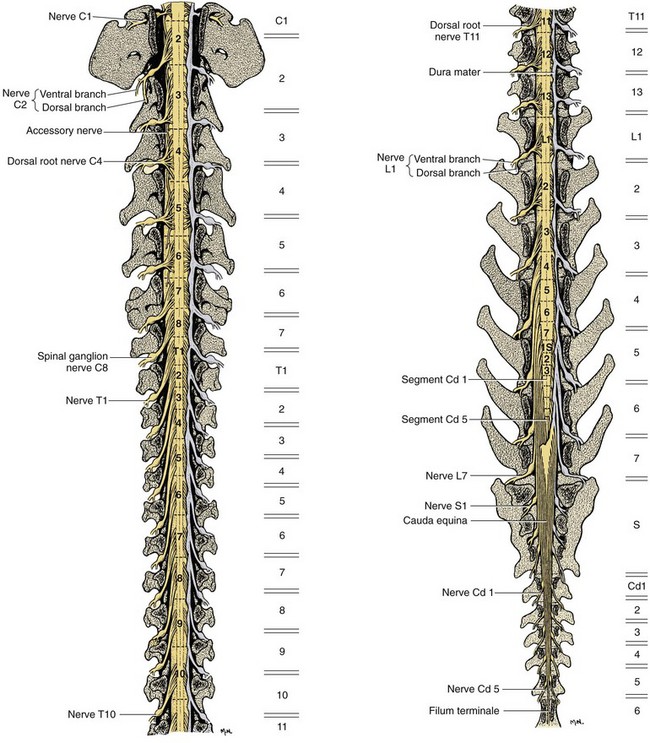

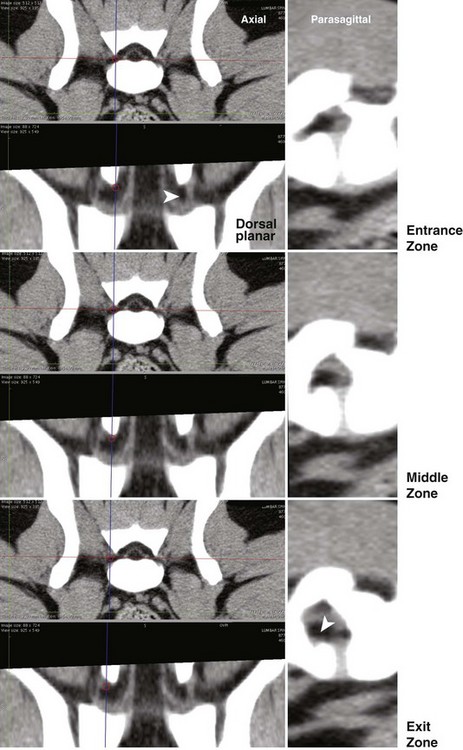

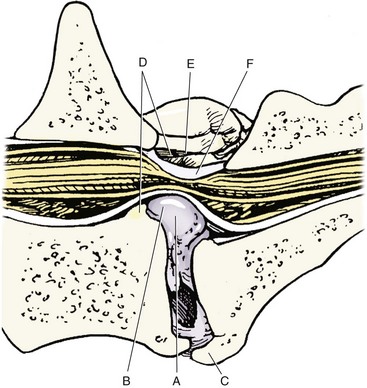

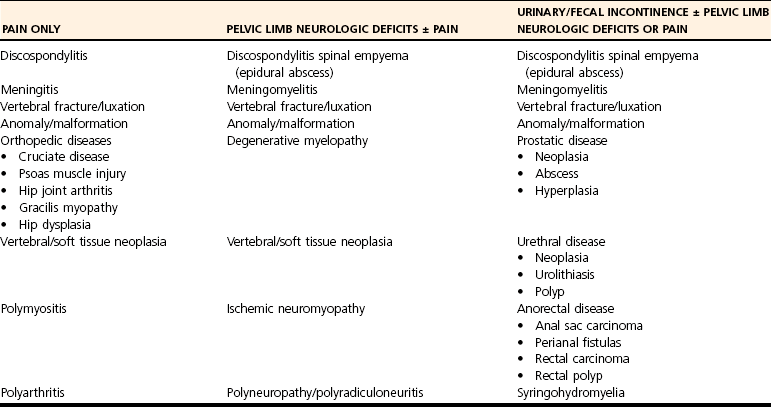

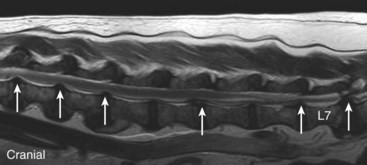

Chapter 33 Cauda equina syndrome is a collective term used to describe the clinical signs resulting from a variety of compressive, inflammatory, infiltrative, malformative, or vascular diseases affecting the nerve roots of the cauda equina. The most common cause of cauda equina syndrome seen in clinical practice is degenerative lumbosacral stenosis.46,48 We will use the term lumbosacral disease to encompass a number of degenerative pathologic processes that involve the nerve roots of the cauda equina (L7 to caudal). Synonyms for lumbosacral disease include degenerative lumbosacral stenosis, lumbosacral instability, and lumbosacral spondylopathy. The cauda equina is anatomically defined as the terminal portion of the spinal cord, the conus medullaris, and the leash of trailing nerve roots that traverse caudally within the lumbar and sacral vertebral canal from the conus medullaris (Figure 33-1).12 Because of the differential growth rates of the skeleton and spinal cord, the cranial anatomic boundary of the cauda equina is variable and dependent on the size of the dog, with termination of the spinal cord occurring anywhere from the L4 vertebral body region (large/giant breeds of dogs) to the L6 (dogs <15 kg) or L7 (toy dog breeds and cats) vertebral body levels.12 The dural sac extends 1 to 2 cm farther caudally than the terminal portion of the conus medullaris in most animals.12 The specific nerves that form the cauda equina are the L7, S1, S2, S3, and caudal nerves 1-5, each of which may be affected in animals with lumbosacral disease (see Figure 33-1). Within the vertebral canal, the nerve roots of the cauda equina are individually covered with meninges and are collectively bordered dorsally by the laminae and ligamentum flavum (interarcuate ligament), dorsolaterally by the articular processes and joint capsules, laterally by the pedicles, and ventrally by the L7 and S1 vertebral bodies, dorsal longitudinal ligament, and dorsal annulus fibrosus of the L7-S1 disc. Cauda equina nerve roots course obliquely and caudally within the vertebral canal, residing within the lateral recess, which is formed by the articular processes and pedicles, immediately before exiting their respective intervertebral foramina.26 The intervertebral foramina are short canals through which nerve roots and their accompanying radicular branches of spinal arteries and veins course. From medial to lateral, these neurovascular structures course through entrance, middle, and exit zones of the intervertebral foramen (Figure 33-2).26,53 The intervertebral foramina are defined by the articular processes and joint capsule, and by the pedicles, vertebral body, and dorsal portion of the intervertebral disc (see Figure 33-2). Commonly incriminated abnormalities that may result in neural or vascular compression of the cauda equina include the following (Figure 33-3): Hansen type II intervertebral disc disease, congenital osseous stenosis of the vertebral canal or foramina, sacral osteochondrosis, proliferation of the joint capsules or ligaments, osteophytosis of the articular processes, epidural fibrosis, and instability or malalignment/subluxation of L7-S1.18,24,26,29,45 Synovial and ganglion cysts, as well as congenital malformations associated with tethered cord syndrome, have also been reported occasionally to cause clinical signs of lumbosacral disease.14,47,52 Given that the lumbosacral portion of the vertebral column is a highly mobile functional unit, it is postulated that instability of this region plays a role in the pathogenesis of numerous degenerative processes (e.g., joint capsule hypertrophy, subluxation, osteophytosis, spondylosis deformans) that may occur in the lumbosacral disease syndrome (see Figure 33-3). These degenerative conditions may perpetuate the progression of disease by further altering the biomechanics of the vertebral column in affected dogs.17,35,45 However, because motion of the lumbosacral junction is complex,2 the potential effects of these pathologies, singly or in combination, on the pathogenesis of lumbosacral disease are currently poorly understood. Practical, accurate, and repeatable objective criteria (clinical, diagnostic imaging, or pathologic) that allow for documentation of lumbosacral instability or its pathologic effects are currently lacking; this complicates all aspects of management of lumbosacral disease. Mechanically compressive radiculopathy can produce signs of motor weakness, pain, or other alterations in the sensorium through a variety of complex morphologic and functional neuropathologic mechanisms. The specific pathologic events that contribute to the development of clinical disease are at least partially dependent on the severity of radicular compression and on whether the compression is continual or intermittent.44 Compression resulting in physical deformation of nerve roots can cause demyelination and axonal loss, and can induce inflammation.30 Release of numerous proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-beta, occurs after compressive radiculopathy, and these biochemical events function to perpetuate the disease by acting in autocrine and paracrine fashions locally and within the spinal cord.43 Cytokine upregulation is an important mechanism in the induction and evolution of neuropathic pain and the development of spinal sensitization associated with radiculopathy, via activation of spinal cord astrocytes and microglia.43 Compressive radiculopathy may also compromise nerve root microcirculation, which can induce or exacerbate intraneural edema.30,44 Experimental canine models of chronic lumbar compressive radiculopathy have produced spinal neuronal degeneration that can occur in anterograde, retrograde, and transneuronal fashions, resulting in extensive damage to dorsal root ganglia, ascending sensory tracts, ventral horn motor neuronal pools, and segmental interneurons involved in the lumbosacral spinal cord circuit.31,34 Young adult, male, large-breed (especially German Shepherd) dogs are predisposed to the development of lumbosacral disease, although dogs of any age or breed may be affected.7,8 The use of dogs in activities that involve heavy work or training is another reported risk factor.25 Lumbosacral disease associated with Hansen type II intervertebral disc disease, osseous stenosis, malformations, and transitional vertebrae has also been reported sporadically in cats.19,21 Clinical signs of lumbosacral disease are heterogeneous and can be static or intermittent and vague or nonspecific. Signs consistent with lower lumbar or pelvic limb pain are common historical complaints and can be protean in nature. Overt clinical manifestations of pain or paresthesia range from crouched pelvic limb posture (Figure 33-4), pelvic limb lameness, and pelvic limb root signature to self-mutilation of the limbs, genitals, or tail. Pelvic limb signs may be unilateral or bilateral. Canine athletes and working dogs may be reluctant to jump or work, or may manifest with variably severe limb dysfunction that is exacerbated by activity. Animals may also present with intermittent claudication, which is the term used to describe paroxysmal manifestations consistent with lower back or limb cramping, pain, or weakness resulting from vascular compromise or compression of nerve roots of the cauda equina. Occasionally, urinary and fecal incontinence may be the predominant or only clinical manifestation of lumbosacral disease.8 Urinary and fecal incontinence associated with lumbosacral disease most often is caused by denervation of the pelvic and pudendal nerves (S1-S3), resulting in urethral or anal sphincter hypotonia and possibly altered sensation in the perineal region. Because of the relatively heterogeneous and often vague signs associated with lumbosacral disease, this condition is associated with a multitude of differential diagnoses (Table 33-1). The differential diagnosis can be somewhat refined by the presence, type, and severity of any accompanying neurologic deficits relative to the L4-S3/cauda equina region. It is often noticed that geriatric large-breed dogs with historical or clinical evidence of lumbosacral disease often have coincident clinical signs of multifocal myelopathy, usually involving the T3-L3 and L4-S3 spinal cord segments and cauda equina. Multilevel type II thoracolumbar intervertebral disc disease (Figure 33-5) and degenerative myelopathy have been identified repeatedly in dogs with primary clinical complaints referable to lumbosacral disease. Electromyography may demonstrate abnormal spontaneous activity in the muscles of the pelvic limbs, tail, or perineum. Motor and sensory nerve conduction studies may be normal or abnormal, depending on the severity of the disease. F-wave studies, which specifically evaluate motor pathways in the ventral nerve roots and the peripheral axons of motor and mixed nerves, and somatosensory evoked potentials are the most informative and sensitive electrophysiologic studies for the evaluation of cauda equina syndrome.5,37 In human beings with cauda equina compression, abnormalities in somatosensory evoked potentials have been observed before the development of changes in standard electromyographic recordings or peripheral nerve conduction studies. In dogs with lumbosacral disease, the latencies of tibial nerve lumbar somatosensory evoked potentials have been shown to be prolonged when compared with clinically normal controls.37 F-wave latencies would also be anticipated to be prolonged in dogs with compressive radiculopathy. Extensive reviews of electrophysiologic techniques are published elsewhere.5,37 Electrophysiologic studies provide adjunctive diagnostic information that should be considered complementary to clinical and diagnostic imaging examinations. Although abnormal electrophysiologic test results are consistent with a lower motor neuron disorder in animals with lumbosacral disease, they are nonspecific for the cause. In addition, normal electrophysiologic examination results do not conclusively exclude lumbosacral disease as a cause of the observed clinical signs.8 Survey Radiography: Proper radiographic positioning is facilitated by sedation or anesthesia. The primary purpose of survey spinal radiographs in the diagnosis of lumbosacral disease is to exclude vertebral neoplasia, discospondylitis, and vertebral fracture/luxation as causes of the observed clinical signs. Flexed and extended radiographic views of the lumbosacral space have reportedly limited value in the diagnosis of lumbosacral disease,35 as the normal range of motion, vertebral canal diameter, and size of the L7-S1 intervertebral disc space can be variable within breeds and individuals. Radiographic abnormalities involving the lumbosacral region (e.g., spondylosis deformans, narrowing of the L7-S1 disc space, end-plate sclerosis) (Figure 33-6) are common in clinically normal geriatric, large-breed dogs, and are not in and of themselves indicative of cauda equina compression. Conversely, dogs with clinically significant lumbosacral disease may have normal lumbosacral radiographic studies. However, visualization of sacral osteochondrosis or transitional vertebrae on survey radiographs in a patient with clinical evidence of cauda equina dysfunction should increase the index of suspicion that cauda equine compression is present.13,38,39 Linear Tomography: Linear tomography improves radiographic detail within a focal point by blurring anatomic structures superimposed on the selected region of interest. Linear tomography has been demonstrated to be helpful in the detection of lumbosacral lesions15 and is also useful when combined with epidurography. Linear tomography requires specialized equipment and has largely been replaced by cross-sectional imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Venography: Venography involves administration of contrast media into the vertebral venous sinuses, which can be performed via intravenous or transosseous injection techniques.20 Because of the anatomic position of the internal vertebral venous plexus on the floor of the vertebral canal and its course over the dorsolateral aspect of each intervertebral disc, compressive lesions affecting these areas have the potential to provide radiographic evidence of internal vertebral venous plexus compression or displacement. Thus, the position and degree of filling of the internal vertebral venous plexus allow indirect evaluation of possible mass lesions within the vertebral canal. Venography is not used routinely because its interpretation is often confounded by technical injection errors, as well as by inherent normal intraspecies anatomic variation in the arborization patterns of the internal vertebral venous plexus.42

Lumbosacral Spine

Anatomy and Pathophysiology of Lumbosacral Disease

Pathophysiology

Clinical Signs of Lumbosacral Disease

Differential Diagnoses for Lumbosacral Disease/Cauda Equina Syndrome

Diagnosis of Lumbosacral Disease

Electrophysiologic Studies

Radiographic Imaging Studies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Lumbosacral Spine

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue