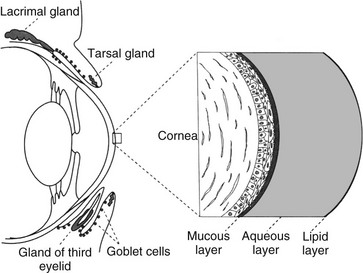

The PTF is a mixture of lipid, aqueous, and mucin components, with regional variation in the concentration of these components (Web Figure 79-1). The exact thickness of the feline PTF has yet to be established; past measurements of the PTF have estimated its thickness to be 7 to 10 µm, with aqueous layer being most abundant. However, research into the human PTF has yielded variable results, including the suggestion of a much thicker tear film consisting mainly of mucin.

The lipid layer is composed of a mixture of polar and nonpolar lipids that tends to be more concentrated at the outermost portion of the PTF. The feline lipid layer resembles that of humans, being thinner than that in dogs. The meibomian or tarsal glands, located within the eyelids, are the main source of PTF lipids. Tear film lipid, or meibum, exists as a liquid at body temperature, which allows it to be spread across the surface of the PTF with eyelid movement. This layer minimizes evaporation of the PTF between blinks and decreases the surface tension of the tear film, thereby maintaining tear film stability and a smooth, optically clear surface.

The mucin component is concentrated at the innermost aspect of the PTF. The majority of ocular mucins are secreted by the conjunctival goblet cells, with lesser contributions from the epithelial cells of the conjunctiva and cornea as well as the orbital lacrimal gland. Although goblet cells are located throughout the conjunctiva, they are particularly concentrated within the ventromedial conjunctival fornices. Mucin plays an integral role in maintaining tear film stability by decreasing the surface tension of the tear film; it also binds contaminants such as particulate matter and bacteria, and aids in maintaining an optically smooth surface by filling irregularities of the corneal epithelial surface. Because of its viscous nature, mucin also helps the hydrophilic tear film adhere to the hydrophobic corneal epithelium.

Although tears are responsible for both conjunctival and corneal surface health, the cornea’s lack of blood supply renders the effects of tear deficiency more notable there than on the conjunctiva; nevertheless, conjunctival effects also remain important. Any alteration of either the lipid or mucin layer is referred to as a qualitative tear film abnormality, whereas a deficiency of the aqueous component is termed a quantitative tear film abnormality.

![]()