cellular and pericellular space into the circulation to support central venous pressure. See Chapter 8 for further details of its use. It must be administered intravenously or intraosseously.

Protein amino acid/B vitamin supplements

Protein and vitamin supplements are useful for nutritional support (e.g. Duphalyte® at 1 mL/kg per day). These supplements are particularly good in cases where the patient is malnourished or has been suffering from a protein-losing enteropathy or nephropathy. It is also a useful supplement for patients with hepatic disease or severe exudative skin diseases.

Colloidal fluids

These are of use in small mammals which may be given an intravenous bolus. They are used when a serious loss of blood occurs in order to support central blood pressure. This may be a temporary measure while a blood donor is selected, or, if none is available, the only means of attempting to support such a patient.

Blood transfusions

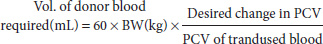

If the packed cell volume (PCV) starts to drop below 20%, blood transfusions may be required. They must be same species-to-species transfers (i.e. rat to rat, guinea pig to guinea pig). The donor may have 1% body weight in blood removed, assuming it is healthy. The sample is best taken directly into a pre-heparinised syringe, or using citrate acid dextrose at 1 mL of anticoagulant to 5–6 mL of blood, and immediately transfers it in bolus fashion to the donor. The use of intravenous catheters is advised, as administration should be slow, giving 1 mL over a period of 5–6 minutes. Therefore sedation, or good restraint, is required. Very little information is currently available about crossmatching blood groups of small mammals, although ferrets, it seems, do not have detectable groups. Intraosseous donations may be made if vascular access is not possible. Calculations for volumes are based on those available for cats, that is

where BW is body weight of the recipient in kilograms.

Oral fluids and electrolytes

Oral fluids may be used in small mammal practice for those patients experiencing mild dehydration, and for home administration. The most useful products contain pro/prebiotics which aid the return to normal digestive function.

Calculation of fluid requirements

Fluid within food is difficult to take into consideration when calculating fluid needed, and therefore it is safer to assume that the debilitated small mammal will not be eating enough for it to matter. Once it is appreciated that maintenance for most small mammals is double that required for the average cat or dog, then deficits may be calculated in the same manner. Assume that 1% dehydration equates with needing to supply 10 mL/kg fluid replacement, in addition to maintenance requirements.

Then estimate the percentage of dehydration of the patient as follows:

- 3–5% dehydrated – increased thirst, slight lethargy, tacky mucous membranes

- 7–10% dehydrated – increased thirst, anorexia, dullness, tenting of the skin and slow return to normal, dry mucous membranes, dull corneas

- 10–15% dehydrated – dull to comatose, skin remains tented after pinching, desiccating mucous membranes.

Alternatively, if a blood sample may be obtained, a 1% increase in PCV, associated with an increase in total proteins, may be assumed to equate to 10 mL/kg fluid deficit (see Table 6.2).

Table 6.2 Comparison of normal PCV and total proteins for selected small mammals.

| Species | PCV range (L/L) | Total protein (g/L) |

| Ferret | 0.44–0.60 | 51–74 |

| Rabbit | 0.36–0.48 | 54–75 |

| Guinea pig | 0.37–0.48 | 46–62 |

| Chinchilla | 0.32–0.46 | 50–60 |

| Rat | 0.36–0.48 | 56–76 |

| Mouse | 0.39–0.49 | 35–72 |

| Gerbil | 0.43–0.49 | 43–85 |

| Hamstera | 0.36–0.55 | 45–75 |

| Sugar glider | 0.45–0.53 | 51–61 |

| Virginia opossum | 0.34–0.47 | 56–78 |

| a The range given for hamsters is an average of Syrian and Russian hamster values. | ||

These deficits may be large and difficult to replenish rapidly. Indeed, it may be dangerous to overload the patient’s system with these fluid levels all in one go. Therefore, the following protocol is worth following to ensure fluid overload, renal shutdown and pulmonary oedema are avoided:

- Day 1: Maintenance fluid levels +50% of calculated dehydration factor

- Day 2: Maintenance fluid levels +50% of calculated dehydration factor

- Day 3: Maintenance fluid levels

If the dehydration levels are so severe that volumes are still too large to give at any one time, it may be necessary to take 72 hours rather than 48 hours to replace the calculated deficit.

In addition, in those species such as ferrets, which can vomit, the fluid lost in vomitus expelled should be considered, assuming 2 mL/kg per vomit.

In other species such as the small herbivores, where diarrhoea only is the norm, it is much more difficult to make estimations, although fluid losses may approach 100–150 mL/kg per day.

Equipment for fluid administration

Catheters

The blood vessels available for intravenous medication are often 30–50% smaller than their cat and dog counterparts. Small paediatric butterfly catheters may be used. It is advisable to flush with heparinised saline, prior to use, to prevent clotting. Catheters of 25–27 gauge are recommended and will cope with venous access for rabbits, guinea pigs, chinchillas and ferrets. Occasionally a 28- or 29-gauge catheter may be needed to catheterise a lateral tail vein in a rat or mouse, although 27-gauge catheters often suffice.

Hypodermic or spinal needles

Hypodermic and spinal needles are useful for the administration of intraosseous, intraperitoneal and subcutaneous fluids. The intraosseous route may be the only method of giving central venous support in very small patients, or patients where vascular collapse is occurring. The proximal femur, tibia or humerus may be used. Entry can be gained by using hypodermic or spinal needles. Spinal needles are preferable because they have a central stylet to prevent clogging of the needle lumen with bone fragments after insertion. Spinal needles of 23–25 gauge are usually sufficient.

Hypodermic needles may be used for the same purpose, although the risks of blockage are higher. Hypodermic needles may also be used for the administration of intraperitoneal and subcutaneous fluids. Generally, 23–25 gauge hypodermic needles are sufficient for the task.

Nasogastric tubes

Nasogastric tubes are often used in small mammals to provide nutritional support in as stress-free a manner as possible. They are useful as a route for fluid administration. It should be noted though that in severely dehydrated individuals, there is no way that all of the fluid deficits may be replaced via this route alone. This is due to the limited fluid capacity of the stomach of these species, as well as the real possibility that gut pathology may exist. This route is therefore restricted for use in facilitating fluid replacement and is used mainly for nutritional support and rehydrating the gut microflora.

Syringe drivers

For continuous fluid administration, such as is required for intravenous and intraosseous fluid administration, syringe drivers are recommended. Their advantage is that small volumes may be administered accurately. An error of 1–2 mL in some of the species dealt with over an hour could be equivalent to an over-perfusion of 50–100%! In addition, it is almost impossible to keep gravity-fed drip sets running at these low rates.

Intravenous drip tubing

Fine drip tubing is available for attachment to syringes and syringe-driver units. It is useful if these are luer locking, as this enhances safety and prevents disconnection when the patient moves. It may be necessary to purchase a sheath, such as is available for protecting household electrical cables, to cover drip tubing, as most of the small herbivores are experts at removing or chewing through plastic drip tubing!

Elizabethan collars

It may be necessary to place some of the small herbivores into an Elizabethan-style collar as they are the world’s greatest chewers! These can be purchased as cage bird collars and adapted to fit even the smallest of rodents.

Routes of fluid administration

These routes have their advantages and disadvantages, given in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3 The advantages and disadvantages of various fluid therapy routes in small mammals.

| Route | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Oral | Reduced stress Well accepted Physiological route Minimal tissue trauma Rehydration of gut flora | May increase stress in guinea pigs Risk of aspiration pneumonia in some Not useful in cases of gut disease Slow rates of rehydration Maximum volume is 10 mL/kg |

| Subcutaneous | Large volumes may be given reducing dosing frequency Minimal risk of organ puncture | Guinea pigs react badly to scruff injections and fur slip is common in chinchillas Slow rehydration time May impede respiration due to pressure on chest wall Hypotonic or isotonic crystalloid fluids only |

| Intraperitoneal | Large volumes may be given at one time Uptake faster than subcutaneous if mild dehydration is present Minimal discomfort | Risk of organ puncture Stressful positioning (dorsal recumbency) Pressure on diaphragm may increase; respiratory effort needed Isotonic or hypotonic crystalloids only |

| Intravenous | Rapid central venous support May be used for continuous perfusion Can be used for colloidal fluids, hypertonic saline, dextrose/glucose and blood transfusions/replacers | Minimal peripheral access in some species (e.g. hamsters, gerbils) Increased vessel fragility due to small patient size Requires increased levels of operator skill |

| Intraosseous | Rapid support of the central venous system Useful in collapsed and very small patients where vascular access is difficult May still be used for blood transfusions/replacers Minimal risk of organ damage (puncture) | Not useful in fragile bones or metabolic bone disease Not useful in bone fractures or osteomyelitis Increased risk of infection (osteomyelitis) Painful procedure requiring sedation/analgesia Continuous perfusion required (syringe drivers) otherwise maximum boluses are small (0.25–0.5 mL for myomorph rodents and sugar gliders, 1–2 mL for hystricomorph rodents, 2–3 mL for rabbits, Virginia opossums and ferrets) |

Oral

Rabbit

The oral route is not good for seriously debilitated rabbits, but it is useful for those with naso-oesophageal feeding tubes in place. It may also be useful for mild cases of dehydration where owners wish to home treat their pet. This route is restricted to small volumes, with a maximum of 10 mL/kg administered at any one time.

Rat, mouse, gerbil and hamster

Gavage (stomach) tubes or avian straight crop tubes can be used to place fluids directly into the rodent oesophagus. The rodent needs to be firmly scruffed to adequately restrain it with the head and oesophagus in a straight line. This method is often stressful but the alternative is to syringe fluids into the mouth, which often does not work as rodents can close off the back of the mouth with their cheek folds. Maximum volumes which can be given via the oral route in rodents vary from 5 to 10 mL/kg. Naso-oesophageal or gastric tubes are not a viable option in rodents due to their small size.

Guinea pig and chinchilla

Naso-oesophageal tubes may be placed and doses of

10 mL/kg may be administered at any one time. Guinea pigs and chinchillas are more likely to regurgitate

than rabbits, especially when debilitated, so care is needed.

Marsupial

Gavage (stomach) tubes or avian straight crop tubes can be used to place fluids directly into the marsupial oesophagus. The marsupial needs to be firmly scruffed to adequately restrain it and to keep the head and oesophagus in a straight line. Alternatively, fluids may be drip fed from a syringe or teaspoon into the lip sulcus either side of the mouth and lapped up from there.

Ferret

Naso-oesophageal tubes are not well tolerated in ferrets, but many will accept sweet-tasting oral electrolyte solutions from a syringe. Ferrets, especially when debilitated, can regurgitate, so care is needed.

Subcutaneous

The advantages and disadvantages of this method are given in Table 6.3.

Rabbit

The scruff or lateral thorax makes ideal sites. This is a good technique to use as routine post-operative administration of fluids for minor surgical procedures such as spaying or castration. It is possible to give a maximum of 30–60 mL split into two or more sites at one time depending on the size of rabbit.

Rat, mouse, gerbil and hamster

The scruff area is easily utilised for volumes of 3–4 mL of fluids for smaller rodents and up to 10 mL at any one time for rats. The use of a 25-gauge needle is recommended.

Guinea pig and chinchilla

This is an easily used route for post-operative fluids and mild dehydration in these species. The scruff area and lateral thorax are preferred sites (Figure 6.1). The scruff may be painful for guinea pigs as it is a site of brown fat deposition and well innervated. Doses of 25–30 mL may be given at one time, preferably at two or more sites. Fur slip is a problem in chinchillas.

Figure 6.1 Subcutaneous fluids being administered in the scruff region in a chinchilla post-operatively.

Marsupial

This is an easily used route for post-operative fluids and mild dehydration in these species. The scruff area and lateral thorax are preferred sites. Volumes of 3–4 mL in sugar gliders and 15–20 mL in adult Virginia opossums may be administered.

Ferret

Volumes of 15–20 mL may be given in two or more sites over the scruff.

Intraperitoneal

The advantages and disadvantages of the intraperitoneal route in small mammals are given in Table 6.3.

Rabbit

The rabbit is placed in dorsal recumbency to allow the gut contents to fall away from the injection zone. The needle is inserted in the lower right quadrant of the ventral abdomen, just through the abdominal wall and the syringe plunger drawn back to ensure that no

puncture of the bladder or gut has occurred. A maximum volume of 20–30 mL may be given at one time depending on the size of the rabbit. Previous notes regarding concurrent respiratory or cardiovascular disease should be considered. If positioned correctly, there should be no resistance to injection.

Rat, mouse, gerbil and hamster

The positioning and administration site for rodents is as for rabbits (Figure 6.2). The needle should be 25 gauge or smaller and maximal volumes of 1–4 mL in smaller rodents, up to 10 mL in large rats, may be given.

Figure 6.2 Intraperitoneal fluids administered to a rat showing positioning required for safe administration to avoid organ puncture.

Guinea pig and chinchilla

Similar principles apply for this route as for rabbits and other rodents. Doses of 15–20 mL may be given. This is a good route for more serious cases, as intravenous fluids are not so well tolerated, particularly in chinchillas and guinea pigs.

Marsupial

Similar principles apply for this route as for rabbits and rodents. Doses of 2–4 mL in sugar gliders and 15–20 mL in Virginia opossums may be given.

Ferret

The technique is as for rabbits. Restraint may be difficult in the conscious patient, and maximum volumes are 20–25 mL.

Intravenous

The advantages and disadvantages of intravenous fluid therapy in small mammals are given in Table 6.3.

Rabbit

The blood vessel that is best tolerated is the lateral ear vein. The technique for using it is described below.

Lateral ear vein

The following technique should be used (Figure 6.3):

Cephalic vein:

This may be used as for the cat and dog, although this vein may be split in some rabbits: A 25–27 gauge over-the-needle or butterfly catheter may be used for access and taped in as for cats and dogs.

Saphenous vein:

For this, it is better to use a 25–27 gauge butterfly catheter as it is relatively fragile. It runs over the lateral aspect of the hock (Figure 6.4).

All of these routes can be used for intravenous boluses of up to 10 mL for larger rabbits and 5 mL for smaller dwarf breeds; but for continuous therapy, a syringe driver is required.

Rat, mouse, gerbil and hamster

The intravenous route in hamsters and gerbils is extremely difficult, as they have few peripheral veins and the tail veins in gerbils are dangerous to use due to the risk of tail separation. In mice and rats, the lateral tail veins may be used. An intravenous bolus of fluids can be given using a 25–27 gauge insulin needle or by insertion of a butterfly catheter (Figure 6.5). Warming the tail and applying local anaesthetic cream will help to dilate the vessels and make venipuncture easier. Volumes of 0.2 mL in mice and up to 0.5 mL in rats as a bolus may be given. It is also possible to perform a cut-down jugular catheterisation, but this requires anaesthesia.

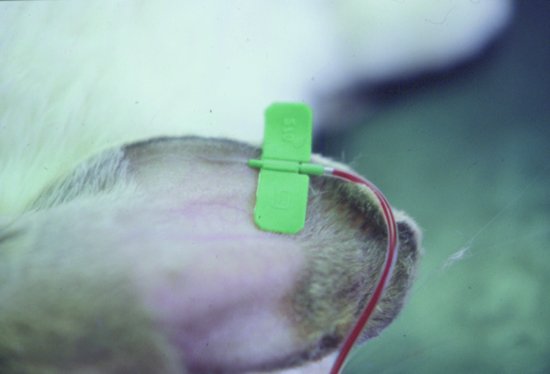

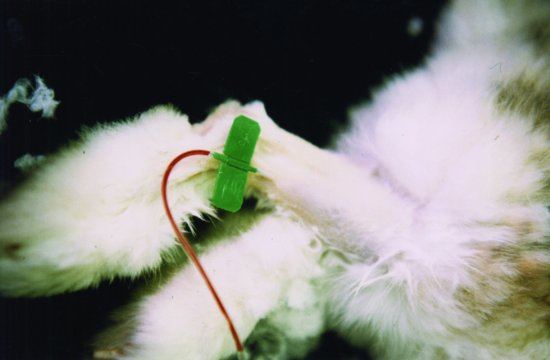

Figure 6.5 Blood transfusion in a rat. Blood is administered to an anaesthetised patient via the tail vein, here in a pre-heparinised syringe.

Guinea pig and chinchilla

The cephalic and saphenous veins may be used – but generally these are very small and difficult to catheterise. A cut-down technique may be used to access the jugular veins in an emergency.

Jugular vein catheterisation

Sedation or anaesthesia is necessary for this procedure, which is as follows:

Marsupial

Sugar gliders are difficult to catheterise consciously because of their small size. The jugular vein is the easiest to catheterise in the sedated animal for significant fluid administration but tolerance of these catheters is poor. Other peripheral vessels such as the saphenous and cephalic are only accessible with 25–27 gauge needles. In Virginia opossums, the cephalic or saphenous veins are the most accessible. In addition, the lateral tail vein may also be used. However, tolerance of indwelling catheters in the conscious animal is poor and so maintenance is difficult.

Ferret

Ferrets are difficult to catheterise when fully conscious. The cephalic vein may be used with 24–27 gauge

over-the-needle catheters; however, movement once consciousness has been regained frequently dislodges these catheters, and ferrets will often chew the dressings off. Bolus therapy, when unconscious, may be preferable with 5–10 mL given over several minutes.

Intraosseous

The advantages and disadvantages of this route in small mammals are given in Table 6.3.

Rabbit

The proximal femur is the easiest to use. The landmark to aim for is the fossa between the hip joint and the greater trochanter. A 20–23 gauge hypodermic needle or spinal needle is used, and the procedure requires sedation. The area is surgically prepared and the needle is screwed into position in the same direction as the long axis of the femur. It may be necessary to cut down through the skin with a sterile scalpel blade in some rabbits. This method will require a syringe-driver perfusion device.

It is possible to use the proximal tibia but this is less well tolerated due to interference with the stifle joint. There is frequently a need for tubing guards or Elizabethan collars for all intravenous or intraosseous techniques.

Rodents

The proximal femur may be tolerated as for rabbits in larger rats but smaller species often have a too small medullary cavity for needles to be safely inserted.

Hystricomorphs

This is the preferred route for severely dehydrated chinchillas and guinea pigs with the proximal femur being the easiest site. Access is via the natural fossa created by the hip joint and the greater trochanter. Infusion devices such as syringe drivers are advised for this route of administration (Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6 Intraosseous catheter placement in a guinea pig using the proximal femur, showing attachment to drip set and infusion device, and before bandaging in place.

Marsupial

The proximal femur is the easiest bone to use for intraosseous fluid administration. The landmark to aim for is the fossa between the hip joint and the greater trochanter. Insertion is as for rabbits and guinea pigs. In the sugar glider, due to their small size, a 25-gauge needle is required. In Virginia opossums, a 21–23 gauge needle may be used. These are slightly better tolerated than intravenous catheters.

Ferrets

The proximal femur is the easiest bone to use for intraosseous fluid administration. The landmark to aim for is the fossa between the hip joint and the greater trochanter. Insertion is as for rabbits.

Drug toxicities in small mammals

Lagomorpha

Drugs of the penicillin family should not be used orally due to their ability to cause an enterotoxaemia with Clostridia spp. gut overgrowth. The same is true of the cephalosporin and the macrolide family such as clindamycin. Other antimicrobial additives to avoid in rabbits include procaine, which is often added to penicillin preparations.

Muridae

Medications containing procaine (such as procaine penicillin) and streptomycin have been reported as causing toxicity in mice and rats.

Gerbils (Cricetidae)

Gerbils are sensitive to streptomycin and dihydrostreptomycin containing antimicrobials. They are mildly affected by potentiated penicillins orally, and these should be used with care. It is not advised to use any macrolides in gerbils (e.g. clindamycin, erythromycin).

Hamsters (Cricetidae)

The following antimicrobials should never be used in hamsters because of their ability to cause a fatal enterotoxaemic condition and in the case of the aminoglycosides because of the risks of renal damage and ototoxicity: all penicillins, all cephalosporins, all macrolides (clindamycin, erythromycin, etc.), the aminoglycosides, streptomycin, dihydrostreptomycin and oral gentamicin.

Guinea pigs (Hystricomorpha)

The following antimicrobials should not be used in guinea pigs for fear of causing a fatal enterotoxaemic condition: all penicillins, all cephalosporins and all macrolides.

Chinchillas (Hystricomorpha)

The following antimicrobials should not be used in chinchillas for fear of inducing a fatal enterotoxaemia: all penicillins, all cephalosporins and all macrolides. Metronidazole has been associated with liver failure in chinchillas, but this author has not experienced this problem.

Chipmunks (Sciuromorpha)

Avoid the macrolide family and oral penicillins as both can cause diarrhoea, particularly the former.

Marsupials

Omnivorous marsupials such as the sugar glider and the Virginia opossum seem to be generally unaffected by most antimicrobials.

Ferrets

Ferrets are generally unaffected by most antimicrobials.

TREATMENTS FOR DISEASES IN SMALL MAMMALS

The tables in this section are intended to give an overview of the therapies available and are by no means comprehensive. Readers are advised to consult one of the many excellent texts listed at the end of this chapter for further information.

Lagomorph disease therapies

Tables 6.4–6.8 discuss common treatments for selected diseases of lagomorphs on a system basis.

Table 6.4 Treatment of selected skin diseases in lagomorphs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Mites, lice and fleas | Ivermectin/selamectin are the drugs of choice for mites and lice. Various preparations of ivermectin are available under the small animal exemption scheme (SAES) in the United Kingdom (e.g. Xeno450®, Dechra Veterinary Products). Imadocloprid (Advantage®, Bayer) is licensed for treating fleas in rabbits and combined with moxidectin (Advocate®, Bayer) for ferrets in the United Kingdom. |

| Blowfly strike | Prevention by removing urine and faecal soiling. Fine mesh to cover outdoor hutch openings. The use of topical growth inhibitor cyromazine (Rearguard®, Novartis Animal Health) preventing maggot maturation. Once infected, manually remove maggots and use ivermectin, covering antimicrobials and fluid therapy. |

| Bacterial diseases | Based on culture and sensitivity results. Blue fur disease requires a fluoroquinolone (e.g. enrofloxacin). Rabbit syphilis (Treponema paraluiscuniculi infection) requires injectable penicillin. |

| Dermatophytosis | Miconazole spray licensed under the SAES (Mycozole®, Dechra Veterinary Products) in rabbits in the United Kingdom. Oral itraconazole may be used at 5 mg/kg once daily. Oral griseofulvin can be used, although not in pregnant does due to its terratogenic side effects. |

| Myxomatosis | No treatment. Prevention is by vaccination, which recently has changed to a combined myxomatosis/VHD vaccine in the United Kingdom (NobiVac Myxo-RHD®, MSD Animal Health). |

Table 6.5 Treatment of selected digestive system diseases in lagomorphs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Dental disease | Prevention by access to good quality hay, dried grass or fresh grazing is essential. Homogenous pelleted grass-based foods are also useful. Once teeth are overgrown, regular burring to a normal shape must be performed every 6–8 weeks. |

| Gastrointestinal foreign body | Digestive lubricants, liquid paraffin, fluid therapy and prokinetic drugs, if there is no evidence of a complete obstruction. Surgery should be considered if tests indicate a complete obstruction. |

| Diarrhoea | Fluid therapy. Cause must be determined before treatment. If suspect clostridial overgrowth, then use oral cholestyramine (Questran®, Par Pharmaceutical Inc., a human product) to bind toxins and prevent absorption plus potentially metronidazole to kill the clostridia. The suspected bacterial cause of ERE has been treated by using tiamulin (licensed in feed product Denagard 2% or Denagard 10% w/w Medicated premix for pigs, chickens, turkeys and rabbits®, Novartis Animal Health Ltd.). Coccidiosis: Use oral sulfadimidine at 1 g/L of drinking water for 7 days. Repeat after 7 days. Alternatively, infeed preparations are licensed for rabbits in the United Kingdom containing diclazuril (Clinacox 0.5% Premix®, Huvepharma NV), robenidine hydrochloride (Cycostat 66G®, Pfizer Animal Health Ltd.). Nematode infections treated with an ivermectin injection at 0.2 mg/kg (various products licensed under the SAES in the United Kingdom, see Skin Diseases) or oral fenbendazole at 20 mg/kg once daily for 4 days (various products licensed under the SAES in the United Kingdom, e.g. Lapizole®, Dechra Veterinary Products; Panacur Rabbit 18.75% oral paste®, MSD Animal Health). Bacterial enteritis may be treated according to culture and sensitivity results. Loperamide may be used to symptomatically reduce diarrhoea. |

| Hypomotility disorder | Dietary management is important. Use of prokinetics, e.g. cisapride (0.5 mg/kg q12 hours), ranitidine (2–5 mg/kg q12 hours) and metoclopramide (0.5 mg/kg q8–12 hours), is required. Fluid therapy is essential with oral pre/probiotics or transfaunation (taking caecotrophs from a healthy rabbit and mixing them with food to administer to the patient). |

| Hepatic lipidosis | Prokinetics (if obstructive cause ruled out), e.g. ranitidine, metoclopramide and cisapride. Assisted feeding is important with soluble carbohydrates initially to ensure correct calorie supply. Transfaunation of caecotrophs from a healthy donor or pre/probiotics are helpful. Use of L-carnitine, extract of milk thistle and inositol are helpful in supporting hepatocyte function. |

Table 6.6 Treatment of selected respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in lagomorphs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Pasteurellosis | Fluid therapy. Treatment with fluoroquinolone (in the UK, Baytril 2.5% Injection® or Baytril 2.5% oral solution®, Bayer Animal Health, are licensed) or sulphonamide antimicrobial is advised. In commercial rabbit production, tilmicosin in feed is licensed in the United Kingdom for treating pasteurellosis (Pulmotil G100 Premix for medicated feedstuff®, Elanco Animal Health). Mucolytics (e.g. bromhexine hydrochloride orally or acetylcysteine via nebulisation) and manual cleaning of the nares. |

| Viral haemorrhagic disease (VHD) | No treatment. Vaccination is possible using a combined myxomatosis/VHD vaccine in the United Kingdom (NobiVac Myxo-RHD®, MSD Animal Health). This is currently at time of press dosed as one dose per rabbit from 5 weeks of age and boostered at yearly intervals. Alternatively, single VHD vaccines are available (e.g. Cylap®, Pfizer Animal Health; Lapinject VHD®, CEVA Animal Health Ltd.). |

| Congestive heart failure | This is the end-stage of heart disease and may have multiple initial causes. Treatment is based on reducing fluid congestion with diuretics, e.g. furosemide (1–4 mg/kg as required) and spironolactone (1–2 mg/kg q24 hours); reducing the afterload, the heart has to work against with ACE inhibitors (watch for hypotension as rabbits are more sensitive to this than cats and dogs, so usually a lower dose of drugs such as benazepril is advised at 0.1–0.2 mg/kg (Girling, 2003); positive inotropes such as pimobendan (0.25 mg/kg twice daily). If atrial fibrillation is present, then digoxin has been used at 0.005–0.01 mg/kg orally q24–48 hours. If heart blocks and bradycardia are seen, then glycopyrrolate at 0.01 mg/kg. |

Table 6.7 Treatment of selected urogenital tract diseases in lagomorphs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Urolithiasis | Catheterising, flushing bladder and aggressive fluid therapy. Surgery occasionally required. Reduce dietary calcium and restrict dry food to maximum 25–30 g/day. Antimicrobials and analgesia may be needed, if concurrent cystitis. Radiographs are helpful to look for renoliths, which will worsen the prognosis. |

| Chronic renal failure | Aggressive fluid therapy – initially intravenously or intraosseously, but may be supported by subcutaneous fluids once stabilised. Treatment of exacerbating conditions, e.g. pyelonephritis, urolithiasis/renolithiasis and encephalitozoonosis. ACE inhibitors, e.g. benazepril, have been shown to be helpful in increasing renal perfusion as has been seen in domestic cats, but rabbits are more prone to hypotension and so dosages should be reduced (0.1–0.2 mg/kg q24 hours) (Girling, 2003). Anabolic steroids to prevent catabolism every 3–4 weeks along with multiple B vitamins can help with appetite. Prokinetics, e.g. cisapride, ranitidine or metoclopramide, may also be required to maintain gut motility. The reduction of protein in the diet as well as phosphate salts may help preserve renal function – that is, reducing pelleted portion of the diet and increasing leafy greens. |

| Uterine adenocarcinoma | Treatment by surgical spaying. Prevention is by surgical spaying at 4–5 months of age. |

| Venereal spirochaetosis | Penicillin G, single dose, subcutaneously at 40 000 IU/kg. May need to repeat after 7 days. Care should be taken as it can be toxic if given orally. |

| Mastitis | Antibiosis based on culture and sensitivity (fluoroquinolones such as enrofloxacin usually effective as bacteria are frequently E. coli or Pasteurella spp.). Analgesia with carprofen 5 mg/kg, meloxicam 0.3–0.6 mg/kg daily. Fluid therapy and supportive treatment is essential. |

Table 6.8 Treatment of selected musculoskeletal, nervous system and ocular diseases in lagomorphs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Osteoarthritis | NSAIDs, e.g. meloxicam, at 0.3–0.6 mg/kg q24 hours have proved useful. More advanced cases may require multimodal analgesia with drugs such as tramadol (10 mg/kg q24 hours) or buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg q8–12 hours). |

| Fractures | Spinal dislocations and fractures with hindlimb paresis carry poor prognosis, but shock doses of short-acting corticosteroids, e.g. methylprednisolone, are considered if administered within 12 hours of injury. Otherwise, use NSAIDs such as meloxicam. Limb fractures carry a better prognosis. Most require external/tie-in fixators as rabbit bones are brittle with large medullary cavities. Consider calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in cases of metabolic bone disease. |

| Vestibular disease due to otitis media | Fluoroquinolone or sulphonamide antimicrobials are useful where Pasteurella or Streptococcal infections are present. Anaerobic infections may require injectable penicillins. Surgical removal of the lateral wall of the external ear canal can relieve pressure in the short narrow horizontal canal. Bulla osteotomy is difficult and failure rates are high due to the tenacious pus, deep seated nature of the bullae and their small size. Prognosis is guarded for full recovery, but generally not life-threatening if due to uncomplicated otitis media. |

| Encephalitozoonosis | Fenbendazole at 20 mg/kg orally once daily for 28 days (Suter et al., 2001). Short-acting corticosteroids have been used in severe cases with some success in addition to fenbendazole (Harcourt-Brown & Holloway, 2003). Management of renal disease may also be required (see urogenital section). Prognosis guarded once neurological disease is apparent. |

| Lead poisoning | Removal of larger particles by surgery may be possible but frequently the particle size is very small. Treatment with chelating agent, e.g. sodium calcium edetate (27.5 mg/kg q6–8 hours for 5 days), combined with fluid therapy to reduce nephrotoxicity. |

| Anterior uveitis | Test for encephalitozoonosis and treat if positive (see above). Analgesia with systemic NSAIDs plus use of topical tropicamide drops to prevent synechiae formation. Phacoemulsification of the lens and removal may be necessary. |

| Dacryocystitis | Not a true ocular problem but a dental problem with constriction of the tear duct by elongating maxillary incisor root. Treatment is reliant on controlling the dental problem and cannulating and flushing the tear duct. |

| Conjunctivitis | This may occur secondarily to dacryocystitis or as a primary problem. Topical eye drops using fucidic acid (e.g. Fucithalmic Vet®, Dechra Veterinary Products) or gentamicin (e.g. Tiacil®, Virbac Animal Health) are licensed for use in rabbits with conjunctivitis in the United Kingdom. |

Muridae disease therapies

Tables 6.9–6.11 discuss common treatments for selected diseases of Muridae (rats and mice, chiefly) on a system basis.

Table 6.9 Treatment of skin diseases in Muridae.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Mites | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg is advised (several products licensed under the SAES in the United Kingdom, see rabbit skin diseases). |

| Lice and fleas | Ivermectin orally/spot-on. |

| Bacterial disease | Based on culture and sensitivity results. Pododermatitis may require surgical debridement, analgesia (carprofen/meloxicam) and hydrating gels/dressings, as well as improving cage substrate to increase padding. Weight loss also advisable. |

| Dermatophytosis | Topical miconazole available under the SAES in the United Kingdom (Mycozole®, Dechra Veterinary Products). Oral griseofulvin has been used, but beware of terratogenicity in pregnant females. Oral itraconazole has also been used (5 mg/kg q24 hours) but beware of hepatotoxicity and anorexia. |

| Atopy | Topical soothing shampoos (e.g. Episoothe®, Virbac) and oral essential fatty acids (oil of evening primrose). Oral corticosteroids have been used in acute flare-ups but long-term use has side effects. Oral antihistamines have also been tried with varying success. |

Table 6.10 Treatment of selected digestive, respiratory and cardiovascular system diseases in Muridae.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Dental disease | Burring, every 3–4 weeks with a low speed dental burr, is advised for incisor malocclusion. |

| Parasitic disease | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg once (see Skin Disease) or fenbendazole at 20 mg/kg orally once daily for 5 days for nematodes. For coccidiosis, use sulfadimidine in water at 200 mg/L for 7 days. Metronidazole is useful for other protozoa. |

| Bacterial disease | Enrofloxacin (Baytril 2.5% oral solution®, Bayer Animal Health) is effective against a wide range of Gram-negative bacterial infections and is licensed for use in rodents in the United Kingdom. Oxytetracycline is used for Tyzzer’s disease at 0.1 g/L drinking water. Other treatments based on culture and sensitivity. |

| Respiratory disease | Culture and sensitivity advised. Oxytetracycline, doxycycline, azithromycin and enrofloxacin are useful against Mycoplasma spp., Streptococcus pneumonia and Klebsiella spp. infections. Consider mucolytics, e.g. bromhexine hydrochloride orally or acetylcysteine by nebulisation. Nebulisation of antimicrobials may also be helpful. |

| Cardiovascular disease | See protocols and drugs for rabbits. |

Table 6.11 Treatment of selected urogenital tract, musculoskeletal, neurological and ocular diseases in Muridae.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Chronic renal failure | Reduce dietary protein, but increase the biological value. Reduce phosphate in diet (if necessary, use aluminium hydroxide orally to bind phosphorus in the gut and prevent absorption). Fluid therapy – preferably intravenously/intraosseously initially to stabilise. Anabolic steroids and B vitamin supplementation. |

| Urolithiasis | Removal of blockages manually. Reduce calcium content of diet and increase bran levels. Antimicrobials for preputial gland abscess/cystitis. |

| Spondylosis | Meloxicam at 0.5–1 mg/kg orally once/twice daily for pain relief. |

| Fractures | Splinting and strict confinement plus analgesia (NSAID); allow rapid callus formation and repair (2–3 weeks). |

| Vestibular disease | If bacterial, use fluoroquinolone or sulphonamide antimicrobials. If caused by a pituitary tumour, surgery rarely possible. |

| Keratoconjunctivitis sicca | Topical cyclosporin has been used successfully. |

Cricetidae disease therapies

Tables 6.12–6.15 discuss common treatments for selected diseases of Cricetidae (gerbils and hamsters, chiefly) on a system basis.

Table 6.12 Treatment of skin diseases in gerbils.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Demodicosis | Amitraz washes (1 mL solution to 0.5 L water) once every 2 weeks until negative scrapings. Beware toxicity. Alternatively ivermectin at 0.4 mg/kg once weekly for 6 weeks has been used. |

| Bacterial disease | Oral or parenteral antibiosis based on culture and sensitivity results. Enrofloxacin orally or in water, oxytetracycline at 0.8 mg/L water may be useful. |

| Dermatophytosis | Topical miconazole available under the SAES in the United Kingdom (Mycozole®, Dechra Veterinary Products). Oral griseofulvin has been used, but beware of terratogenicity in pregnant females. Oral itraconazole (5 mg/kg q24 hours) but beware of hepatotoxicity and anorexia. |

| Neoplasia | Surgical excision of ventral scent gland adenocarcinomas or melanomas is advised. |

| Degloving injuries | Fluid therapy. Topical anticoagulants (calcium sprays) or pressure to stem bleeding. Topical/parenteral antimicrobials advised. May need surgery to remove denuded coccygeal vertebrae. |

Table 6.13 Treatment of selected digestive, respiratory and urogenital system diseases in gerbils.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Proliferative ileitis (wet tail – Lawsonia intracellularis infection) | Difficult, but oxytetracyclines and chloramphenicol have been suggested. |

| Parasitic disease | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg for nematode infestations. Praziquantel at 10 mg/kg orally once for Rodentolepis nana may need to repeat after 2 weeks. |

| Respiratory disease | Treatment is as for Muridae |

| Cystic ovarian disease | Surgical spaying is curative. Alternatively, percutaneous drainage or human chorionic gonadotrophin at 100 IU/kg may remove the cysts for a time but they will re-occur. |

Table 6.14 Treatment of selected skin and digestive system diseases in hamsters.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Demodicosis | Amitraz is the treatment of choice but ivermectin may also be used (see Gerbils). However, the problem is often an underlying immunosuppressive disease that allows the mites to proliferate and so without correcting this treatments may be unsuccessful. |

| Sarcoptiform mange (Notoedres notoedric) | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg once weekly on 2–4 occasions. |

| Dermatophytosis | See dermatophytosis in Table 6.12. |

| Hyperadrenocorticism | This is often untreatable. Surgery is generally too complicated with high failure rates. Metapyrone has been used at 8 mg orally once daily, but this is potentially toxic and may result in the death of the hamster. |

| Cheek pouch impactions | Milking the contents manually or with a dampened cotton bud is advised. Flushing the pouches with dilute chlorhexidine can remove any superficial infection. |

| Cheek pouch prolapse | Surgical replacement with a cotton bud under anaesthesia. A suture may be placed through the skin into the cheek pouch behind the ear to keep in place. |

| Proliferative ileitis (wet tail due to Lawsonia intracellularis infection) | Extremely difficult, see Gerbils. |

Table 6.15 Treatment of selected cardiovascular, endocrine, reproductive and musculoskeletal diseases in hamsters.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Aortic thrombosis and cardiomyopathy | Use of furosemide at 0.25–0.5 mg/kg may be useful, as may the ACE inhibitor enalapril at 0.25 mg/kg orally once daily. Beware of hypotensive effects. |

| Hyperadrenocorticism | See Skin Diseases. |

| Diabetes mellitus | Protamine zinc insulin therapy at 0.5–1 unit/kg (requires dilution in saline). Aim for 0.25–0.5% glucose in urine and water consumption 10–15 mL/day. Use glucose/saline intraperitoneally and human glucose oral gels on membranes if evidence of hypoglycaemic overdose. |

| Pyometra | Surgical neutering after fluid therapy and antimicrobial stabilisation. |

| Cystic ovarian disease | Surgical spaying is curative. Alternatively, percutaneous drainage or human chorionic gonadotrophin at 100 IU/kg may remove the cysts for a time but they will re-occur. |

| Fractures | Compound fractures of the tibia may require leg amputation. If closed they may heal conservatively with rest and analgesia. Intramedullary pinning with 25–27 gauge needles are possible. |

Hystricomorph disease therapies

Tables 6.16–6.20 discuss common treatments for selected diseases of hystricomorphs on a system basis (chiefly chinchillas and guinea pigs).

Table 6.16 Treatment of selected skin diseases in guinea pigs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Mites | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg is effective against Trixicara caviae (various products licensed under the SAES in the United Kingdom). Analgesics (e.g. meloxicam) and tranquilisers (e.g. diazepam) may be necessary in severe cases. |

| Lice | Fipronil sprayed on to a cloth and then wiped over the fur. Ivermectin may also be useful. |

| Cervical lymphadenitis | Surgical lancing of the abscess and treatment with antimicrobials (e.g. enrofloxacin) is advised. |

| Dermatophytosis | See dermatophytosis in Table 6.12. |

| Pododermatitis | See bacterial diseases in Table 6.9. |

Table 6.17 Treatment of selected digestive, respiratory and urinary system diseases in guinea pigs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Dental disease | This is similar to rabbits. Change the diet to increase, abrasive, grass-based foods. Burr molar spikes every 6–8 weeks under sedation. Treat oral infections based on culture and sensitivity +/– information. |

| Bacterial disease | As for hamsters and gerbils, it is based on culture and sensitivity. Enrofloxacin useful for Salmonella spp. |

| Parasitic disease | Nematodes may be treated with 0.2 mg/kg ivermectin. Coccidiosis requires oral sulfadimidine at 40 mg/kg, once daily for 5 days. B. coli require metronidazole orally but use with caution due to risk of liver damage. |

| Faecal impaction | Manual emptying of perianal skin folds daily and flushing with dilute chlorhexidine. |

| Respiratory disease | Enrofloxacin, doxycycline and sulphonamide drugs are useful. Mucolytics, e.g. oral bromhexine hydrochloride and nebulised acetyl cysteine, are useful. Nebulised antimicrobials also helpful. Neoplasia often so advanced by the time diagnosis is made, that treatment is not possible. |

| Chronic renal failure | See chronic renal disease of rabbits in Table 6.7. |

| Urolithiasis | Restriction of dry food to 15–20 g/day to reduce dietary calcium levels. Fresh vegetables and fluids to help flush through calcium crystals. Treat with antimicrobials if cystitis is suspected. |

Table 6.18 Treatment of selected reproductive, ocular and musculoskeletal diseases in guinea pigs.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Cystic ovarian disease | See hamsters in Table 6.15. |

| Pregnancy toxaemia | Oral glucose gel, intravenous or intraperitoneal glucose-saline as a 5–7 mL bolus. Dexamethasone 0.2 mg/kg intramuscularly (but will cause abortion). To prevent, do not let sow become overweight or stressed. |

| Mastitis | Antimicrobials such as enrofloxacin or sulphonamides with fluid therapy and NSAID analgesia. Surgery may be necessary. |

| Hypovitaminosis C (‘Scurvy’) | Vitamin C parenterally at 50 mg/kg and 200 mg/L drinking water. |

| Fractures | Splinting with hexalite materials plus cage restriction and analgesia. Surgical fixation with external fixators. Methyl-prednisolone may be needed if spinal trauma is involved and treatment can be administered within 12 hours. Otherwise NSAID use is preferred. |

| Conjunctivitis | Chlortetracycline eye ointment for Chlamydophila psittaci conjunctivitis. See scurvy for vitamin C related problems. |

Table 6.19 Treatment of selected skin and digestive system diseases in chinchillas.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Dermatophytosis | See dermatophytosis in Table 6.12. |

| Dental disease | As for rabbits – dental burring under sedation every 6–8 weeks, dietary change to grass-based products. Analgesia for root pain using meloxicam +/– tramadol orally. Use of prokinetics such as cisapride (0.5 mg/kg q12 hours), ranitidine (2–5 mg/kg q12 hours) and metoclopramide (0.5 mg/kg q8–12 hours). Use of antimicrobials based on culture and sensitivity testing although anaerobes are common and so oral metronidazole at 10–20 mg/kg q12 hours (some texts suggest metronidazole is hepatotoxic in chinchillas so beware its overuse). |

| Hypomotility disorder (‘colic’) | This is generally associated with digestive tract disease or pain and so the cause of the discomfort/disease needs to be determined to ensure proper treatment. Symptomatic treatment of hypomotility can include fluid therapy, analgesia (e.g. meloxicam) and prokinetics as outlined for dental disease. |

| Hepatic lipidosis | Reduce excess fats and soluble carbohydrates in diet. Fluid therapy and assisted nutrition/feeding (e.g. B vitamins, L-carnitine, inositol and milk thistle) extract to support hepatocyte function. |

| Bacterial diarrhoea | Antimicrobial treatment is based on culture and sensitivity results. Fluid therapy and analgesia as well as assist feeding may also be required. |

| Parasitic diarrhoea | Treatment of giardiasis with fenbendazole at 25 mg/kg orally once daily for 3 days. Some texts avoid metronidazole due to hepatotoxicity, but this author has used it for dental disease and giardiasis at 10–20 mg/kg orally twice daily for 7 days without any side effects. |

Table 6.20 Treatment of selected cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, nervous and ocular diseases in chinchillas.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Congestive heart failure associated with dilated cardiomyopathy | Treatment is based on reducing fluid congestion with diuretics such as furosemide (1–4 mg/kg as required) and spironolactone (1–2 mg/kg q24 hours); reducing the afterload the heart has to work against with ACE inhibitors such as enalapril/benazepril; positive inotropes such as pimobenden. If atrial fibrillation is present, then digoxin has been used at 0.005–0.01 mg/kg orally q24–48 hours. |

| Fractures | Long bone fractures are best fixed with external fixation surgically. Smaller fractures may be splinted with human finger splints. |

| Seizures | Symptomatic treatment with 1–2 mg/kg diazepam intramuscularly. Heat stroke treated with cooled intravenous/peritoneal fluids. Listeriosis with oxytetracycline 10 mg/kg twice daily intramuscularly. |

| Conjunctivitis | Use of chlortetracycline eye ointments is recommended for Chlamydophila psittaci. Always check for dental disease in any case of epiphora as molar root elongation pressing on the globe is a common cause of epiphora in chinchillas. |

Sciuromorph disease therapies

Tables 6.21 and 6.22 discuss common treatments for selected diseases of sciuromorphs (chiefly chipmunk) on a system basis.

Table 6.21 Treatment of selected skin, digestive and respiratory system diseases in chipmunks.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Mites | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg is advised. In addition, for Dermanyssus gallinae, burn bedding and dust cage with bromcyclen powder. |

| Bacterial skin disease | Antimicrobials based on culture and sensitivity. Generally, enrofloxacin, tetracycline and sulphonamides are safe and effective. |

| Dental disease | Burring of incisor malocclusion with a slow speed dental drill every 4–6 weeks. |

| Diarrhoea | As for rats and mice. |

| Respiratory disease | Oxytetracycline at 22 mg/kg once daily for 5–7 days is useful for Mycoplasma spp. Enrofloxacin and doxycycline may also be used. |

Table 6.22 Treatment of selected urogenital, musculoskeletal and nervous system diseases in chipmunks.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Urolithiasis | Surgical or manual removal of obstructing uroliths. Give meat-based foods temporarily to acidify urine and dissolve crystals, or increase seeds and fruits and reduce pelleted food. |

| Hypocalcaemic paralysis | 100 mg/kg calcium gluconate intramuscularly. Prevention based on dietary supplementation. Beware that some of these cases are actually associated with spinal trauma and not hypocalcaemia, so a radiographic assessment is advisable. |

| Uterine infections | Based on culture and sensitivity results. Pyometra may require surgery after fluid stabilisation. |

| Mastitis | Enrofloxacin and oxytetracyclines may be useful with NSAID analgesia. Surgery may be required if abscessation is severe. |

| Fractures | Spinal trauma has a poor prognosis, but methyl prednisolone may be used peracutely. Minor fractures may respond to cage rest and infood NSAIDs. Long bone fractures will require fixation preferably with external or tie-in fixators. |

| Seizures | Removal from rooms with TV and computer screens. Use of 0.5–1 mg/kg diazepam intramuscularly may help. |

Marsupial disease therapies

Tables 6.23 and 6.24 discuss common treatments for selected diseases of sugar gliders and Virginia opossums on a system basis.

Table 6.23 Treatment of selected skin, digestive and respiratory system diseases in sugar gliders and Virginia opossums.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Bacterial skin disease | Antimicrobials such as amoxicillin, cephalexin, enrofloxacin and TMP sulfonamides have all been used successfully against bacterial pyodermas in marsupials. |

| Fungal skin disease | See dermatophytosis in Table 6.12. |

| Parasitic skin disease | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg for mites. Pyrethrin powders have been used against other ectoparasites topically. |

| Dental disease | Extraction of rotten teeth, scaling and polishing and antibiosis with potentiated amoxicillin is recommended. |

| Gastroenteritis | Bacterial disease may be treated with amoxicillin or enrofloxacin. Nematodes may be managed with ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) or fenbendazole (20–50 mg/kg). Giardiasis has been treated with metronidazole. |

| Pneumonia | Bacterial pneumonia has been treated with fluoroquinolones such as enrofloxacin or penicillins. |

Table 6.24 Treatment of selected cardiovascular, urogenital, musculoskeletal and neurological diseases in sugar gliders and Virginia opossums.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Cardiomyopathy | Treatment is similar to that in ferrets |

| Heartworm | Treatment and prevention is similar to that in ferrets – again beware of anaphylactic shock when treating. |

| Urolithiasis | Catheterisation of the urethra in males to relieve any blockages. Flushing of the bladder or cystotomy to remove larger uroliths. |

| Metabolic bone disease | Correction of the diet to increase calcium and vitamin D3/provision of ultra violet light in early stages. Calcitonin has been used once blood levels have been normalised to encourage calcium deposition in the bones. In later stages, the problem is not reversible. |

| Paresis/paralysis | Common sequel to metabolic bone disease, particularly in sugar gliders and so may not be treatable. |

Mustelid disease therapies

Tables 6.25–6.28 discuss common treatments for diseases of mustelids (chiefly the domestic ferret) on a system basis.

Table 6.25 Treatment of selected skin diseases in mustelids.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Mites | Ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg once and repeated after 14 days. This author has found success in treating ear mites (Otodectes cynotis) using Advocate spot-on for small cats and ferrets® (Bayer Animal Health), although this product is not specifically licensed for this use in the United Kingdom. |

| Fleas | A licensed product containing imidacloprid and moxidectin (Advocate spot-on for small cats and ferrets®, Bayer Animal Health) exists in the United Kingdom for treating flea infestation and preventing heart worm disease (Dirofilaria immitis infection). |

| Bacterial disease | Based on culture and sensitivity with drugs such as enrofloxacin at 5–10 mg/kg (licensed UK product Baytril 2.5% oral solution®, Bayer Animal Health), potentiated sulphonamides at 15–30 mg/kg twice daily and potentiated amoxicillin at 10–20 mg/kg twice daily. |

| Dermatophytosis | See dermatophytosis in Table 6.12. |

| Neoplasia | Surgical excision where possible. |

| Hormonal skin disease | Testosterone or oestrogen-dependent alopecia – implantation with a gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (e.g. deslorelin (Suprelorin®, Virbac)). Neutering is no longer recommended due to the development of adrenal gland neoplasia and disease subsequently. Hyperadrenocorticism treatment is given in Table 6.28. |

Table 6.26 Treatment of selected digestive system diseases in mustelids.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Dental disease | Extraction of rotten teeth, antibiosis with clindamycin at 5.5 mg/kg twice daily or potentiated amoxicillin is recommended. Encourage dry foods to prevent recurrence. |

| Gastric ulceration | Remove any gastric foreign bodies as these can result in gastric ulceration. Use cytoprotectants: cimetidine (10 mg/kg twice daily), sucralfate (100 mg/kg daily orally) and bismuth subsalicylate (1 mL/kg three times daily, orally). If Helicobacter mustelae is present, combined amoxicillin and metronidazole is advised but enrofloxacin at 4.25 mg/kg q12 hours with bismuth subcitrate (6 mg/kg q12 hours) for 14 days has also been used successfully (Johnson-Delaney, 2009). |

| Proliferative ileitis | Chloramphenicol is the antibiotic of choice. |

| Lymphoma | Chemotherapy with drugs such as vincristine, cyclophosphamide and prednisolone has been tried but prognosis is guarded and depends on numerous factors including age, lymphoma grading and type. |

| Bacterial disease | This is based on culture and sensitivity results of faeces samples, but fluoroquinolones and potentiated amoxicillin are effective against a range of Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria. |

| Parasitic disease | Giardiasis treatment is with metronidazole. Coccidiosis is with sulfadimidine. Nematode infestations may be treated with 0.2 mg/kg ivermectin or with oral fenbendazole (various products licensed under the SAES). |

| Liver disease | Lactulose at 1.5–3 mg/kg orally once daily may help. Supportive therapy with vitamin B supplements and reduced fat/high biological value proteins advised. Use of inositol, L-carnitine and extract of milk thistle may also be useful where hepatic lipidosis is present. |

Table 6.27 Treatment of selected respiratory, cardiovascular and urinary system diseases in mustelids.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Canine distemper virus | There is no treatment. Prevention is by vaccination. No currently licensed ferret vaccine in the United Kingdom (although one exists in the USA). In the United Kingdom, canine distemper vaccines are used but care should be taken to choose a vaccine not raised in ferrets. Consultation with the canine vaccine manufacturer is advised for specific dosing. |

| Bacterial pneumonia | This is based on culture and sensitivity results, but fluoroquinolones and potentiated amoxicillin are effective against a wide range of Gram-negative and positive respiratory pathogens. |

| Congestive heart failure associated with dilated cardiomyopathy | Furosemide at 1–4 mg/kg in acute crisis is useful, intravenously or intramuscularly. ACE inhibitor enalapril at 0.5 mg/kg every 48 hours but watch for hypotensive effects. Pimobenden at 0.25 mg/kg q12 hours may be used as a positive inotrope. Digoxin may also be used in heart failure where atrial fibrillation occurs. |

| Lungworm and heartworm | These can be treated using avermectins such as ivermectin, selamectin or moxidectin. When treating cases of patent heartworm infection, massive die-offs of the nematode can result in anaphylaxis or vascular blockage. In ferrets, Advocate spot-on® (Bayer) has a license in the United Kingdom for preventing heartworm. |

| Urolithiasis | Surgery may be required to remove obstructions and/or bladder stones. Feeding an all-meat-based protein diet is essential to prevent formation. Treatment of any primary or secondary cystitis is based on culture and sensitivity results. |

| Chronic renal failure | This may be treated as in the domestic cat. |

Table 6.28 Treatment of selected endocrine, reproductive and ocular diseases in mustelids.

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Hyperadrenocorticism | Medical therapy can be ineffective as the tumour is adrenal based. However, recent work with gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonist (GnRH) deslorelin (Suprelorin®, Virbac) suggests that this implant may help in some cases to reduce tumour size and clinical effects. Otherwise treatment is surgical. |

| Insulinoma | Surgical excision of pancreatic neoplasm – but may be difficult due to their small size. Management with oral prednisolone (0.25–2 mg/kg q12 hours) with weekly monitoring of blood glucose levels. Diazoxide has been used where resistance to prednisolone is seen. |

| Diabetes mellitus | Tends to be rare but treatment is based on protamine zinc insulin at 1–2 units per ferret, and increasing by 0.5 units until blood glucose falls to 15 mmol/L or urine glucose to 0.5%. Twice daily dosing may be required. |

| Pregnancy toxaemia | 40% glucose at 0.5–1 mL/kg by slow intravenous bolus. Bicarbonate supplement to fluids is advised to counteract acidosis. Dexamethasone may be required in severe cases but abortion will occur. |

| Uterine infections | Surgical spaying after fluid stabilisation and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics until culture and sensitivity results are available. This may lead to adrenal gland neoplasia in later life. |

| Mastitis | Broad-spectrum antibiotics and NSAIDs with fluid therapy advised. Surgical excision of abscesses may be needed. |

| Hyperoestroginism | Prevention based on implantation of GnRH agonist deslorelin (Suprelorin®, Virbac) at 5 months, or mating with an entire or vasectomised hob, or regular proligesterone treatment at the start of the season (50 mg/jill). If disease has developed then treat with blood transfusion if PCV < 20%, or in early stages stop oestrus with proligesterone or human chorionic gonadotrophin and then use GnRH implant. |

References

Girling, S.J. (2003) Preliminary study into the possible use of benazepril on the management of renal disease in rabbits. British Veterinary Zoological Society Proceedings, Edinburgh Zoo, p. 44.

Harcourt-Brown, F.M. and Holloway, H.K.R. (2003) Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection in pet rabbits. Veterinary Record, 152, 427–431.

Johnson-Delaney, C. (2009) Ferrets: digestive system disorders. Manual of Rodents and Ferrets (eds A. Meredith & C. Johnson-Delaney), pp. 275–281. BSAVA, Quedgeley, UK.

Suter, C., Muller-Doblies, U.U., Hatt, J.M. and Deplazes, P. (2001) Prevention and treatment of Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection in rabbits with fenbendazole. Veterinary Record, 148, 478–480.

Further reading

Fraser, M.A. and Girling, S.J. (2009) Rabbit Medicine and Surgery for Veterinary Nurses. Blackwell-Wiley, Oxford.

Keeble, E. and Meredith, A. (2009) Manual of Rodents and Ferrets. BSAVA, Quedgeley, UK.

Meredith, A. and Johnson-Delaney, C. (2010) Manual of Exotic Pets, 5th edn. BSAVA, Quedgeley, UK.

Quesenberry, K.E. and Carpenter, J. (2003) Ferrets, Rabbits and Rodents, 2nd edn. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree