at the proximal site of the planned biopsy, using 6-0 polydioxanone. While applying gentle tension to this suture, incise (with a new No. 11 blade) the nerve medial to the stay suture knot to begin the nerve biopsy. Do not remove more than one third of the width of the nerve at the biopsy site. Using either the No. 11 blade or fine tenotomy scissors, remove a longitudinal strip of the peroneal nerve (1 to 3 cm, depending on patient size) for biopsy. If a distal neuropathy is suspected, procure a second biopsy specimen from the cranialis tibialis muscle. Close the site routinely. Specific Diseases In addition to the historical complaints listed here, the nature of appendicular (limb) muscle weakness is variable in both distribution and severity. The clinical features of the different forms of acquired MG are provided in Box 44-1. Dogs and cats with MG typically do not have specific neurologic deficits but display varying levels of weakness. It is common for pelvic limb weakness to be the main (sometimes the only) clinical manifestation in dogs with MG; this feature often leads to misdiagnosis of MG as either a myelopathy or pelvic limb musculoskeletal disorder.

Peripheral Nervous System Disorders and Diagnostic Techniques

Muscle and Nerve Biopsy

Acquired Myasthenia Gravis

Diagnosis

Physical Examination Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Peripheral Nervous System Disorders and Diagnostic Techniques