Chapter 7 Locomotor disorders

Lower limb and digit

Introduction

In dairy cattle, approximately 80% of all lameness originates in the foot, most often in one of the hind feet, arising in the lateral hind claw in the majority of cases. In addition to significant welfare implications, lameness is a major cause of economic loss, as affected animals lose weight rapidly, yields fall and, in protracted cases, fertility is affected. There is also increased culling, and considerable sums of money are spent on treatment and preventive hoof trimming. The severe pain associated with lameness (7.1) is seen as an arched back, front legs forward and apart to take increased weight, and head lowered to bring the center of gravity forward and away from the painful left hind limb. Although accurate figures are not available, lameness in beef cattle has a lower incidence and less economic importance. Many etiological factors are involved, including excessive standing, especially on hard, unyielding tracks and surfaces; rough handling when moving cattle; feet kept continually wet in corrosive slurry; reduced horn growth at calving; and high-concentrate/low-fiber feeds leading to acidosis. All of these factors can precipitate laminitis/coriosis, the consequences of which are abnormal horn growth and hoof wear, softening of the sole horn, dropping of the distal phalanx within the hoof, and a weakening and widening of the white line, all of which predispose to digital lameness.

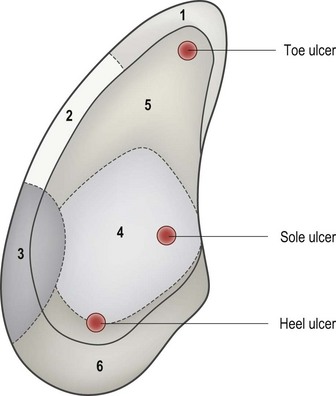

This chapter illustrates the common foot lesions in cattle, namely white line abscess, sole ulcer, interdigital necrobacillosis, interdigital skin hyperplasia, and digital dermatitis. Complications of these primary conditions may produce deeper digital infections, often involving the navicular bursa and, eventually, the pedal (distal interphalangeal) joint. Flexor tendon rupture or coronary band abscessation may result. The final section deals with laminitis/coriosis. Digital lesions due to systemic disease, e.g., foot-and-mouth (12.7) are described in the relevant chapters. The zones of the foot, as defined by the International Ruminant Lameness Symposium, are shown in 7.2, and this nomenclature will be used in the following sections.

Disorders of the sole and axial wall

White line disorders

Definition

the white line is the cemented junction between the sole horn and the hoof wall (zones 1 and 2 in 7.2). It consists of nontubular horn, and as a consequence it is much weaker than the tubular horn of the wall and sole. Disorders of the corium lead to the production of defective white line cement, which predisposes to separation of the sole from the wall and allows entry of small stones, debris, dirt, and infection. Stones in particular act as a wedge, further separating wall from sole. Infection reaching the corium produces pus, the pressure of which causes pain and subsequent lameness. Some cases are thought to arise from an internal sterile inflammation of the corium.

Clinical features

early cases of white line disease are seen as a yellow discoloration (caused by serum) or reddening (caused by hemorrhage) of the white line cement. 7.3 illustrates white line hemorrhage in zone 2 in the right (lateral) claw, hemorrhage at the sole ulcer site (zone 4 left claw), and areas of yellow discoloration in both claws. In more advanced cases (7.4) a fissure develops in the defective white line allowing the penetration of stones and other debris, which then act as a wedge, producing further white line separation. Infection reaching the corium may track either across the sole, or proximally along the laminae, as in 7.5, to discharge at the coronary band. The abaxial white line of the hind lateral claw is most frequently involved, especially zone 3 toward the heel, as it represents a mechanical stress line between the rigid hoof wall and the movement of the flexible heel during locomotion.

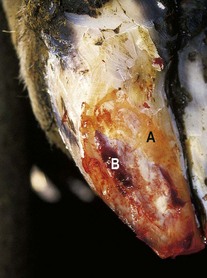

A variety of white line abscesses are seen, depending on both the initial site of penetration of the infection and on the direction of spread. On the left claw of 7.6 light-grayish pus is exuding from the point of entry of infection at the white line near the toe. Pus has tracked under the sole horn, leading to separation of the horn from the underlying corium. Lameness was pronounced. In 7.7 the under-run sole has been removed to expose new sole horn, developing as a layer of creamy-white tissue (A) in the center of the sole and against the edge of the trimmed horn. The hemorrhagic area (B) at the white line is the original point of entry of infection. Progressively deeper penetration of infection occurs in untreated cases. In 7.8, another sole view, the corium has been eroded to expose the tip of the pedal bone (A). This resulted in severe lameness, although the cow eventually made a full recovery. In 7.9 a white line lesion had tracked from the sole dorsally along the laminar corium, then the papillary corium to discharge at the coronary band. Removal of the under-run hoof wall revealed a brown necrotic line. This has permitted drainage. A wooden block has been glued onto the sound claw to rest the affected digit. Although this cow walked soundly within 3 weeks, more than 12 months elapsed before sufficient horn had grown down from the coronet fully to repair the damaged hoof.

Differential diagnosis

punctured (FB) sole, bruised sole, sole ulcer, fracture of distal phalanx, vertical wall fissure.

Axial wall fissure and penetration

Clinical features

most cases of fissure here (7.10) are seen as an impaction of the white line with black debris, often with under-running of adjacent horn. Pain and lameness are a result of the detached axial wall moving on the underlying corium. A foreign body penetrating this region resulted in a localized septic laminitis (7.28) at A, with secondary interdigital swelling and necrosis.

Sole overgrowth

Clinical features

the lateral (left) claw in 7.11 is much larger than the medial claw, and a wedge of overgrown sole horn (A) which has become the major weightbearing surface is growing across towards the medial claw. This wedge predisposes the animal to sole bruising and/or sole ulcers (see 7.13, 7.34). A plantar view is shown in 7.12. The black areas on the heels are early heel erosions (7.67). In front feet sole overgrowth is more commonly seen in the medial claw.

Sole ulcers (“Rusterholz”)

Definition

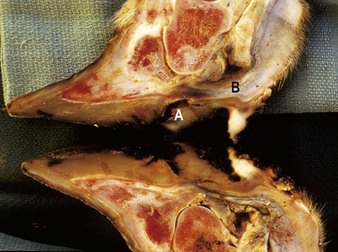

an ulcer is a defect in the horn at zone 4 exposing the underlying corium, and like white line disorders, sole ulceration originates from a defective corium. Heel and toe ulcers are discussed in the next section. Sole ulcers are the most common and are typically found on the axial aspect of the sole in zone 4, beneath the flexor tuberosity of the pedal bone. 7.13 shows two exungulated claws, the left with severe hemorrhage in the corium at the sole (A) which could develop into a sole ulcer, and the right with hemorrhage at the heel ulcer site (B).

Clinical features

in the digit in 7.12 (a plantar view) the wall has been worn down to the level of the sole or lower, and a wedge of sole horn (A) is growing from the axial aspect of the right (lateral) claw towards the left claw. This wedge becomes a major weightbearing surface and transmits excess weight to the sole corium, causing hemorrhage, bruising, and eventually defective horn formation. Note also the heel erosion (B). Another cow (7.14) shows that when such a sole wedge is pared away, a discrete area of sole hemorrhage is revealed in the right (lateral) claw. Note the reddening of the white line in the same claw, indicative of coriosis/laminitis, and also that both claws are overgrown. Further paring and removal of the hemorrhagic horn (7.15) revealed under-run horn and necrosis characteristic of a sole ulcer. Some sole ulcers (7.16) develop a large, protruding mass of granulation tissue. The longitudinal section of another case (7.17) illustrates a mild, chronic ulcer in its characteristic site beneath the flexor tuberosity at the sole–heel junction. The sole horn has been perforated (A) and inflammatory changes have tracked up towards the insertion of the deep flexor tendon. The heel horn is slightly under-run (B) and there is laminitic hemorrhage (coriosis) at the toe (C). Sole ulcers are typically found on the lateral claws of hind feet and, less frequently, on the medial claws of front feet. Often the lateral digits of both hind feet are involved to a different extent. More extensive damage to the corium means ulcers heal more slowly than a white line abscess or an under-run sole (7.7).

Heel ulcers

Definition

heel ulcers occur in the center of the rear sole, at the junction of zones 4 and 6, where the heel horn joins the sole horn, and are shown as areas of hemorrhage in the exungulated right claw in 7.13. Toe ulcers occur at zone 5.

Clinical features

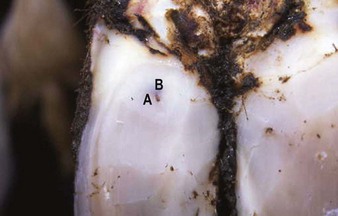

heel ulcers are seen as a small black track (A), seen on the left claw of 7.18 penetrating the sole horn caudally. An area of adjacent dark under-run horn can be seen at B. Removal of overlying horn may lead to the disappearance of small lesions, but in other cases the track leads into a typically deep abscess cavity in the central heel area. In some cases the lesion discharges at the heel, but the depth of the abscess means that this sequel is by no means as common as in sole ulcers or white line disorders. Heel ulcers commonly occur with sole ulcers, although they are more frequently found on the medial claw of hind feet and the lateral claw of fore feet than sole ulcers. In 7.19 a deep heel ulcer (A) is in the center of the right claw and a more superficial sole ulcer (B) is on the axial aspect of the left claw, where there is also extensive white line separation and heel horn erosion. Their etiology is not understood but pinching of the corium between cartilaginous changes in the pedal suspensory apparatus above and the hoof of the sole beneath may be the cause.

Toe ulcers

Clinical features

they may present as larger areas of hemorrhage in zone 5 (7.20) or more commonly simply as a softening of the sole, as in 7.21. Note how the hoof wall has been worn away at the toe, and the presence of early subsolar hemorrhage in 7.21. Frequently seen when heifers and young bulls are introduced into a dairy herd without prior acclimatization to concrete, they appear to be related to trauma and excessive wear. Both front and hind feet may be affected. Excess sole wear is becoming a major problem in some herds, and has led to a suggestion that the frequency, or the extent, of hoof trimming should be reduced.

Toe necrosis (osteomyelitis of distal phalanx)

Definition

abscess at the toe leading to secondary infection of the apex of the pedal (distal phalangeal) bone. Often a sequel to a toe ulcer (7.21). In the UK a high incidence is seen in herds where digital dermatitis is poorly controlled and most cases in dairy cows are infected with treponemes indistinguishable from those causing digital dermatitis.

Clinical features

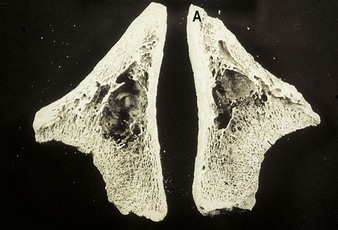

the condition occurs in both dairy cows and in feedlot cattle, and may be associated with excess wear leading to thinning of the horn at the toe. Dairy cows walk with the affected foot forward to relieve pain in the toe, and this typically leads to overgrowth of horn, seen on the medial toe of the right hind foot of 7.22. Note the predisposing poor hygiene underfoot. In another cleaned foot in 7.23 much of the under-run sole and wall at the toe has largely been removed to reveal a black necrotic area tracking up under the dorsal wall. The lesion invariably has a pronounced putrid smell, rarely present in other hoof disorders. The necrotic tip of the pedal bone may be palpated. In a cross-section of another digit (7.24) the apex of the pedal bone has clearly been eroded at A, dry fecal debris is impacted into the residual cavity at the toe, and gray areas of necrotic pedal bone are visible.

Foreign body penetration of the sole

Clinical features

the most common foreign bodies are nails, stones, and cast teeth. In 7.25 a metal staple is firmly impacted in the sole, toward the heel. Unless the foreign body penetrates the sole horn, leading to infection and under-run corium, lameness is relatively mild. In 7.26 a portion of nail has penetrated the sole horn on the axial aspect of the white line, carrying infection into the corium. In 7.27 the superficial under-run horn and adjoining wall have been removed to provide drainage and to expose the new sole (A) developing beneath. In the center (B) is the sensitive corium. Foreign body penetration can also occur near the axial groove (7.28) as the wall horn is thinnest here, leading to secondary interdigital swelling and necrosis, and a septic laminitis. Sole puncture at the toe can cause osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx or pedal bone (7.23, 7.24).

False sole

Clinical features

removal of the under-run sole in 7.27 reveals a thin layer of epidermal horn covering the corium. The detached horn is often called a “false sole.” In another example (7.15) the point of the hoof knife is lifting the false sole. In other cases acute coriosis may lead to a total but temporary cessation of horn production, and the production of a secondary or false sole, with no outward signs of penetration or white line disease.

Vertical fissure (vertical sandcrack)

Clinical features

vertical fissures occur as a result of damage to the superficial periople and underlying coronary band, e.g., following hot, dry weather, or damage to the coronary band from trauma or a digital dermatitis infection. Both claws of the overgrown left forefoot in 7.29 are affected, although the major fissure appears only on the medial claw. Note its irregular course and its origin at the coronary band (A). Note also the section (B), which is slightly loose due to an oblique crack at (C). In 7.30 an extensive, wide, vertical horn crack is shown, in which the laminae are very liable to become exposed, resulting in severe lameness, even though little pus may be present. Another beef cow presented as acutely lame, and extensive paring of a vertical fissure in the front foot eventually led to the release of pus (7.31) and resolution of the lameness. In advanced cases (7.32), where granulation tissue protrudes from the fissure, it is highly probable that an inflamed corium has produced a proliferative osteitis of the extensor process of the pedal bone, and the expanded bone will no longer fit inside the confined space of the hoof.

Management

the fissure should be opened with a hoof knife and under-run or weightbearing horn on each side of the crack removed, as should any hinged portion of horn, thus reducing the movement of the fissure. If granulation tissue is protruding from the fissure, as in 7.32, it is likely that there is also an osteomyelitis of the pedal bone. Digit amputation is then the only treatment. Supplementary biotin has been shown to decrease the prevalence in beef cattle. Control in dairy herds necessitates lowering the incidence of digital dermatitis.

Horizontal fissure (horizontal sandcrack)

Clinical features

in 7.33 both claws are affected: the handheld, cracked, medial hoof wall resulted from a temporary cessation of horn formation 4 months previously, following an abrupt dietary change. Because the length of the anterior wall is greater than the height of the heel, the “thimble” of horn eventually loses its support from the heel, but remains attached at the toe. Lameness results from the pressure of the hinged portion of horn on the underlying laminae, or from exposure of the sensitive laminae when the thimble becomes detached (“broken toe”). In 7.33 a smaller fissure of the lateral claw has been partially trimmed off, without exposing sensitive laminae, to reduce movement of the thimble. Sometimes both claws of all four feet may be affected as a result of a severe systemic insult, e.g., following acute mastitis, foot-and-mouth disease, or acute metritis.

Corkscrew claw

Definition

the claw, usually the lateral claw of both hind legs, is twisted spirally throughout its length.

Clinical features

the lateral claw of the front or the hind feet can be affected by this partially heritable growth defect. The overgrown lateral toe in 7.34 deviates upward, and in the same digit, the abaxial wall curls under the sole (7.35), inevitably altering the weightbearing surfaces. The axial sole overgrowth (A) consequently becomes a major weightbearing surface and lameness can result from sole ulcers and/or pedal bone compression (see also 7.11). In the pedal bone specimen in 7.36, osteolysis secondary to corkscrew claw compression is seen near the toe, at A. The left pedal bone and the cavitation are normal. 7.35 also shows early bilateral heel erosion (see also 7.67), and cavitation of the sole of the medial claw due to impaction by debris.

Complications of digital hoof disorders

Abscess at the coronary band

Infection originating at the white line has passed proximally under the hoof wall to the coronet in 7.38, where it has penetrated the deeper tissues of the collateral digital ligaments to produce a septic cellulitis, with pronounced swelling around the coronary band. As well as highlighting the overgrowth of the sole horn, this chronic lesion shows that the horn wall is detached from the coronet beneath the abscess. The affected toe has deviated dorsally, suggesting partial rupture of the flexor tendon, and leading to relative horn overgrowth from lack of wear.

Abscess at heel (retroarticular abscess; septic navicular bursitis)

Clinical features

severe lameness and swelling of the heel area and coronary band, which may extend dorsally toward the fetlock and above. In a longitudinal section of a claw (7.39), purulent infection can be seen in the digital cushion (A) adjacent to the navicular bone, the deep digital flexor tendon (B), and adjacent to the pedal joint (C). This is sometimes referred to as a retroarticular abscess, and needs surgical drainage. Similarly 7.40 shows heel enlargement and a purulent exudate, probably from an infected navicular bursa or a retroarticular abscess discharging through the original ulcer site (A). A wooden block has been applied to the sound claw. Flexor tendon rupture (7.42) may result from complicated cases (see below).

Rupture of the deep flexor tendon

Clinical features

complications from severe white line abscess, sole ulcer, or, as in 7.41, retroarticular heel abscess can lead to infection and the subsequent rupture of the deep flexor tendon. In 7.41 the coronary band is severely distorted, the heel is swollen, and the toe deviates upward (plantigrade), leading to continual overgrowth and lack of wear of the affected claw. A longitudinal section of a septic digit (7.42) reveals the site of an ulcer that perforated the sole horn (A), and the point of rupture of the deep flexor tendon (B). Note the horn overgrowth at the toe. At this stage the joint is not affected and recovery is possible with prompt treatment.

Septic pedal arthritis (distal interphalangeal sepsis)

Clinical features

pedal arthritis typically results from a severe or neglected white line abscess, sole ulcer or interdigital necrobacillosis infection and produces severe, often non-weightbearing, lameness. Note the marked unilateral enlargement of the left heel in 7.43, with inflammation tracking up toward the fetlock and causing distortion of the claw. The navicular bursa and pedal joint are also infected, producing a septic pedal arthritis. Gross enlargement can result in lifting of digital sole and heel horn, especially at the heel and toward the interdigital space. The Hereford cow in 7.44 had been lame for 8 weeks. The affected lateral claw is grossly enlarged and inflamed, there is swelling of the coronet and separation of horn at the coronary band (A), and granulation tissue protrudes into the interdigital space at the point where pus discharges from the infected joint. Despite a less severe degree of swelling in the more chronic case in 7.45, the hoof on the affected lateral claw is being avulsed by pressure and necrosis from a septic coronitis.

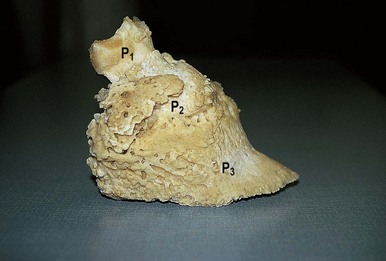

Long-standing digital infections may lead to an osteitis and a proliferation of new bone, as in 7.46, which is a boiled-out specimen of a chronically infected sole ulcer in a Holstein cow. A deep cavity was present at the ulcer site, with extensive new bone proliferation in the navicular bone, digital cushion, and coronary areas. When P1, P2, and P3 became ankylosed, the severity of lameness decreased. In 7.47, which is a sagittal section following digital amputation, necrosis in the navicular bone has extended to cause severe sepsis in the distal joint. Infection at the coronary band (B) has produced swelling above the coronet.

Disorders of the digital skin and heels

Interdigital necrobacillosis (phlegmona interdigitalis, “foul”, “footrot”)

Clinical features

early cases have an obvious lameness and show a symmetrical, bilateral, hyperemic swelling of the heel bulbs that may extend to the accessory digits. At this stage, the interdigital skin is swollen but intact, and the claws appear to be pushed apart when the animal stands. After 24–48 hours the interdigital skin splits (7.48) (some sloughed epidermis has been removed), and in later cases the dermis is exposed (7.49). More extensive exposure of the dermis is often seen (7.50), with development of granulation tissue. A foul-smelling, caseous exudate may be present (7.51). 7.52 is a dorsal view of a neglected case after cleansing, with sloughed necrotic debris in the interdigital space. The depth of the necrotic process has caused proliferation of granulation tissue. Early separation of the axial wall of the left claw (A) and swelling of the coronet suggest early inflammatory changes in the pedal joint. The horizontal groove (B) distal to the coronary band indicates that the problem has existed for about 1 month.

A peracute form of interdigital necrobacillosis exists known as “super foul” (7.53), where severe necrosis extends from the interdigital cleft onto the heel skin. The dermal necrosis is savage in onset and there may be joint involvement within 48 hours of initial clinical signs. The same causative organisms are involved, although the antibiotic sensitivity pattern may differ. Prompt and aggressive therapy is vital.

Differential diagnosis

interdigital dermatitis (7.65), interdigital foreign body (7.69), digital dermatitis (7.57–7.59).

Interdigital skin hyperplasia (fibroma, “corn”)

Definition

hyperplasia in the interdigital space develops from skin folds adjacent to the axial hoof wall, as shown in 7.54.

Clinical features

the lesion, which in some cases may be inherited and is then usually bilateral, is a problem in heavier breeds of beef and dairy cows as well as mature beef bulls. Lameness is produced either when the claws pinch the interdigital skin during walking, or following secondary (necrobacillary) infection in areas of pressure necrosis (7.55) and commonly as a result of secondary infection with digital dermatitis. Note the superficial but severe slough of necrotic material. In a few cases hyperplasia is restricted more to the dorsal interdigital space (7.56), when lameness is less likely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree