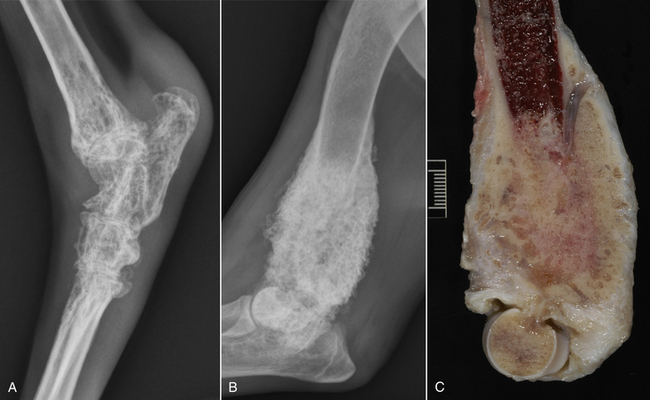

Chapter 63 Coccidioides spp. are dimorphic, soil-borne fungi that exist in the environment as a mycelium and in tissues (at 37°C) as peculiar structures known as spherules. The mycelium consists of chains of haploid, multinucleated, barrel-shaped arthroconidia (or arthrospores) that alternate with smaller, thin-walled, nonviable cells. The arthroconidia remain viable in the soil for long periods. They ultimately fragment from each other and are subsequently aerosolized and inhaled by animal hosts (Figure 63-1). This can be followed by the development of coccidioidomycosis, a localized pulmonary disease or a serious multisystemic disease if dissemination occurs in the face of inadequate immune responses. FIGURE 63-1 Life cycle of Coccidioides spp. Hyphae fragment into arthroconidia, which are inhaled and form spherules in tissues. The spherules rupture and release endospores, which form new spherules. In some dogs, the organism disseminates from the lungs to a variety of other tissues, but especially local lymph nodes, bone, skin, the pericardium, the eye, and the central nervous system. In the environment, Coccidioides spp. are distributed in the lower Sonoran life zone, regions characterized by semiarid to arid soils, low elevations above sea level, and hot summers. Worldwide, Coccidioides spp. are found in the southwestern United States, Mexico, and parts of Central and South America, specifically Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Venezuela, northeastern Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia (Figure 63-2). In the southwestern United States, highly endemic regions are the south-central valley of California, especially Bakersfield (“valley fever”) and Arizona, especially Tucson and Phoenix.2 Infections also occur in non-endemic regions in dogs and humans that have a travel history to endemic regions. FIGURE 63-2 Geographic distribution of Coccidioides spp. worldwide. The inset shows the distribution of Coccidioides species in the southwestern United States. Two species of Coccidioides have been identified, C. posadasii and C. immitis. These appear to cause similar clinical manifestations and have similar antifungal drug susceptibilities, but further studies are required.3 The geographic range of C. immitis is largely limited to the central valley of California, whereas C. posadasii is found elsewhere.4 However, there may be some overlap in the distribution of these organisms. Infection of animals and humans with Coccidioides spp. often follows a cycle of moist conditions (required for growth of the organism in the soil), a dry period, then soil disruption, such as may occur with heavy rainfall, earthquakes, dust storms, prolonged droughts, or construction.5–7 Dogs of any breed, age, or sex may be affected, although large-breed, young adult dogs predominate in case series.8,9 In dogs seen at the University of California Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, boxers, poodles, pointers, Labrador and golden retrievers, German shepherds, Australian shepherds, Dalmatians, Scottish terriers, dachshunds, and beagles are overrepresented when compared with the hospital patient population.10 Risk factors for infection in dogs from Arizona include being housed outdoors during the day rather than indoors, roaming areas more than 1 acre, and walking in the desert.11 Latent infections may also occur in dogs, and these can reactivate after treatment with immunosuppressive drugs, such as corticosteroids and chemotherapeutic agents, including after previous recovery from coccidioidomycosis. Although not as prevalent as in dogs, coccidioidomycosis also occurs in cats.12 In a study of 48 cats from Arizona, cats ranged in age from 1 to 15 years (median, 5 years) and there was no obvious sex or breed predisposition.12 One cat was infected with FIV, and all cats tested were FeLV negative. Interestingly, a search of the author’s hospital and pathology database from 1990 to 2012 revealed not a single cat with coccidioidomycosis, which might suggest cats are less susceptible to C. immitis infection than to C. posadasii infection. The clinical signs of coccidioidomycosis depend on factors such as the infectious dose and the immune status of the host. Arthroconidia are inhaled and are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. They then enlarge into a spherule, which measures 8 to 100 µm in diameter. Hundreds of endospores then develop within the spherule, which are released when the mature spherule ruptures. These attract neutrophils, which leads to a pyogranulomatous inflammatory response. Each released endospore that escapes immune destruction then enlarges into a new spherule, and the cycle continues. Endospores can revert to mycelial growth when removed from the site of infection. In hosts that are unable to mount an effective immune response, endospores disseminate by lymphatics to tracheobronchial lymph nodes and hematogenously to a variety of body sites. Inoculation coccidioidomycosis can rarely occur, and generally results in lesions that are localized to the site of the wound. In one report, it followed removal of a foxtail from a wound.13 Most infections in endemic areas are subclinical.14 Development of clinical signs often follows a subacute to chronic course, with variable and often mild systemic signs such as intermittent fever, lethargy, inappetence, and weight loss.8,15 Many dogs otherwise appear healthy, with occasional periods of inappetence.8 Clinical signs may be present for days to years before veterinary attention is sought.9 Signs of respiratory tract involvement include a harsh cough, increased respiratory effort, tachypnea and/or exercise intolerance.9,15 Cough may be chronic and is sometimes associated with gagging or retching; occasionally it results from bronchial compression by enlarged tracheobronchial lymph nodes. Rarely, diffuse pneumonia follows a fulminant course, with signs that resemble acute bacterial pneumonia or septic shock, as reported in immunocompromised human patients.2 A smaller percentage of infected dogs develop disseminated infections. Sites of dissemination often include osteoarticular sites, the central nervous system (CNS), skin, peripheral lymph nodes, eyes, testes, prostate, and the pericardium.9,10 Rarely, sites such as the liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, or urinary system are affected.8 Sometimes dissemination to only one anatomic site is evident; in other dogs multiple sites are involved. A history of respiratory signs may be absent.8 Bone involvement may manifest as lameness and/or one or more firm swellings associated with the appendicular or axial skeleton. Dogs with skin involvement may have subcutaneous masses ulcerated skin lesions that drain serosanguineous fluid (Figure 63-3).8 Skin lesions may overlie sites of osteomyelitis. Neurologic signs result from meningoencephalitis and include obtundation, blindness, nystagmus, absent menace reflexes, diminished gag responses, ataxia, abnormal placing reactions, pacing, circling, cervical pain, tetraparesis, and seizures.9,16,17 Ocular manifestations of coccidioidomycosis include chorioretinitis, uveitis, optic neuritis, and endophthalmitis.9,18,19 Involvement of abdominal organs such as the liver and gastrointestinal tract can lead to inappetence, vomiting, and/or diarrhea.8 Pericarditis may lead to signs of right-sided cardiac failure, with ascites and pleural effusion.8 FIGURE 63-3 Draining skin lesion on the left elbow of a 5-year-old shepherd mix with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Radiography revealed a mixed productive and destructive lesion of the distal humerus and proximal ulna. Productive lesions of the sixth and seventh ribs were also present. Arthrocentesis revealed suppurative inflammation with no growth on culture. Diagnosis was ultimately made by biopsy of the synovium and serology. The Coccidioides titer was 1:64. Fever is present in up to two thirds of dogs with coccidioidomycosis (range, 103°F to 106°F) on physical examination. Other common findings in dogs are lethargy, weakness, thin body condition or profound muscle atrophy, tachypnea, increased respiratory effort, inducible or spontaneous cough, and/or increased lung sounds.9 Lameness and firm, often painful bony swellings with associated muscle atrophy may be present in dogs with osteomyelitis. Less often, focal or (very rarely) generalized peripheral lymphadenomegaly, subcutaneous masses or draining skin lesions, or swollen joints are present. Dogs with pericardial coccidioidomycosis may have abdominal distention with a palpable fluid wave, tachycardia, tachypnea, jugular pulses, muffled breath and heart sounds due to pleural effusion, mucosal pallor, prolonged capillary refill time, and weak pulses.20 Neurologic signs, when present, include obtundation, apparent blindness, ataxia, nystagmus, spinal pain, circling, and tetraparesis. The most common ocular abnormality is uveitis, but keratitis, conjunctivitis, granulomatous chorioretinitis, optic neuritis, retinal detachment, and endophthalmitis with secondary glaucoma have also been described.9,18,19 Of 48 cats with coccidioidomycosis, fever was present in 31%. Skin lesions were present in more than 50% of 48 affected cats and included draining skin lesions, subcutaneous granulomas, and abscesses.12 Tachypnea or increased respiratory effort was present in 25% of affected cats, and lameness in fewer than 20% of cats. Ocular abnormalities were present in 13% of cats. Conjunctival masses, periorbital swellings, chorioretinitis, retinal detachment, endophthalmitis, and/or anterior uveitis have been described.21,22 A small percentage of cats have neurologic signs such as hyperesthesia, posterior paresis, seizures, and ataxia. Dissemination to abdominal organs such as the spleen can occur.23 Coccidioidomycosis is usually suspected based on a history of travel to or residence in an endemic region, and consistent clinical signs and radiographic findings. Because the disease is not prevalent in some endemic regions (such as coastal southern California), early diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion in these regions. The diagnosis can be confirmed with cytologic examination of aspirates or body fluids, serologic assays that detect antibodies to Coccidioides spp., histopathology, and/or fungal culture (Table 63-1). CBC findings in dogs with coccidioidomycosis are nonspecific and resemble those of other deep mycoses. Most affected dogs have mild, normocytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anemia and mild leukocytosis. Leukocytosis results from a neutrophilia, occasionally with a left shift and evidence of neutrophil toxicity.9,20 A monocytosis and lymphopenia may also be present, but in contrast to human infections, eosinophilia is not typically present. Almost all dogs with coccidioidomycosis have hypoalbuminemia, and approximately half of affected dogs and cats have hyperglobulinemia (up to 7.8 mg/dL in one study).9,12 Hypoalbuminemia is usually mild to moderate, but rarely may be more severe (<1.5 g/dL). Uncommonly, mild hypercalcemia is present. Increased activity of serum ALP may be present in some dogs, possibly as a result of bone involvement. The urinalysis is often normal, but significant proteinuria (urine protein-to-creatinine ratios as high as 9.5, reference range <1) has been reported in some dogs with coccidioidomycosis.9 It is not clear whether proteinuria of this magnitude results from glomerulonephritis secondary to chronic immune stimulation or another comorbidity. CSF analysis in dogs with CNS coccidioidomycosis usually reveals an increase in protein concentration (generally <300 mg/dL, reference range <25 mg/dL) and a mild to moderate increase in the nucleated cell count (usually <50 cells/µL, reference range <2 cells/µL).9 The differential cell count may show mixed, predominantly lymphocytic, mixed mononuclear, or neutrophilic pleocytosis. Organisms are generally not observed. Thoracic radiographs in dogs with disseminated coccidioidomycosis are often unremarkable. The most common radiographic finding in dogs with pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is mild to severe hilar lymphadenomegaly (Figure 63-4, A), which was present in 10 of 19 dogs with coccidioidomycosis from California.9 Hilar lymphadenopathy can also be present in affected cats.12 Although hilar lymphadenopathy can be the only finding, most dogs with hilar lymphadenopathy also have pulmonary infiltrates, which are usually mild to moderate and interstitial. Nodular interstitial, interstitial-alveolar, bronchointerstitial infiltrates, and/or sternal lymphadenomegaly can also be present (Figure 63-4, B and C).9,15 Dogs with pericarditis can have cardiomegaly and pleural effusion, with hepatomegaly and decreased abdominal detail.20 FIGURE 63-4 Thoracic radiographic patterns in coccidioidomycosis. A, Lateral thoracic radiograph from a 7-year-old intact male English pointer that shows several tracheobronchial lymphadenomegaly and focal pulmonary infiltrates. B, Lateral thoracic radiograph from a 3-year-old intact female Rottweiler with cough, anorexia, and respiratory distress. There are diffuse nodular and peribronchial infiltrates throughout the pulmonary parenchyma and possible hilar lymphadenopathy. Necropsy revealed necrogranulomatous interstitial pneumonia with intralesional spherules. The spleen, liver, and kidney were also involved. C, Dorsoventral thoracic radiograph from a 2-year-old female spayed Labrador retriever with cough and inappetence. There is an alveolar pattern in the left cranial lung lobe. Radiographs of affected bones in both dogs and cats with Coccidioides osteomyelitis reveal local periosteal proliferation as well as osteolysis and soft tissue swelling. Lesions can resemble osteosarcomas (Figure 63-5).8,12 FIGURE 63-5 Osteomyelitis caused by Coccidioides spp. A, Left tarsus of a 4-year-old female spayed Dalmatian that was evaluated for signs of right-sided congestive heart failure due to pericarditis. Severe osteolysis is present. B, Right humerus of a 4-year-old female spayed shepherd mix. There is a mixed productive and lytic lesion of the distal diaphysis of the right humerus. C, Lesion in (B) at necropsy. (Courtesy University of California, Davis, Veterinary Anatomic Pathology Service.)

Coccidioidomycosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Clinical Features

Physical Examination Findings

Diagnosis

Laboratory Abnormalities

Serum Biochemical Tests

Urinalysis

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

Diagnostic Imaging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Coccidioidomycosis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue