Chapter 16 Cardiac murmurs

valvular regurgitation and insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

One of the commonest cardiological dilemmas that faces the equine practitioner is the assessment of a horse, otherwise apparently healthy, in which a murmur is detected. This situation arises frequently in the context of examinations for suitability for purchase. Equally, in horses presented for investigation of poor performance, a murmur may have uncertain significance. The characteristic auscultatory features of equine cardiac murmurs are described in detail in Chapter 8. The investigation and management of horses with congenital cardiac disease (see Chapter 15), and infective endocarditis (see Chapter 17) and heart failure (see Chapter 19), are described elsewhere in this book. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the investigation and management of cardiac murmurs in adult horses which are otherwise asymptomatic or have poor performance, the setting in which cardiac murmurs are most frequently encountered.

PATHOLOGICAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL REGURGITATION

Valvular regurgitation is an important cause of murmurs in horses, second only to physiological flow murmurs in prevalence, and it occurs both in the presence and absence of valvular pathology.1–6 Valvular lesions can be congenital, degenerative, inflammatory or idiopathic in nature1,5,7–13 (see Chapter 4). The term valvular insufficiency can be defined as valvular regurgitation that is sufficiently severe to lead to some degree of haemodynamic changes and it is typically associated with some form of valvular pathology. However, it is important to recognize that valvular regurgitation can occur at structurally normal valves and in this setting it is described as physiological regurgitation. Furthermore, valvular regurgitation can be detected with Doppler echocardiography in many horses without murmurs.2,4,6

Valves are not inert structures; rather their tone and stiffness can be modified dynamically, under the influence of a variety of vasoactive mediators, just as is the case with blood vessels14 (see Chapter 4). The factors that influence physiological regurgitation are not yet well understood and may involve not only neuroendocrine factors but also changes in the geometry of the ventricles that are part of cardiac adaptation to exercise and training. Physiological regurgitation is more common in human and canine athletes than sedentary individuals and it is well established that atrioventricular valvular regurgitation, both with and without murmurs, becomes more prevalent and more severe as Thoroughbred horses progress through training.6,15 There is a higher prevalence of physiological regurgitation in racehorses trained for steeplechasing compared to flat races, suggesting that the cardiac adaptations that relate to the most intense, sustained exercise may be important in the development of physiological regurgitation6 (see Chapter 3). There is no relationship between the presence and absence of physiological regurgitation and racing performance,6,16 providing further evidence that this is a physiological rather than pathological phenomenon. The task of the clinician when called upon to examine a horse with a regurgitant murmur is first to distinguish between physiological and pathological regurgitation and then if pathological regurgitation is present, to determine whether it is of sufficient severity that it is likely to be affecting the horse’s well-being and exercise capacity.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT OF HORSES WITH MURMURS

Clinical assessment of a horse with a murmur due to valvular regurgitation involves:

• History taking, with an emphasis on identifying exercise intolerance, fatigue, weight loss and other features that might indicate cardiac disease or dysfunction.

• General physical examination.

• Auscultation to characterize and localize the valve involved.

• Echocardiography to confirm valvular regurgitation and estimate its severity.

• Electrocardiography to investigate concurrent dysrhythmias.

In horses with valvular regurgitation, M-mode, two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography (see Chapter 9) are used to3,5,17–26:

• Identify specific forms of valvular pathology.

• Semiquantitate the severity of regurgitation.

• Document the size and shape of the cardiac chambers and great vessels.

The criteria recommended for the evaluation of severity of valvular regurgitation in horses include the presence and specific type of echocardiographically demonstrable valvular lesions, the degree of atrial and ventricular volume overload, and the timing of and area occupied by the regurgitant jet mapped by pulsed or colour flow Doppler echocardiography.21 The chronicity of lesions can sometimes be inferred by the correlation of the jet size and the chamber enlargement and in acute, severe disease, a large jet may not necessarily be associated with chamber enlargement because this takes time to develop. The rate of progression can be assessed most accurately by repeated echocardiographic examinations.21 Conventional, radiotelemetric and ambulatory electrocardiography can be useful to detect concurrent dysrhythmias (see Chapter 10). When the information generated with these techniques is considered in the light of the presenting signs and the owner’s expectations for the horse, it is usually possible for the clinician to provide an accurate prognosis and advise the horse’s owner on suitable management and the appropriate exercise level for the horse. Although in the following discussion, each valve is considered in turn, it is important for the clinician to remember that there may be valvular regurgitation in more than one valve and the clinical impact of multiple regurgitations may be additive.

AORTIC VALVULAR REGURGITATION AND INSUFFICIENCY( AR)

AR)

Prevalence

Estimates of the prevalence of aortic regurgitation (AR) have varied depending on the study populations and on the techniques used to define the diagnosis but AR appears to increase in prevalence with age and small riding breeds (i.e. Thoroughbred and Arab or crosses thereof) are at increased risk of having AR compared to small ponies.27 The prevalence of audible murmurs of AR was 8.7% in cases at a referral hospital,28 2.2% in a mixed working population,29 5.5% in a mixed population with a median age of 14 years, many of whom were retired,27 7% in steeplechasers in the UK6 but 0–1% in various categories of younger Thoroughbreds competing on the flat.6 The true prevalence of AR is probably much greater, and with Doppler echocardiography, physiological AR can often be identified in horses with no murmurs.2,4,6

Pathogenesis

The aortic valve is the commonest site for valvular pathology, particularly in the middle-aged and older horse.1,8 Degenerative lesions consisting of nodular or, less commonly, generalized fibrous thickenings are seen most often on the left coronary cusp, although any or all of the three cusps may be affected.1,8,9,22 Valvular prolapse is a precursor to valvular disease in dogs30 but this association has not been investigated in horses. The term aortic valvular prolapse refers to abnormal movement of the valve cusps during diastole such that they flop downwards into the ventricle. It is detected echocardiographically and must be visible in at least two perpendicular planes to confirm its presence. It can be seen in both the presence and absence of valvular pathology and in the presence or absence of AR.4 It is a dynamic process that can be induced by application of a twitch and is extremely common in fit Thoroughbred racehorses compared to other breeds and those in lighter work.31 It remains to be established whether aortic valvular prolapse is a risk factor for valvular disease later in life. (![]() AR)

AR)

Infective endocarditis can affect the aortic valve12,22,32,33 (see Chapter 17). All forms of congenital valvular lesions are extremely uncommon in isolation but congenital malformations have been reported in the aortic valve.34,35 AR can accompany ventricular septal defects, when the presence of the defect immediately beneath the aortic root leads to instability and, in some cases, rupture of the aortic valve22,36 (see Chapter 15). Fenestrations of the free edges of the cusps are a common feature of both the aortic and pulmonary valves in the horse and have been observed in both equine fetuses and mature animals.7 Provided these are not extremely extensive, they are not thought to have any clinical significance, representing a normal variant rather than a pathological entity.7

Clinical findings( AR, IE)

AR, IE)

The murmur of AR is typically pan, holo- or early diastolic, decrescendo and has its point of maximal intensity over the aortic valve in the left fifth intercostal space and radiates variable distances ventrally towards the heart base (see Chapter 8). It may be musical in quality, and in some horses it has a bizarre “creaking” quality, which may be due to vibrations of cardiac structures, such as the mitral valve and the ventricular septum, rather than turbulent blood flow itself.28

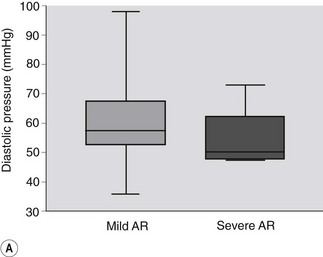

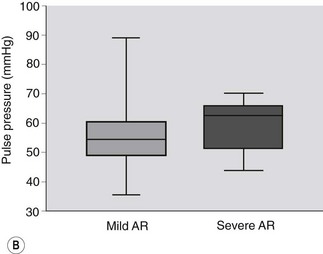

The clinical findings that warrant further investigation in horses in which a murmur of AR is detected are summarized in Table 16.1. Horses with more severe AR are likely to have loud diastolic murmurs, multiple heart murmurs and hyperkinetic pulses.37 The best clinical guide to severity of AR is the quality of the arterial pulses, rather than the grade of the murmur. It can also be useful to measure noninvasive arterial pressure, which provides a useful guide to severity: horses with severe AR have a diastolic arterial pressure below 50 mmHg and a pulse pressure (i.e. systolic – diastolic) of greater than 60 mmHg compared to horses with mild AR37 (Fig. 16.1). As the insufficiency becomes more severe, increases in resting heart rate may also be observed.

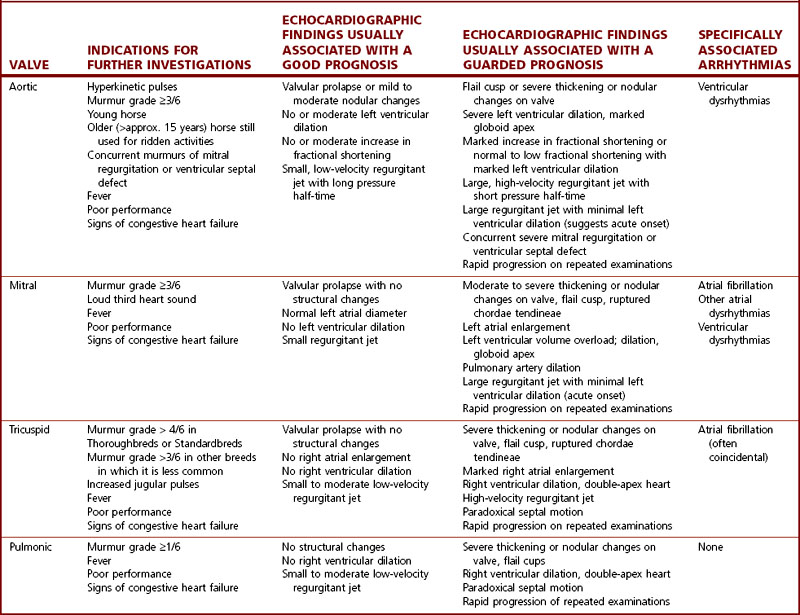

Table 16.1 Guidelines for interpreting the clinical significance of valvular regurgitation in horses presented for investigation of murmurs

Echocardiography( ET, IE, VSD, AF)

ET, IE, VSD, AF)

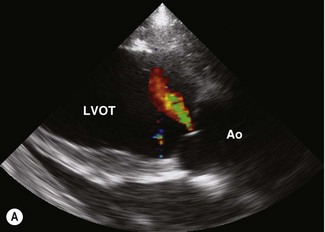

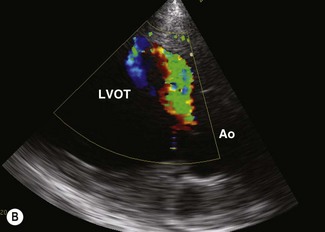

Colour flow Doppler echocardiography can readily demonstrate the area occupied by the jet of AR (Fig. 16.2). Unfortunately, measurements of the maximum width, length and width at the base are not very repeatable or reproducible and changes over time must be in excess of 20% in order to document genuine progression of the AR. Doppler echocardiography can also be used to assess pressure gradients that arise as a result of AR. In human beings, the maximal velocity and pressure half-time of the regurgitant jet can be related to the severity of ventricular volume overload. In one study, horses with AR on Doppler echocardiography had significantly larger and faster regurgitant jets if a cardiac murmur was present, suggesting that these parameters do reflect severity to some extent.26 However, critical prospective studies have not addressed the sensitivity, specificity and reliability of these variables in the horse.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree